The more I write about retirement, the more I learn. And the more aware I become of what seems to be an alternate reality or parallel universe when it comes to how much money Australian retirees will actually need.

On the one side is the rather chirpy spin which paints a vision of an ideal retirement, presumably available to most, underpinned by secure funding for life.

Who wouldn’t want that?

And then on the other side of the divide is a much messier affair, fraught with doubt and concerns and the ever-present FORO – the fear of running out.

The ‘securely funded’ camp tends to assume that everyone agrees that the regularly updated Cost of Living in retirement tables offer reliable targets for ‘most’ retirees. But that is a stretch at best. And potentially dangerous at worst.

The problems with retirement spending targets

This too-easy acceptance of retirement spending targets troubles me greatly.

Here’s why I believe the cost-of-living assumptions and generalisations are reducing the ability of ordinary retirees to fully understand their retirement income options.

Let’s start with one of the ‘sunny-side up’ indices – the ASFA Retirement Standard.

It’s been around for decades and is continually quoted as the ‘rolled gold’ standard. As such, it is rarely questioned. But it should be. Many industry insiders are in agreement that these numbers are unrealistic. There are two key problems with them, which are widely recognised, but rarely challenged. The standard offers targets for those aged 65-84 and 85+. Let’s limit this discussion to the amount needed for 65-84-year-olds.

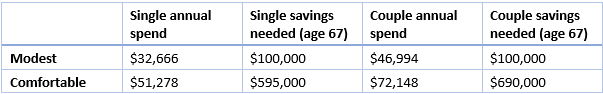

The current ASFA amounts (published March 2024) are:

The modest lifestyle targets are more than modest, they are frugal. They do not allow for emergencies or expensive health care. There is another assumption, and that is that an Age Pension will be available to all above categories.

Separate to the Retirement Standard, ASFA publishes regular updates on the super account levels for various ages. [Most recently, An update on superannuation account balances November 2023]. Eschewing the average amounts as they can be skewed by a handful of people with very high balances (one unnamed soul has more than $500 million in his/her account!), the mean amounts tell us quite a lot.

For those in early retirement, aged 65-70, the median amount is $213,986 for males and $201,233 for females. If we add these amounts together for couples ($415,000) we can see that at least half Australian retirees will struggle currently to have anywhere near the $690,000 for couples or $595,000 for singles deemed necessary for ‘comfortable’ by ASFA.

The savings targets for modest lifestyles of $100,000 (both single and couple) also carry the assumption that all retirees own their own home with no debt, that they will receive a part-Age Pension and that they will spend all their capital.

There are a few problems here.

Firstly if more than half Australians (i.e. the median) have a super balance which, for couples is 415/690 or barely 60% of that needed for this comfortable goal, maybe comfortable is actually more accurately described as affluent?

It’s worse for singles, with say $207,000 the median balance (for males or females) which is 207/595 means just 37% have the amount required to be ‘comfortable’.

In plain language, most Australians will NOT be anywhere near ‘comfortable’ based upon these numbers which are called a ‘standard’.

The second problem and perhaps the more important one is the assumption of home ownership. Only 82% of retirees owned their own home, according to the Retirement Income Review, 2020). This will now have decreased even further. So there are a group of retirees who are simply not taken into account with these calculations – the ‘others’ – the renters and those who live with family. Where is the standard for them?

And then of course we have a third problem; the real elephant in the room. Homeownership is automatically assuming no mortgage. How far out of date is this notion? Recent research from Professor Rachel ViforJ indicates that more than 50% of homeowners aged 55 and over have a mortgage. Many may expect to reduce this or pay it off when they reach preservation age. But that will only further reduce their super so that the median savings amount quoted above may actually decrease, rather than increase. Yes, the Super Guarantee will increase to 11.5% on July 1 this year, but that is not going to solve the problem of a $50,000, $100,000 or higher mortgage debt.

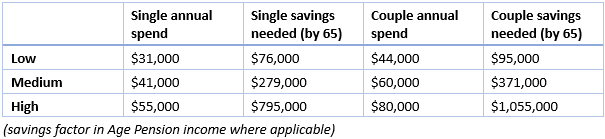

More recently, advocacy group Super Consumers Australia (SCA) decided to publish targets that it believed to be more realistic than the ASFA targets. Here are the SCA spending and super balance goals for current retirees (aged 65-69):

Yes, there are three levels in these targets, rather than two, which offer more nuance.

But guess what? Yes. Again, the assumption has been made that all retirees live in a home they fully own.

Why aren't mortgages factored in?

Now of course the smart brains at ASFA and SCA will know the degree of indebtedness of Australian retirees as much as anyone else. So why do they not factor a mortgage into the suggested cost of living in retirement tables? Is it too difficult to do so?

This was the question I asked Ross Clare, Director of Research, at ASFA and Xavier O'Halloran, Founding Director at SCA.

The ‘short’ answer from both organisations was that it is difficult to allow for very different levels of retiree indebtedness.

Xavier O'Halloran said it was something that SCA had considered addressing, but they felt a broad rule of thumb would be for retirees to look at suggested savings targets and add on the amount of the mortgage, so that individuals could better understand their income prospects. This simple calculation doesn’t of course allow for interest on repayments, as O'Halloran acknowledged. He did suggest, however, that using the Moneysmart calculators would be useful for those with mortgages.

ASFA responded with a statement attributed to CEO, Mary Delahunty, which said:

“The ASFA Retirement Standard budgets focus on the housing status relevant to the great bulk of current Australian retirees and those approaching retirement.

Unlike other housing costs which continue throughout retirement, mortgage payments are highly variable, depending on both the amount still outstanding on the mortgage and the remaining term of the mortgage. For most individuals aged 65 plus who still have a mortgage, repayments are typically at a modest level.

A better approach for those approaching retirement who still have a mortgage is to add the mortgage balance to the required lump sum for outright homeowners and to compare that with their superannuation and other retirement savings and/or to have an exit strategy involving downsizing or the like.”

ASFA also shared a table showing low numbers of homeowners aged 65+ with a mortgage. But as we have seen, the trend is for this ratio to change, rapidly.

Greater scrutiny of retirement targets needed

Which takes us back to the starting question, ‘How useful are these retirement savings and spending targets in the real world?’

Not very, I suspect.

And why do financial journalists continue to report such standards as the norm?

I guess it’s because no one can be bothered to do the hard yards and come up with something more useful. Which means the growing number of retirees who need support to manage mortgages will continue to go under the radar – and remain highly stressed about how they will cope.

Kaye Fallick is Founder of STAYINGconnected website and SuperConnected enews. She has been a commentator on retirement income and ageing demographics since 1999. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any person.