Improving housing mobility in Australia is crucial for enhancing both individual well-being and broader economic benefits. It can address challenges in housing affordability and ensure that people can move for personal, work, family or other reasons, while also improving long-term societal outcomes.

Housing mobility offers important economic advantages. It enables individuals to pursue better job opportunities, improving productivity. In addition, moving to a more suitable neighbourhood can have lasting positive effects on children’s education and overall quality of life. On the other hand, the lack of housing mobility can exacerbate housing affordability issues. When people are unable to move freely, it can result in mismatched living arrangements, where the number of residents in a home doesn’t align with the number of available bedrooms, thus reducing the overall supply of appropriate housing.

That said, not all housing mobility is desirable. Frequent moves can negatively impact renters, particularly when they are forced to relocate by their landlords. The direct costs of moving, along with the disruption of social networks, can undermine personal well-being. Moreover, frequent school changes for children can hinder their educational progress.

In Australia, the most significant driver of housing mobility is high turnover among private renters. Around one-third of Australian households are private renters, and they move about four times more often than owner-occupiers and more than twice as frequently as social housing tenants. Compared with 26 other OECD countries, Australian renters exhibit the highest mobility, with only Iceland recording higher rates of renter movement.

The primary factor behind this high level of mobility is the lack of security of tenure for private renters. More renters are forced to move by their landlords than move voluntarily for reasons like work or study, highlighting the need for reforms that provide greater stability and security in rental agreements.

Renting needs to be a more viable long-term option

In recent decades, Australian homeownership rates have declined, and young people today are less likely to own a home compared with older generations at a similar age. While the decline in homeownership isn’t inherently negative – since homeownership does not automatically equate to societal improvement and renting can often be a more attractive and flexible option – it does highlight that the rental market is not currently structured to support long-term tenancy in a way that benefits renters.

Currently, renting carries several drawbacks, such as restrictions on making minor alterations to properties and a lack of tenure security. This lack of stability creates unnecessary challenges for renters, affecting their sense of security and well-being. Research shows that stable and secure rental tenure can improve mental health. However, long-term leases are rare in Australia, and renters often live with constant uncertainty, unsure if or when they will be forced to move due to factors beyond their control, such as landlord terminations.

Improving rental security

One key reform to enhance rental stability is removing the landlord’s ability to evict tenants without due cause. Tenants should only be evicted for prescribed reasons, ensuring greater security of tenure. Currently, in some states, tenants can be evicted with as little as 30 days’ notice at the end of a fixed-term lease or through substantial rent increases. Although rent increases can be challenged, the process is often difficult, leaving tenants in a vulnerable position.

Policies aimed at regulating rent increases, while avoiding blanket rent controls that could distort the market, could also improve stability. For example, a solution could involve capping rent increases for existing tenants in line with local rent price indicators, allowing larger increases only when necessary to recoup renovation costs. This approach, similar to measures implemented in Germany, would maintain a connection to market rents while preventing significant disruption to renters and encouraging investment in property.

Fostering a stronger market for institutional investors

Another approach to improving tenancy security is fostering a stronger market for institutional investors. A shift from individual to institutional property ownership could reduce the frequency of evictions caused by personal circumstances of landlords – such as a landlord deciding to move into the property themselves. Institutional investors are also more likely to maintain properties at acceptable standards to protect their reputations and avoid negative publicity.

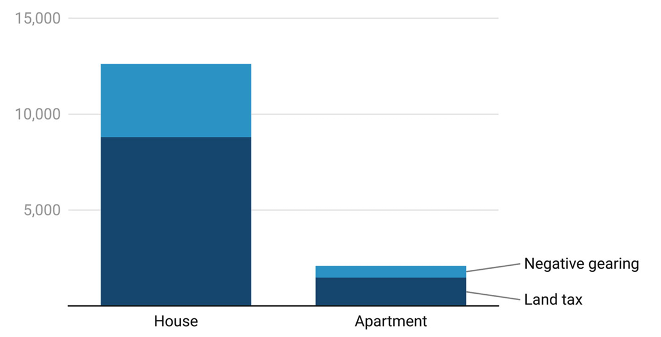

To encourage institutional investment, policies like build-to-rent schemes and addressing tax imbalances between individual and institutional investors should be prioritised. According to our calculations, an individual landlord who pays the 47% top marginal income tax rate can still enjoy tax advantages over an institutional investor due to negative gearing and the progressive nature of land tax, which favours holders of fewer properties (Figure 1). This tax advantage increases demand from individual investors, pushing up prices and reducing yields for institutional investors.

