Just as we believe both cyclical and secular inflection points are appearing on the horizon, market commentary is again reaching a climax in its declaration of the death of value investing. Compare the 1999 commentary on Warren Buffett to that of 2020:

“After more than 30 years of unrivalled investment success, Warren Buffett may be losing his magic touch.” - Wall St Journal, 27/12/1999

“…the worst results in Berkshire’s history underscore just how challenging the environment has been for [Warren Buffet’s] approach to picking stocks.” - Financial Times, 14/5/2020

Value continues to struggle

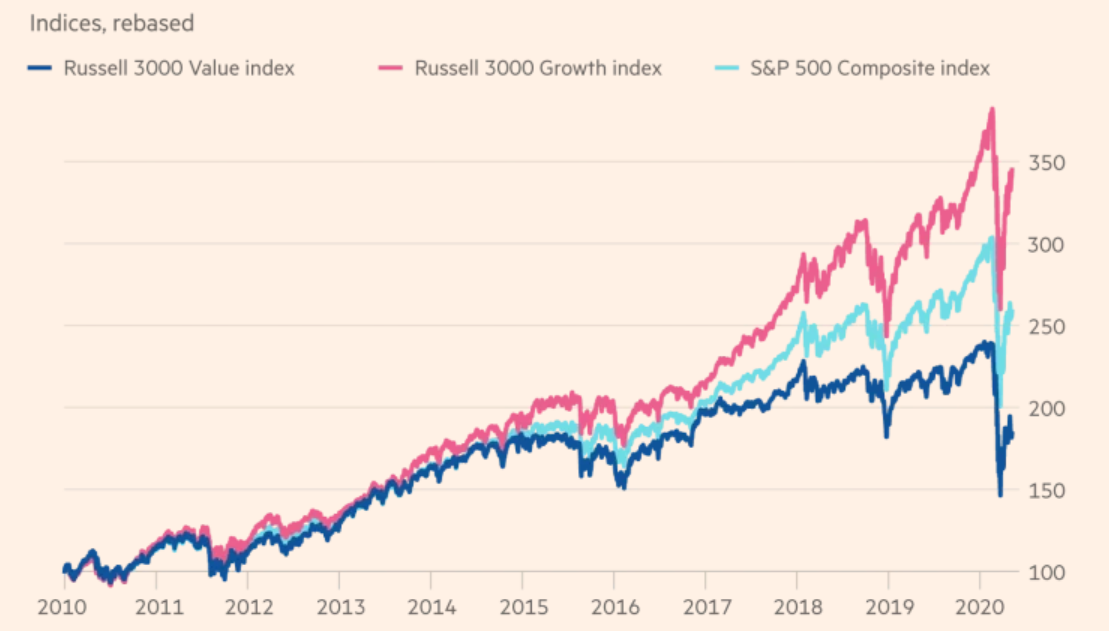

‘Value investing’ (defined as buying stocks that appear to be trading for less than their intrinsic value) has had a difficult run since the GFC. ‘Value’ stocks outperformed ‘growth’ stocks for a short time at the beginning of the 2010s, immediately subsequent to the GFC, but since then growth stocks have outperformed significantly.

Particularly from 2016 onwards, valuation has taken a back seat to the search for growth, and this has had a serious effect on what is known as value investing.

Source: FT

The Russell 3000 Value index (a broad measure of US value stocks) at the time of writing is down more than 20% in 2020 and since 2010 has risen 80%. On the other side of the ledger, the Russell 3000 Growth Index is up more than 240% for the decade and has bounced harder than value stocks in the post-March recovery.

In a benchmark like the S&P500, which is more concentrated and has larger stocks, the difference between value and growth has been even more pronounced. In the past decade the S&P500 Value Index has risen 82.0%. The S&P500 Growth Index over same period has risen 223.1%, heavily influenced by investors’ preference for the FAANGM tech stock complex (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Google and Microsoft), which accordingly now accounts for 25% of the S&P500 index compared to less than 9% in 2012.

The question remains - has there been a structural, permanent, change that will continue to favour large, growth-oriented stocks where raw valuation takes a second position, or can valuation still be a major part of the process and therefore value investing offer the potential for outperformance?

The impact of low rates

The largest factor to favour growth stocks is the historically low level of interest rates, quite possibly the lowest in 5000 years. As the level of rates has fallen, the cost of capital has fallen with it. Unlike previous cycles, the past decade has seen reserve banks around the world embark on yield curve control, otherwise known as quantitative easing, by flooding the market with liquidity and lower short-term rates. This has resulted in a wall of capital chasing the prospect of higher long-term returns offered by any company that investors perceive as having strong and consistent long-term growth potential.

