Record levels of debt accompanied by declining asset prices means we have entered a deleveraging phase putting other spending on the backburner.

There’s a lot of chatter about the reasons why retail sales, consumer foot traffic, car sales and housing activity have plunged. From US/China trade tensions, to wobbles in the Chinese economy itself, to plunging house prices and to the upcoming federal election, analysts, brokers and commentators have taken a shotgun approach to pointing at the catalysts and causes.

The explanation however is much simpler.

Unprecedented household borrowing

In 2011, a study of the determinants of debt by the University of New England’s Sam Meng, Nam Hoang and Mahinda Siriwardana observed:

“Household debt in Australia has grown at an astonishing rate since the 1990s … the debt-income ratio jumped from 70.6% in 1990 to 162.8% in 2005. To put this into perspective, the average Australian household would have to work more than one and a half years just to pay off their debt.”

But that was then. Since 2005, Australia’s household debt has continued to soar. There is a simple explanation for the rapid increase in debt. Debt capacity is a function of its price. If interest rates halve, the borrower can ‘afford’ almost twice as much debt when borrowing interest-only, with no change in their income.

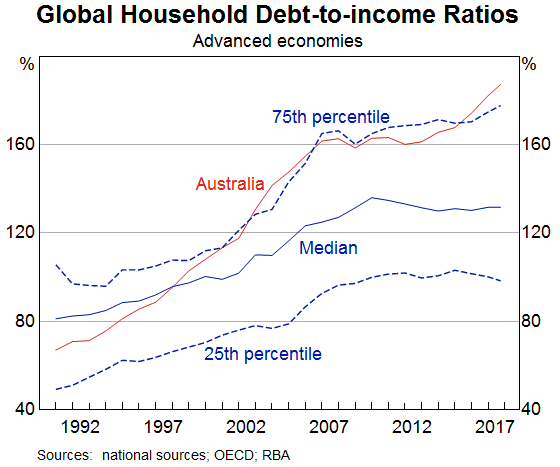

In September 2018, Michele Bullock, the Reserve Bank Assistant Governor responsible for the area that focuses on financial stability, observed that household debt in Australia has been rising relative to income for the past 30 years, and from around 70% to around 190%. Thank three decades of falling interest rates for that.

As the chart below reveals, Australia has not been unique in experiencing rising debt-to-income ratios. While the median ratio for a range of developed economies has also risen over the past 30 years, Australia’s debt-to-income ratio has risen more sharply. In fact, Australia has moved from the bottom third of countries sampled to the top quarter.

Australia’s debt binge relative to developed economies

The reason for the acceleration is householders’ belief that everyone can be a millionaire property mogul. Bullock observes, more diplomatically,

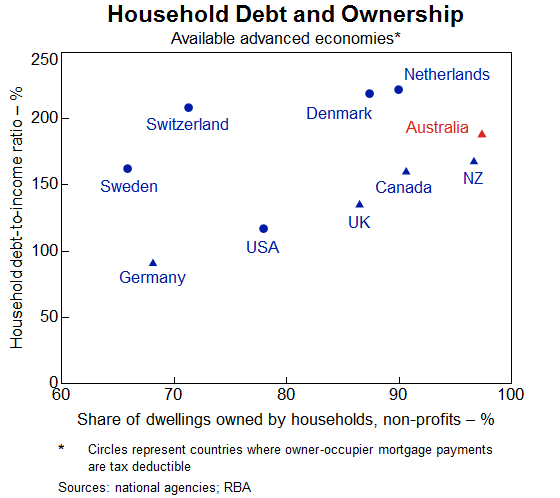

“the increase in household debt over the past few decades has been largely due to a rise in mortgage debt. And an important reason for the high level of mortgage debt in Australia is that the rental stock is mostly owned by households … This is different to many other countries where a significant proportion of the rental stock is owned by corporations or cooperatives.”

