And so, what can we expect of the balance of the 2020s beyond the coronavirus?

It is likely for example that there will be greater use of technology and a lesser engagement with China. It is also possible that the community will take a renewed interest in hand washing, in appreciating family, in having the freedom to travel beyond Australia. These ‘reactions’ to events triggered by the pandemic are logical enough, I suppose, but there is something else sitting out there, lurking (with intent) in the middle of the decade.

Baby boom must lead to a baby bust

It is something demographers have known about for decades. Indeed, there have been books written (by demographers) about its impact. This menace goes by the name of the baby bust. If you accept there was a baby boom in the 1950s then 70 years later the limitations of human life dictate that there will be, there must be, a baby bust.

In a crude sense, the baby bust takes effect when baby boomers press into their 70s and – how shall I put this? – then they die off. But the baby bust is more than this. It will trigger workforce and funding issues that will need to be managed. More baby boomers aged 65 exiting the workforce than 15-year-olds entering the workforce leads to a diminution of workers and, some would say, also of taxpayers.

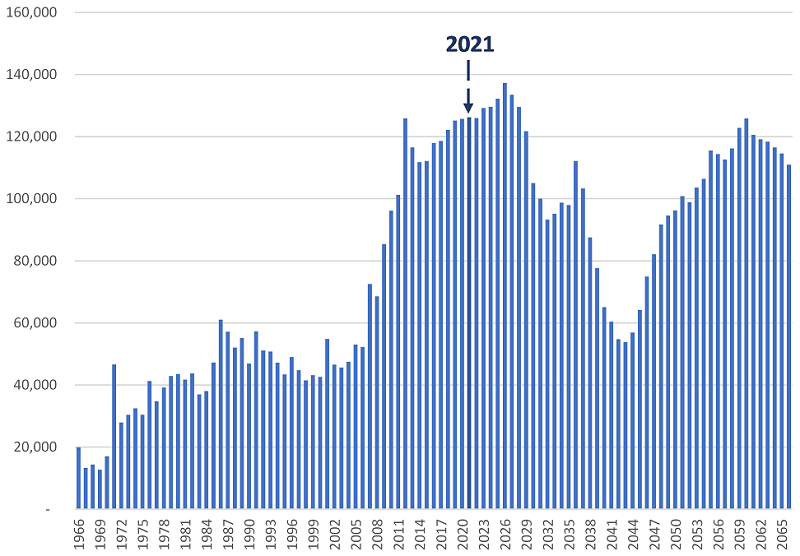

The number of people entering the so-called ‘retirement age’ of 65+ has ramped up over time. In the 1990s, for example, Australia’s 65-and-over population increased by an average of around 40,000 per year (see graphic). Retirees in this decade were born in the 1920s.

Boomer’s retirement mountain: net annual change in Australian population 65+, 1966-2066

Data source: ABS Historic, Estimated and Projected population

But 30 years later in the 2020s it’s a different story. The number of Australians being added to the 65+ cohort every year will rise during this post-pandemic decade passing 126,000 in 2021, peaking at 137,000 in 2026, before subsiding to 105,000 in 2030. This surge in the retiree population is caused, of course, by the great baby boom of the 1950s.

Impact of surge into retirement towards five million

The transitioning of the baby boom population from working age to retirement stage will ‘play out’ in the post-covid 2020s. The retirement cohort will continue to expand for another five years creating a community culture that is hyper-sensitive to retirement issues.

It could be argued that the social impact of ‘retired Australians’, based on underlying demography, will not begin to subside until later in the decade.

In this context the period 2021-2027 will represent the peak years of the Australian baby-boom retirement surge. Not only is this an issue of the retirement cohort’s collective voice (now close to five million) but this will also translate into an elevation of retirement issues such as concerns about health care and aged care and access to various aged-based financial concessions.

Perhaps there will be a new political movement based around ageism?

Baby boomers will be the first generation of retirees who will have memory of their parents in retirement. Previous generations of retirees had no real experience with long-term ageing because, well, their parents died in their 60s. The parents of baby boomers lived on and into their 80s and 90s and there’s a photographic record of their time in retirement.

Baby boomers will not age as past generations did

Baby boomers in retirement, peaking in the middle of the 2020s, but extending in progressively fewer numbers into the 2030s and 2040s, will be determined not to age as their parents aged. They are already railing against ageism. Many are remaining in the workforce. Some are re-partnering later in life. Some are choosing to remain single (but not lonely) in life’s later years.

The concept of a large proportion of the population living beyond the age of 65, being dependent upon the goodwill of younger cohorts, and the reliability of governments to uphold the social contract implicit in the idea of 'ageing with dignity' are all new to humanity.

What to do with the aged wasn’t a problem for previous generations in history.

It could be argued that the 2020s really is a turning point and not just because of the new world that is likely to emerge from the post-pandemic ashes, but because of the longevity of life for perhaps one-fifth or one-sixth of the Australian population.

Mistakes will be made by governments and retirees. However, what will be required throughout the decade ahead is goodwill on both sides. And an appreciation that no society in history has been placed in the position of having to care for such a large proportion of its population in the older age groups.

The next generation of retiree will be fitter and lither than previous generations. Baby boomers are interested in wellness; they stopped smoking decades ago; they watch what they drink. Some will want to work on, not wishing to be a burden, but they’ll also want to work on for the purpose of leaving a legacy of sorts.

The old idea of retirees wafting off into the abyss of retirement might have worked for the pre-boomer generation. It will not work for boomers.

They are well educated and they have time on their hands

The next generation of retirees will also include a large proportion who had access to (fee-free) tertiary education in the 1970s. And so, the 2020s will deliver the first generation of retirees who will be tertiary educated, opinionated, articulate, computer-literate and with time on their hands.

Could I suggest that this is a dangerous combination for politicians, bureaucrats and business leaders who will have to deal with an increasingly galvanised and vocal retiree population?

The 2020s will present a number of challenges for an Australia struggling to recover from the devastation of the coronavirus impact and its associated lockdowns.

However, as difficult as this recovery process may be, and especially if it coincides with geopolitical challenges for this part of the world, there is some comfort to be taken in the knowledge that these (baby bust) issues will also surface in other developed nations like America, Great Britain, Canada and especially Japan.

It may take some time and there may be some missteps along the way. But I have confidence that eventually the inherent prosperity and goodwill of the Australian people will prevail and deliver a society that is indeed fair to and caring of the baby bust cohort as they gingerly make their way through life’s later years.

Bernard Salt is executive director of The Demographics Group. Baby bust graphic published in the ASFA white paper February 2021, reproduced with permission.