Warren Buffett was born in Omaha, Nebraska, during the depths of the Great Depression in 1930. At an early age, he showed an aptitude for maths and business, and he eventually went to the prestigious Wharton business school at the University of Pennsylvania, and later to Columbia University, where he was taught by investing legend, Ben Graham. He would go to work for Graham for a few years during the early 1950s.

USA White House, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Aged just 25, Buffett went home to Omaha from New York to set up his own investment firm. He raised US$105,000 from six investors and began managing it out of a small study in his rented home.

Over the next 12 years, Buffett pursued a Ben Graham-style of deep value investing that achieved extraordinary results: returning 31.6% per annum before fees. By the end of 1968, he was managing US$105 million on behalf of more than 300 investors. He’d grown rich in the process.

And, then, he quit. In a letter to investors, he explained why he was shutting down the fund:

- Opportunities for his style of investing had dried up.

- The market had grown overexuberant and detached from fundamentals.

- His fund had grown too large for small cap investing.

- He needed a break.

Buffett liquidated his fund and returned to investors both cash and stock in two illiquid holdings he controlled – Diversified Retail Company and Berkshire Hathaway.

The fund’s closure proved well timed. From December 1968 to May 1970, the S&P 500 fell 36%. Later, from January 1973, it would fall a further 48% over the ensuing 21 months.

Buffett wasn’t out of the game long. By the end of 1970, he built a 36% stake in Berkshire Hathway, giving him a vehicle for the ‘permanent capital’ he craved. The downturn of 1973-74 allowed Buffett to go on a spending spree and amass some of his most famous stock purchases, including Washington Post, and later, GEICO, Buffalo Evening News, and Capital Cities/ABC.

The question remains whether Buffett was a little lucky in closing his fund just before the big bear markets of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Fast forward a quarter of a century later to May 1999, and Buffett released an unusually pointed annual shareholder letter. In it, he criticized many of his fellow CEOs for manipulating earnings to keep their company share prices high.

Two months later, he gave a speech to tech and media tycoons at the famous Allen Sun Valley Conference. Alice Schroeder’s book, The Snowball, describes what happened next:

“He put up a slide to illustrate how, for several years the market’s valuation had outstripped the economy’s growth by an enormous degree. This meant, Buffett said, that the next seventeen years might not look much better than that long stretch from 1964 to 1981 when the Dow had gone exactly nowhere—that is, unless the market plummeted. “If I had to pick the most probable return over that period, he said, “it would probably be six (6%) percent. Yet a recent Paine-WebberGallup poll had shown that investors expected stocks to return thirteen to twenty-two percent.

He walked over to the screen, waggling his bushy eyebrows, he gestured at the cartoon of a naked man and woman, taken from the legendary book on the stock market, Where Are The Customers’ Yachts? “The man said to the woman, ‘There are certain things that cannot be adequately explained to a virgin either by words or pictures.’”

The audience took his point, which was that people who bought Internet stocks were about to get screwed. They sat in stony silence. Nobody laughed. Nobody chuckled or snickered or guffawed.”

Buffett’s warnings became more public in November of that year when journalist and sometimes Buffett ghost writer Carol Loomis summarized two of his speeches, including the Sun Valley one, in an article in Fortune magazine.

Buffett was widely mocked for his warnings. After all, they followed a decade of stellar returns and the advent of an Internet boom. Between 1995 and 2000, the Nasdaq Composite stock market index rose 400%. In 1999 alone, shares in Qualcomm increased by 26x and 12 other large-cap stocks each climbed over 1,000%. The Nasdaq Composite leaped 85.6% higher and the S&P 500 also rose 19.5% in 1999.

Yet, after peaking in March 2000, the Nasdaq subsequently fell 78% in one of the biggest crashes in history.

Fast forward eight-and-a-half years, and there was an even larger crisis. This time, Buffett gave few warnings about what was to come, however he did express some misgivings about the housing market in the years prior.

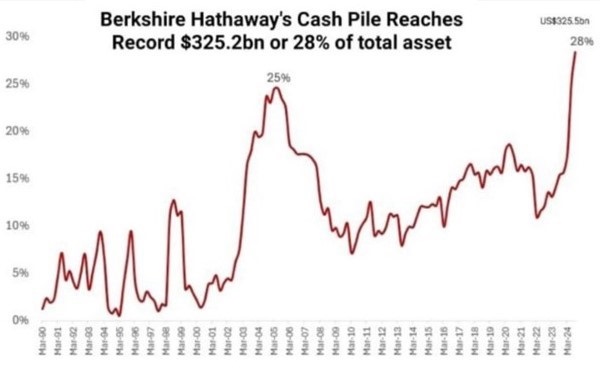

There was one tell-tale sign that Buffett was getting defensive, though: Berkshire had raised its cash levels to the highest ever in 2005 and though they came down, they remained high going into 2008.

That cash allowed him to purchase some extraordinary bargains when the financial system imploded in October 2008. When almost every other institution was struggling or on its knees, Buffett was able to provide much-needed money to a host of firms, including Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, and Dow Chemical. He ended up making a mint.

On October 16, 2008, Buffett penned an opinion article for the New York Times titled, “Buy American. I am.” It was an eloquent distillation of his famous quote: “Be fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful.”