In other countries where the yield on rental properties is much more attractive, ‘mums and dads’ don’t invest as much in property. But here in Australia, where the net returns are often negative, mums and dads have piled in on top of each other to get a piece of the action In other words, would-be property moguls are committing to purchases where savvier investors fear to tread.

The proliferation of unsophisticated ‘mum and dad’ property moguls must also increase the probability of price volatility. And most busts are preceded by a period where a broad section of the population believes they can ‘get rich’.

Consequences of a period of deleveraging

On 15 February 2019, The Australian featured a story revealing terrifying house price falls. For example, for the year ending January 2019, Box Hill in NSW saw median prices fall more than 43%. In Victoria’s Red Hill, prices declined almost a third. A raft of suburbs has also fallen between 17% and 40% in just 12 months. Of course, nobody should be surprised.

Billionaire investor Warren Buffett has previously warned against any complacency surrounding debt, noting:

“It’s not debt per say that overwhelms an individual, corporation or country. Rather it is a continuous increase in debt in relation to income that causes trouble.”

In their book This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff noted that when housing booms are accompanied by sharp rises in debt, the risk of a crisis is significantly elevated.

Australia’s household debt must be reduced but the path that reduction takes has consequences for the Australian economy. One version of deleveraging allows for rising salaries to accelerate the repayment of debt but consumption still slows. A less desirable scenario sees no increase to income but rather an erosion of savings eventually forcing consumption cuts. Keep in mind, retail is the second largest employer in the country.

Finally, a much more volatile outcome adds rising mortgage interest rates (out-of-cycle possibly), which adversely impacts household budgets, producing negative equity, heavy debt burdens and a full-blown economic or financial crisis. Consumers are then left with an extremely high level of gearing, such that a small change in their income makes a big difference to their discretionary spending. The rollover from fixed rate to variable rate mortgages could be part of this income shock.

A hypothetical ability to increase debt levels allows a consumer to pay more for a property, or to spend more on goods and services beyond the amount of income earned. But when the cost of debt increases, the need to reduce debt levels sends everything into reverse. Consumers need to spend less than they earn, or the amount they can pay for a property declines. Both are now evident in Australia.

Throughout modern history, financial crises have been followed by an average of six or seven years of deleveraging. But deleveraging can occur in the absence of a crisis. This is where credit growth lags GDP growth – call it “belt tightening”. Such debt-to-GDP ratio declines, in the absence of a crisis, have been observed in Canada (1988-1994), Switzerland (1969-74), Belgium (1997-2004), Ireland (1988-1994) and in many other countries.

My biggest worry

With house prices now declining substantially, their record debt is what households will focus on. The biggest concern I have, that many analysts seem to ignore, is that after house prices begin softening, the savings ratio begins climbing, reflecting a lack of consumer confidence (note Westpac's reference to confidence 'evaporating' below) leading to a much more rapid slowdown in the economy.

Credit growth is already slowing and possibly faster than GDP. And that means a decline in retail spending, precisely what we are now seeing. Big ticket items are the first to see the tide go out. Nationally, Mercedes Benz car sales fell 43% year-on-year in November 2018 and Ford car sales fell 41%. Retail fashion sales slumped 3.8%, and as foot traffic plunged, Westpac reported consumer confidence had 'evaporated'.

Following any debt binge there must be a period of indigestion, followed by digestion. During a period of deleveraging, there is a much higher risk of negative surprises. Therefore, Australia is likely to enter a period of greater volatility in asset prices and economic conditions. For many borrowers now under water, the period of digestion will mean slow and steady repayments, for others at the pointier end of debt-to-income spectrum, expect forced asset sales.

In the meantime, whichever path is taken to reduce debt, expect retail sales and house prices to soften further. And then expect some time to pass before any sustained recovery occurs.

Welcome to the GAD – the Great Australian Deleveraging.

Roger Montgomery is Chairman and Chief Investment Officer at Montgomery Investment Management. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.