“If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” Henry Ford

“The market research is all in my head. You see, we create markets.” Akio Morita, Chairman, Sony

“People don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” Steve Jobs

Product innovations are rarely asked for or thought about by the general public. Inventors give consumers what they need without them realising that they need it. No-one ever said that they’d like a television, and Sony didn’t research potential demand for the stereo Walkman and it went on to revolutionise mobile music.

During the course of a financial year, I attend a great many fund manager presentations. In the most recent seminar I sat there thinking about how little innovation there had been in the managed funds industry in the last 15 years. Am I being harsh? Well, let’s think about it.

Most innovations happened years ago

In the early to mid-1980s when I first started investing, managed funds did not exist. Instead, a stockbroker managed your portfolio. It was inefficient and relatively expensive. Managed funds were truly an innovation. They pooled the money of many individuals and provided the benefits of economies of scale, diversification and professional management. Soon after, in the early 1990s, the ‘master fund’ was invented. Now referred to as ‘platforms’, they allowed people to invest in a number of different funds from different managers whilst providing consolidated reporting. Later, allocated pensions radically changed the ability of Australians to maximise their retirement money. These three drivers of the wealth industry were invented about 20 years ago.

Since then, just how much innovation has there been? Superficially you would think a massive amount, but how many are simply ‘line extensions’ such as long short funds, sector specific funds and some tweaking from platform providers. Colonial First State’s FirstChoice was undoubtedly innovative because it reduced the administration inefficiency and associated cost by creating pools of money instead of using third party wholesale funds. By doing so, clients are able to transact on the platform knowing they will get that day’s price and will receive a confirmation letter in a couple of days. All other platforms are simply a supermarket where you can buy other company’s wholesale funds. As such you are a hostage to that company’s administration and simple transactions can take more than a week to be actioned.

To date, the inefficiency elsewhere has perpetuated and no other institution has followed Colonial’s lead, as their platforms are tied into the old technology.

The really big innovation in recent times has been SMSFs, but for obvious reasons it wasn’t the managed fund industry that invented them. SMSFS are not just growing, they are taking off. Fuelled by a desire to take control and save money, they represent almost a third of the superannuation market and the largest segment. The fund manager response has been to promote managed funds to SMSFs, but the funds are seen as part of the problem not part of the solution.

An inflexible tax structure

And managed funds do have shortcomings. They have a trust structure, so at the end of every financial year, they are required to pay out any realised capital gains they make. If one’s objective is to invest for the long term, it’s not much help if you keep receiving taxable distributions every six months. And unfortunately, the better the performance is, the higher the distributions are. In an effort to ‘beat the index’ most active fund managers create major capital gains tax liabilities due to the incredibly high turnover (70% of the portfolio each year is not uncommon).

Some people may argue ETFs are an innovation, but they have the same legal structure and suffer the same tax fate as managed funds. Consequently, in my view they are not really much different to an index managed fund. For an individual tax payer, or an SMSF, buying shares directly means that capital gains and losses can be carefully controlled.

When you run your own SMSF, you are effectively combining your investments with those of the other members. This means you can efficiently manage the fund so that you minimise your tax. Not only did my family’s fund create sufficient franking credits to eradicate the tax on performance returns last year, it eradicated the contributions tax as well. And gave us a refund.

In 15 years of accumulating super in a managed fund that mostly invested in Australian shares, the 15% contributions tax was always deducted, never to be seen again. And I certainly never received a refund. Maybe I got some benefit in the unit price, but I doubt it. Most managed funds have such a large turnover in their portfolios that the capital gains tax on any profitable transactions eats up much of the franking credits.

Fees are too high relative to potential performance

What about the fees? Lately I have noticed an increased backlash from clients when they examine the fee structures. It is not uncommon for a global share fund to charge well over 2% per annum management fees, especially when performance fees are included. I defend many funds manager’s fees on the grounds that they have shown a historic ability to consistently beat the benchmark index. However, I recently saw a document in which one of Australia’s largest share fund managers stated a target return of 2% above the index before fees. This hardly seems a ‘stretch’ target and clients are often outraged that managers can skim off so much money for so little performance. The latest Morningstar survey on managed funds reports that the average manager in the majority of asset classes underperformed their benchmarks.

One notable recent development is ING's Living Super. The balanced option has no fees and a 50/50 cash and shares allocation, and it appeals to investors for whom perception is reality and they don't want to pay fees. The product actually pays for itself in the profit margin on the cash, which is a different approach to charging a management fee.

A growing percentage of Australians believe they can manage their own fund, outperform the professionals and save a bundle of fees. The chart below from Roy Morgan Research illustrates how poorly retail funds are perceived compared with SMSFs.

It’s debatable whether SMSFs actually do beat the professionals but the mere fact that fund managers can’t demonstrate their superiority is a worry. Surely with all that research capability and 40 hours a week at their disposal, the professionals must be able to find ‘hidden gems’ that the average part-time investor can’t?

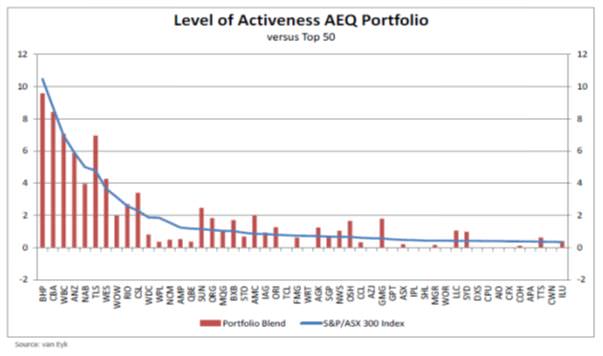

Unfortunately, the chart below shows that the professionals are mostly investing in the household names that the average SMSF portfolio already has in its portfolio (AEQ is Australian Equities in the van Eyk universe).

When asked why they don’t invest more of the fund’s money in small companies, they suggest using their small cap fund.

But I don’t want to invest client’s money in a large cap fund and a small cap fund. I want to invest client money in a diversified portfolio of shares that delivers better returns than clients can themselves. The market is littered with Asian share funds that don’t invest in Japan, and global share funds that have no exposure to emerging markets.

In truth, some of these Australian share funds are so large that it is impossible to buy enough stock in a small to medium sized company to make a difference to their performance. Can they use derivatives to gain exposure? Some can, but most have strait-jacketed themselves by an overzealous trust deed. I don’t mind if a manager judiciously uses derivatives to increase their exposure without moving the market. Or sells short stocks they think will go down. After all, Platinum has been doing it for years with pretty good results. The irony is that in the eyes of many wealth managers Platinum is somehow cheating. Platinum’s really a hedge fund, they say, whereas we’re a diversified global share manager. This sort of thinking is the hallmark of production-led companies instead of marketing-led companies. And herein lies the problem.

Most wealth management corporations entrust their new product development to non marketing people. Sure, marketers are involved, but the major thrust seems to come from the ‘factory’ which designs a product they know they can easily make, and given to the marketing and distribution departments to sell. Contrast this with consumer goods companies where marketing departments use a blend of research and gut feel to design products that can increase their company’s market share, or better still, create an entirely new category.

The wealth management industry needs to make more serious attempts to find some new cars – otherwise they will be riding their horses into the sunset.