Investor willingness to pay for and believe in strong or defensive long-term growth has been assisted by globalisation and the lack of national ‘virtual’ barriers (as opposed to physical national borders), benefitting large global-sized entities such as the FAANGM stocks. They, in their turn, have also benefited from technological improvements that have made the ability to order goods and services online seamless, as well as delivering advertising dollars. Their advertising capability is now to the point where the only media that can challenge the behemoths of Google and Facebook is free-to-air television advertising, and even that is now under attack from the likes of Google’s ‘in-clip’ direct response ads on YouTube.

While growth companies like Google and Visa have justifiably higher PE ratios given their growth trajectory, companies like Kimberly Clark that are perceived as defensive growth companies have also been bid up. This kind of stock would have traditionally been seen as more of a value play, but even its share price in the period 2009-18 rose 87%, while its operating income was flat (0% growth per annum).

The popularity of market capital-weighted index funds has also accentuated the growth of these large growth stocks, as seen in the performance of the Russell Value Index versus the S&P500 equivalent. The index funds have accentuated the moves of the big stocks, making them more resilient to what have been, on the surface, significant increases in valuations (noting, however, that active managers have not done themselves any favours in this regard. Scared of being left behind in their peer ranking tables, many have jumped on the bandwagon notwithstanding valuations).

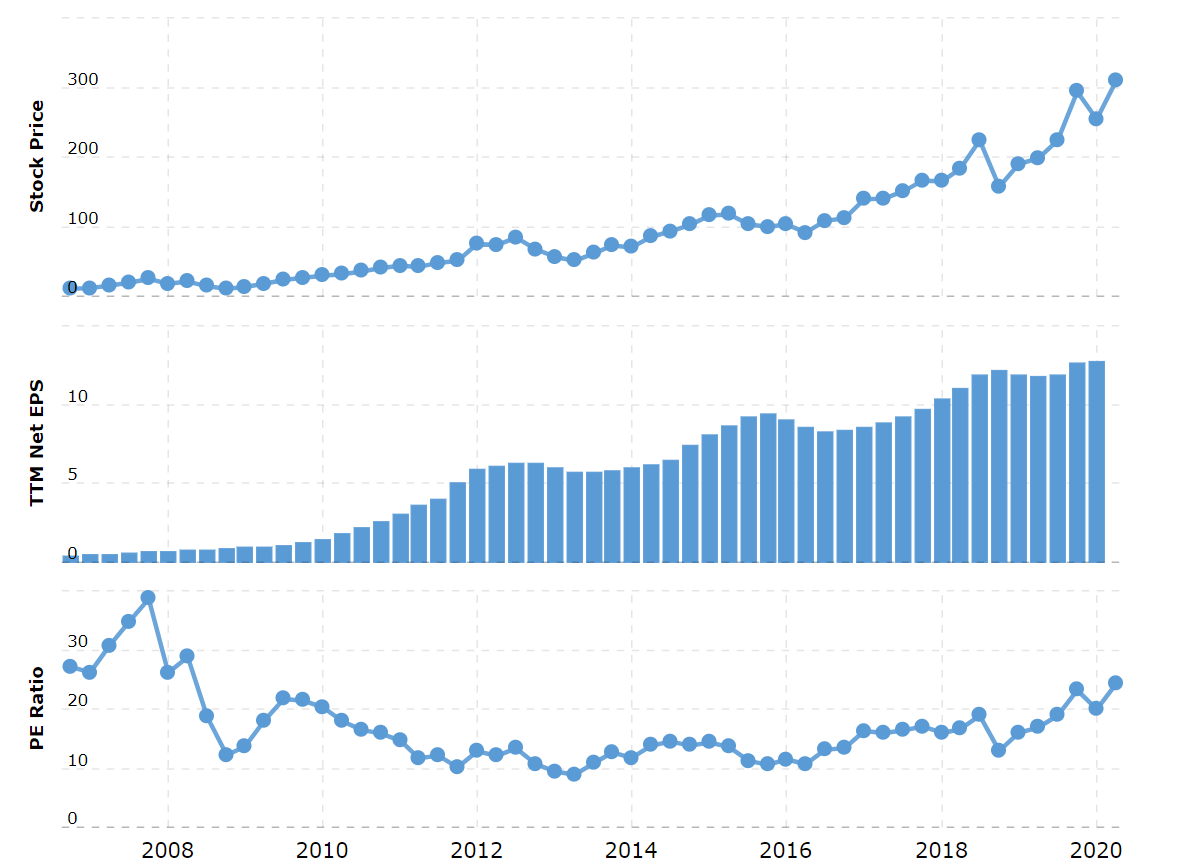

Apple also highlights the expansion in PE ratios. In the post-GFC environment its stock has moved from ~US$10/share (2008) to now be trading at over US$300 at the time of writing. Its earnings per share have risen also in that time, but nowhere near to the same extent. The market has moved to pay over 23 times historical earnings, whereas in 2016 it was closer to 10 times.

APPLE

Source: macrotrends.net

However, where can interest rates go from here? Bond yields are already at or below zero in many parts of the world. Implied yields on futures contracts linked to the federal funds rate have gone below zero, suggesting investors are betting that the Fed will cut its key rate below that by mid-2021, but the Fed’s chairman, Jerome Powell, has said that negative rates are not an “appropriate policy response”.

