Last year in Cuffelinks, I wrote an article entitled ‘Fear of missing out trumping fear of loss’ in which I highlighted the overwhelming demand for Argentina’s 100 year bond issue, despite the country’s litany of defaults, military coups, and bouts of hyperinflation over the last 90 years. The demand for Argentina’s bond issue was the tip of an iceberg representing investors’ insatiable appetite for returns above cash.

'Fear of missing out' driving markets

From post-80s American art, to low-digit number plates, stamps, coins, wine, and collectible motor vehicles, 2017 saw auction records smashed just as the appetite for Bitcoin, KodakCoin, and any company that added Blockchain or Nodechain to their name, fuelled a fear of missing out that usurped the fear of loss.

Then last month I wrote; “I do not know with any useful accuracy when the US market will turn down more meaningfully than it did last week …”, and I listed many problems facing markets.

The recent enthusiasm for higher return and higher risk alternatives, which always defines the late stages of a boom, has begun unwinding. And the unwinding will have serious implications for equities, especially those companies whose earnings multiples can only be supported by an uninterrupted period of high growth rarely achieved in the business world.

One useful signpost, following a period of unbridled optimism, that an unwinding has begun, is investors in credit markets pulling back, even while equity investors continue to party.

First, let's look at equities

In late January and early February, volatility spiked but investor bullishness and complacency were largely unwavering, especially when it came to tech stocks – enthusiasm for which was reflected in new March highs in the Nasdaq.

One of the most crowded trades has been US technology stocks. Today the Nasdaq 100 is dominated by a few names as investors have piled into index funds that care little about future prospects or value. Apple (NASDAQ: APPL) alone accounts for 12% of the Nasdaq 100 index. Alphabet (NASDAQ: GOOGL) at 9.4%, Microsoft (NASDAQ: MSFT) at 8.2%, Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN) at 6.9% and Facebook (NASDAQ: FB) at 5.5% are the next four largest companies. A significant part of the gain in both the Nasdaq 100 and the S&P 500 indices over the last year can be attributed to an extremely narrow band of tech stocks.

Immovable bullish sentiment toward a narrow band of similar companies is reminiscent of the heavily-crowded positioning that has marked important market tops of the past.

In the week ending 23 March 2018, investors poured $3.3 billion into the PowerShares QQQ Trust Series 1, the biggest exchange-traded fund tracking the Nasdaq 100 index. It was a cash injection into technology shares not seen since the peak of the tech bubble. J.P. Morgan also reported the biggest weekly inflow ever into equity ETFs in the week ending 16 March of US$34 billion.

Now to credit markets

Meanwhile, US corporate bonds are sending investors a warning. Investment grade bond spreads now sit near their widest level in six months and yields have risen to their highest level in six years. Corporate bond investors are pushing yields higher, signalling the greater risk associated with investing, while their equity counterparts continue to accept a high P/E and prices that imply ultra-long-term growth rates that few businesses have ever achieved.

Elsewhere, current forecasts for US federal government borrowing needs, expected to exceed 100% of GDP by 2028, are brushed aside. By contrast, we have been reminded of the 1980s, when federal publicly-held debt hitting nearly 40% triggered fears of an apocalypse. According to some analysts the demographics were more favourable in the 1980s, and tailwinds existed in the form of productivity growth, financial-sector deregulation, and benign inflation. Today, these could now be headwinds and yet complacency over rising debt and deficits persists.

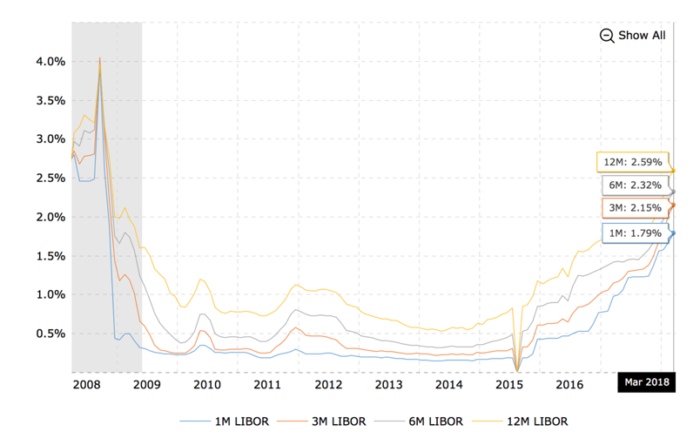

We agree with analysts who suggest the jump in the TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities) market and in Libor spreads to levels last seen in the GFC should be setting off alarm bells because it is a sign that monetary policy has tightened considerably.

