In the 1987 film Wall Street, Gordon Gekko is challenged by his prodigy, Bud Fox, on how much money is enough. Gekko responds that it’s not a question of enough - it's a zero sum game. Money itself isn't lost or made, it's simply transferred. Somebody wins, somebody loses.

Significant new research soon to be published in the Journal of Portfolio Management* reveals a win lose dynamic in mutual fund investing (what we call ‘managed funds’ in Australia). The key finding is the average United States mutual fund retail investor underperforms the fund they invest in by about 2% a year. While the fund’s investment strategy may be sound and generating outperformance against a benchmark, investors’ poor timing of when they buy in and sell out effectively transfers elsewhere the value premium created by the fund.

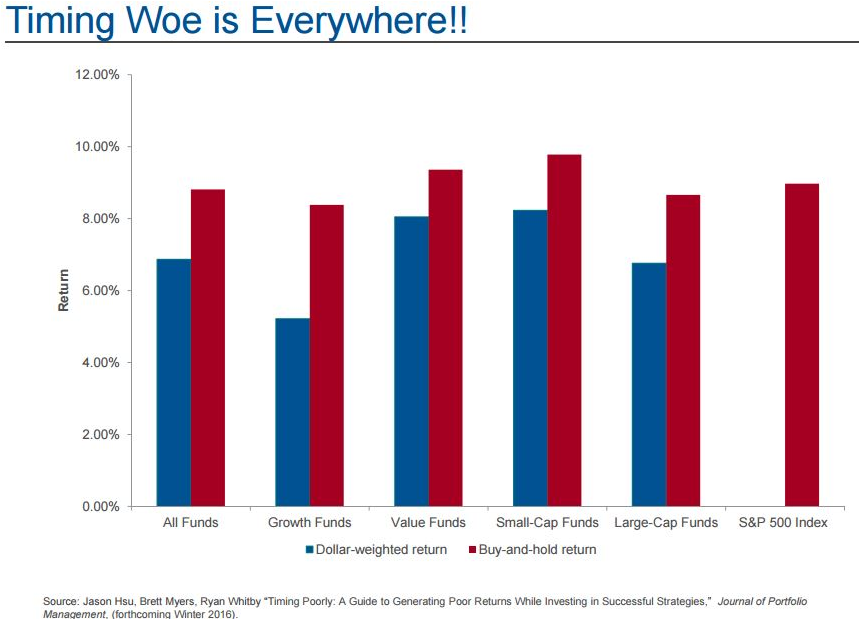

In reaching this finding the researchers analysed over 1 million fund flow observations across 18,665 funds between 1991 and 2013. The dollar-weighted average of investors’ returns within a fund was compared to the buy and hold return for the whole fund.

As the researchers explain:

“The average return from a buy and hold implementation ignores the fact that many investors trade on a regular basis and that the actual return received by the average investor might be very different from the buy-and-hold return. Dollar weighted returns account for this trading by augmenting the average with information about fund flows.”

The pattern of average investors’ underperformance against overall fund performance was consistent across funds irrespective of varying investment styles – value, growth, large and small cap, as shown below:

The less sophisticated are worst at timing

Investors mistiming the market are underperforming by an average 1.3% to 3.1%, with worse investor underperformance seen in growth compared to value funds, and in large cap compared to small cap funds. For example, fund investors seem to time poorly by investing in value funds when the ‘value’ factor is expensive, and redeeming from value funds when ‘value’ offers opportunities. Poor timing is not confined to value funds, and confirms other studies which show investors attempt to time their allocations to funds.

The research reveals what is happening, but it isn’t possible to definitively conclude from the data why investors time poorly, and nor was this a stated purpose of the research. What is especially interesting is that it examines the actual investment outcome for mutual fund investors, not the performance of mutual fund managers.

The data leads to an hypothesis that investors who time poorly are less financially sophisticated. This is deduced from more detailed multivariate analysis revealing the worst average returns were seen by investors who hold funds with higher expense ratios, and who invest in readily available retail-oriented mutual funds. Investors in these funds were observed as more likely to time poorly, buying after and selling before periods of strong performance.

Their poor timing may be unintended – for example investors may withdraw to meet unexpected financial needs. It may be related to low financial literacy. They don’t understand their investment timeframe isn’t suited to the fund’s recommended timeframe. Or it may be from overestimating their investing prowess. They are consciously trying to time outperformance or chasing previous hot performance by the fund. Whatever the reason, they have timed poorly and are Gekko’s losers. In fact, the authors subtitle their paper, “A Guide to Generating Poor Returns While Investing in Successful Strategies.”

Value premium is transferred to the winners

So who are the winners on the other side of the trade? The research is based on United States data where mutual funds account for nearly 20% of the equity market. The authors suggest institutional investors are most likely to be capturing the return premium from retail fund investors: smarter traders adhering to more considered strategies. By giving away the excess return, retail investors in value funds might themselves be financing the value premium often seen in fund performance, and ensuring its continuance.

What might be done about it? After all, retail mutual fund Product Disclosure Statements are filled with recommended investment timeframes, likelihoods of negative returns over given time periods, explanations of different investment risks, statements that past performance is no indication of future performance and the importance of time in the market as distinct from timing. What is missing that will grab investors’ attention and help them avoid poor timing?

Investors may reconsider their own behaviour if presented with the hard real dollar impacts of poor timing experienced by others. Perhaps fund providers could undertake similar analysis on observations within their own funds and present key findings to investors and financial advisers (assuming of course empirically the same pattern holds). It points to a need for greater financial education to protect investors from themselves.

Without behaviour change poor timing will continue and many investors will miss the returns their mutual funds generate. They lose and somebody else wins.

*Jason Hsu, Brett Myers, Ryan Whitby, “Timing Poorly: A Guide to Generating Poor Returns While Investing in Successful Strategies”, Journal of Portfolio Management (forthcoming Winter 2016).

Iain Middlemiss was Executive Manager Strategy at Colonial First State and Head of Strategy at Superpartners. This article is for general educational purposes only.