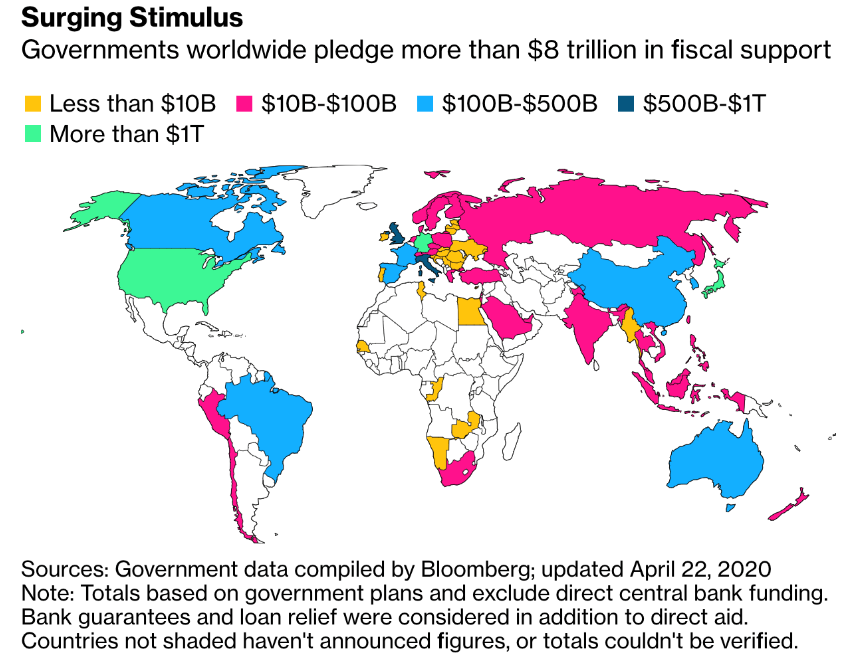

US$8 trillion of stimulus and counting

Fiscal stimulus to fight coronavirus is also at levels never seen before. Bloomberg estimates that over $8 trillion has and will be spent in a very short space of time globally propping up economies using a range of measures, including direct spending and bank guarantees.

How are we going to pay for all the fiscal stimulus? After the coronavirus has been tamed, taxes are going to go up but I doubt anyone has the stomach for real austerity. The reality is that apart from default, the only palatable option to deal with how we pay for the fiscal stimulus is inflation.

However, once the inflation genie is out of the bottle, if it pushes through reserve bank target levels, interest rates will be forced higher, resulting in at least a partial unwinding of the positive effects that lower interest rates have had on growth stocks over the past five years (in particular).

This is why I have been very strong in arguing that when we look out over the longer term, investors need to be thinking about businesses that will not be hurt by the evolution of inflation. This argument has obviously been affected by coronavirus, but my longer-term belief remains intact.

Everyone is jumping aboard the rally — for now

In December we saw European countries begin to understand that negative rates were not assisting economic growth, the US economy move into a stronger growth phase and signs of a rotation towards value stocks. In our portfolio’s case, banks, resources companies and stocks on low valuations such as Siemens moved forward strongly — gains that were carried into January 2020.

Of course, this was pre-coronavirus, which stopped this trend dead and re-ignited the search for any kind of semi-reliable growth by anyone that feels overall expansion will be moribund in the next 12 months.

The market is always ‘right’ — at that particular point in time. We can only go from where we are now. What is going to be key is the ability to ignore the crowd and the hot stocks because at the moment the market is like a yacht listing to one side. Everyone has clambered on, and, for the moment, it continues to sail, but at some point the yacht will right itself.

It is just a matter of time.

What is clear to me is that when you look at valuation, it would appear to be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity in quality cyclical and industrial stocks with the upside return possibility equal to or greater than what I saw post-GFC with the market in general.

We feel the pandemic has not simply delayed our thesis, but the fiscal and monetary actions will have the effect of essentially making the thesis inevitable. The unknown factor is the timing. In the short-term, behavioural biases have not declined, and their effects will be exaggerated by the weight of the index funds. This is why it is so important to have a longer time horizon so as to let the thesis play out to its full extent and in doing so profit from it.

What I also see is that when they were last calling the death of Buffett’s value-style of investing in 1999, in the 10 years subsequent (starting in the year 2000) Berkshire Hathaway’s book value per share rose a cumulative 87.8%, compared to the S&P500’s cumulative 12.2%.

While stocks that are called ‘value’ may have been on the nose for longer than average, the rationale for valuation-based investing is as strong as ever.

Paul Moore is Chairman and Chief Investment Officer of PM Capital. He is the Portfolio Manager of the PM Capital Global Companies Fund and the PM Capital Global Opportunities Fund (ASX:PGF). This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.