LIBOR rates since 2008

Quantitative Easing has been inflationary for property and financial assets including equities, bonds and bond proxies. Quantitative Tapering will at least generate heightened volatility in the same markets. And as volatility increases, cost-of-capital assumptions increase, opportunity costs rise, price-earnings multiples contract and credit stress or merely fears of credit stress become more frequent.

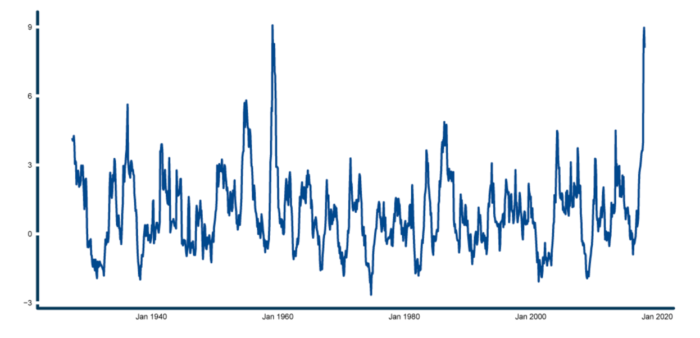

The 12-month annualised Sharpe Ratio for the S&P 500 reveals that the combination of very high returns and very low volatility in recent times is an anomaly last observed in the 1950s. The combination of higher volatility and lower returns is likely to return.

12-month annualised S&P 500 Sharpe Ratio to Dec.31, 2017

Source: Gestaltu, ReSolve Asset Management

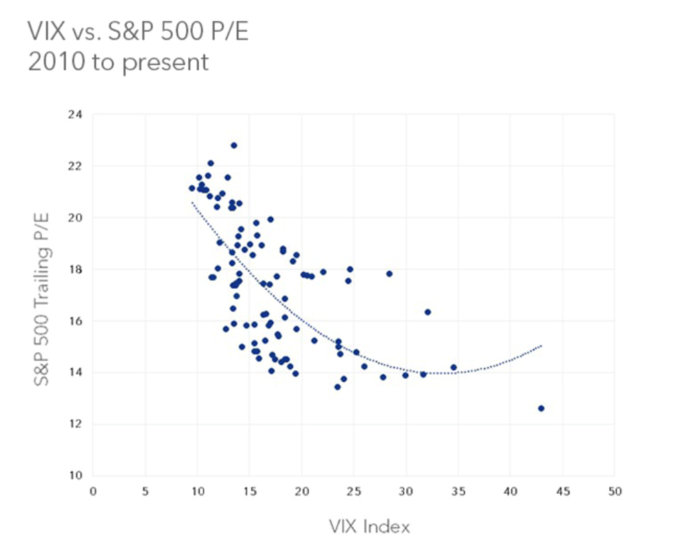

The figure below shows that when volatility (risk) as measured by the VIX index, picks up, P/Es (price to earnings multiples) contract. Investors are simply less willing to make optimistic assumptions about a company’s prospects, and therefore less willing to pay higher multiples, when a fear of loss replaces the fear of missing out.

Volatility as measured by the VIX Index versus P/E ratios for S&P 500

Source: Bloomberg, ETF Daily News

There are of course many arguments that suggest portfolios should be fully invested. We agree that in the long run, being fully invested is preferred. But it is also true that the higher the price you pay the lower your return, and holding long-term just means locking in a low return on a long-duration asset.

Prices today are factoring in all of the bullish arguments with little room for setbacks, hiccups, or speed bumps. In the bond market, some investors are already leaving. Those who are patient will be well rewarded for making additional investments only when there is blood in the streets.

Roger Montgomery is Chairman and Chief Investment Officer at Montgomery Investment Management. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.