Figure 1: Annual financial advantage to an individual landlord over an institutional investor

Note: Based on data for Sydney, as described in Barker and Korczak-Krzeczowski (2024).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from CoreLogic, SQM Research, and the NSW Valuer General.

Existing policies reduce housing mobility among homeowners

Several existing policies in Australia contribute to reduced housing mobility, particularly among homeowners. One of the most significant factors is stamp duty, a transaction tax levied as a percentage of the purchase price of real estate. Stamp duty has been shown to discourage people from moving, as it represents a substantial financial barrier. In the United Kingdom, surveys have indicated that stamp duty is one of the top reasons people hesitate to downsize, making it a key factor in housing mobility decisions.

Another policy that limits housing mobility is the exclusion of the family home from the asset test for eligibility for the Age Pension. This exclusion creates an incentive for retirees to remain in their larger homes to preserve their wealth and retain access to the pension, rather than downsizing to more suitable properties. As a result, older Australians often hold onto homes that are no longer necessary for their needs.

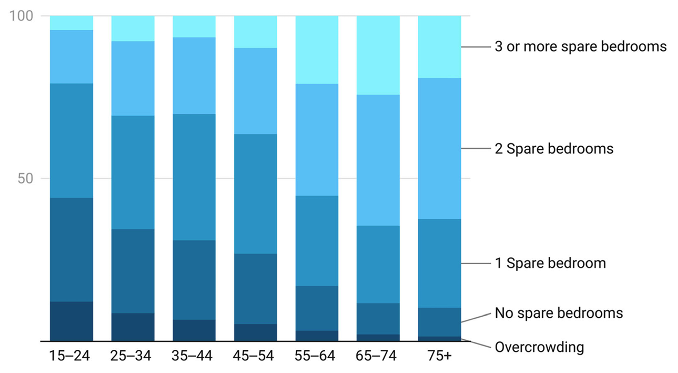

In fact, older households typically have more spare bedrooms (Figure 2), indicating that many have homes that are larger than required. As children move out or after the death of a spouse, these households often face a reduced need for the space. However, the combination of stamp duty and the asset test creates friction that discourages downsizing, leading to underutilised housing. This mismatch between housing needs and housing supply is a key issue for both individual homeowners and the broader housing market.

Figure 2: Housing utilization for different age groups

Source: ABS 2021 Census of population and housing

According to our recent research investigating the distortive effects of the asset test, we found that individuals receiving Age Pension payments are statistically significantly less likely to have moved in the past year compared to those who do not receive the payment. Additionally, we discovered that receiving the Age Pension is correlated with a lower rate of both house moves and financial downsizing within five years of starting Age Pension payments.

Policy discussion

In this article, we have highlighted the importance of policy changes to reduce barriers to housing mobility. Enhancing housing mobility not only improves individual’s quality of life but also supports labour mobility, which in turn can boost productivity across the economy.

For renters, ensuring greater security of tenure is crucial. It helps prevent costly evictions and supports more beneficial mobility by making renting a viable long-term option. Policies that support the availability of longer-term leases and remove landlords’ ability to evict tenants without due cause will create a more stable rental market. Moreover, lowering barriers to institutional investment in the rental housing market would help reduce evictions driven by personal circumstances of landlords. To complement these measures and prevent evictions through unreasonable rent hikes, we recommend using simple, locally calibrated metrics to cap rent increases for existing tenants. International evidence suggests that such an approach can avoid the negative impacts on rental housing investment often seen with more stringent rent controls.

For owner-occupiers, the barriers to housing mobility are contributing to a mismatch in housing needs. As people age, it’s common for them to have more spare rooms, which, while sometimes a personal choice, is often influenced by policies that discourage downsizing. Stamp duty and the exclusion of the family home from the Age Pension asset test are key factors in this trend. These policies should be reviewed, as they discourage retirees from downsizing, leading to the inefficient use of housing space and contributing to housing affordability issues.

Citation:

Barker, Andrew & Korczak-Krzeczowski, Aaron, (2025), Reforms to Improve Housing Mobility in Australia, Austaxpolicy: Tax and Transfer Policy Blog, 16 February 2025, Available from: https://www.austaxpolicy.com/reforms-to-improve-housing-mobility-in-australia/

Andrew Barker is Head of Research at CEDA, where he has led economic research on the energy transition, labour markets, housing and migration. Aaron Korczak-Krzeczowski is an economist at the Productivity Commission, contributing to research and policy analysis on economic and social issues for the Australian Government.