Since that time, markets have had an extended bull market, interrupted only briefly by a worldwide virus and the 2021-2022 downturn. After bottoming at 666 in March 2009, the S&P500 is up 8.5x, or an annualised 14.4%, excluding dividends. Meanwhile, the Nasdaq is 15.8x higher, or 18.8% annualised, ex-dividends.

Buffett’s latest moves

Given this context, Berkshire Hathway’s third quarter earnings released last weekend are noteworthy. They revealed:

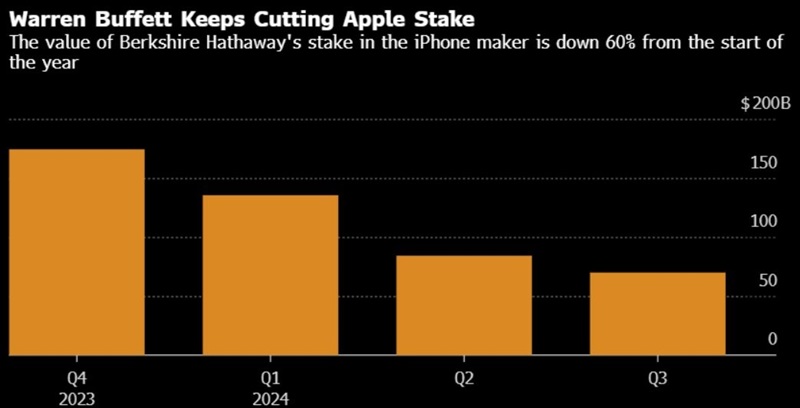

1. Buffett sold about US$100 billion in Apple (NYSE: AAPL) stock, or 25% of his stake. It means he’s sold 600 million of his 900 million shares in Apple, or two-thirds, since the start of the year.

Source: Bloomberg

2. He also sold other stocks including Bank of America (NYSE: BAC) and only made US$1.5 billion in new stock purchases.

3. The stock sales and profits from his operating businesses grew Berkshire’s cash pile to US$325 billion. That cash is larger than the company’s listed portfolio investments. Cash levels have almost doubled this year and trebled over the past two years. They are at their highest ever level as a percentage of Berkshire’s assets. Berkshire’s cash pile is now greater than the market capitalisation of 477 out of 500 companies in the S&P 500.

Source: Yahoo!

4. Buffett has continued to plough the cash into short-term Treasuries. He holds a record US$288 billion of US Treasury bills, US$93 billion more than the US Federal Reserve!

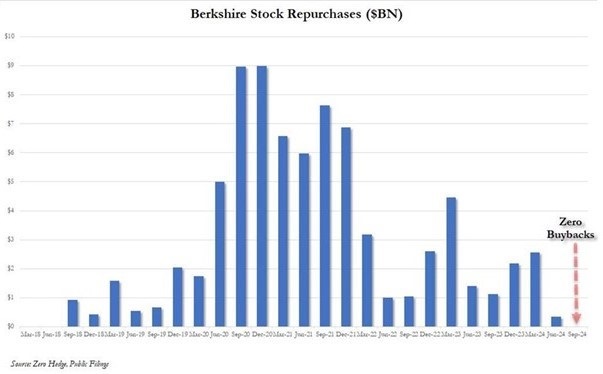

5. Berkshire didn’t buy back any of its own stock in the third quarter – the first quarter that it didn’t do buybacks since 2018.

Buffett is preparing for a bear market

One theory for Buffett’s latest moves is that the growing cash pile is to ensure Berkshire Hathaway can buy out Buffett’s stake in the company in future. While fascinating, this seems unlikely.

Much more likely is that Buffett is preparing for the next bear market. He sees that valuations for companies are getting expensive and he’s holding cash in anticipation that valuations will make more sense at some point.

Is Buffett calling for an imminent market downturn? I doubt it, but he wants to be prepared with ‘dry powder’ to take advantage of opportunities when they arise.

The situation with Apple may be more nuanced. In August, I wrote of four probable factors behind Buffett’s decision to sell down his Apple stock:

- Apple is expensive.

- It has no growth.

- He’s lost faith in management.

- He believes his money is safer in Treasuries.

I think those points are as valid now as they were then. The third point is controversial, though crucial, as I outlined in August:

“One reason for Buffett selling that I haven’t seen in any commentary is that he may have lost faith in Apple’s CEO. Buffett has said that he looks closely at leaders and how they allocate capital. Previously, he’s lambasted CEOs who’ve bought back company stock when the shares were expensive.

While Buffett has applauded Apple’s large buybacks in the past, he’s probably less happy with continued buybacks now. Why? Because buying back shares when the company was cheap made sense. With the company now expensive, it makes much less sense.”

Is it time to bunker down like Buffett?

Buffett is arguably one of the greatest-ever investors and he’s got a history of detecting both opportunities and dangers in markets. His recent earnings updates suggest that he thinks it’s now best to play defence rather than offence.

The question is whether you should follow suit. That really depends on your time horizon, risk tolerance, and circumstances.

That said, like Buffett, I’m pretty sure of four things:

- Valuations are expensive, especially in large caps in the US and Australia.

- Those valuations mean returns over the next decade are unlikely to match the last decade.

- Cash is often derided though can be an asset when it’s in short supply, especially during a market downdraft.

- Waiting for a ‘fat pitch’ requires patience and isn’t for everyone, though can be worth it.

James Gruber is editor of Firstlinks and Morningstar.