Global equity markets are facing serious and complex challenges, including expensive equity valuations, sticky inflation, high interest rates, and huge debt levels in most major economies. Whilst we think the probability is heavily in favour of a global economic slowdown, at these prices the likely long-term returns from equities are low regardless.

While high stock valuations and the cycle are the more immediate challenges, the problem of huge debt levels across developed economies is looming and could cause disruption as governments and the private sector struggle in the face of rising interest rates.

The risk is that debt to GDP levels see the numerator go up as the denominator falls. In the public and private sector, debt service ratios count as they measure the proportion of income taken up in paying interest costs. In several countries, they are at points that have historically caused problems.

The Government debt problem

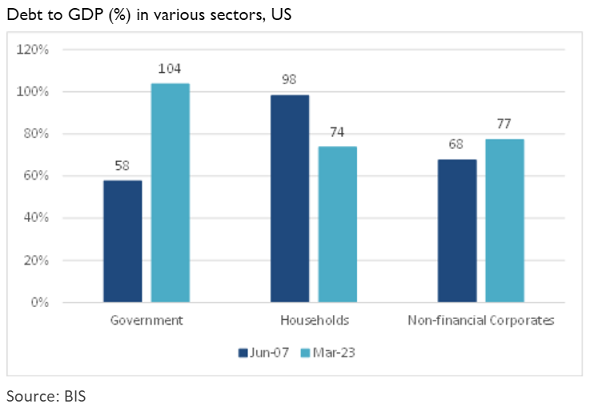

Looking at the US, the explosion in fiscal spending during the pandemic drove the country’s government-debt-to-GDP ratio to around 100%, close to the high recorded after World War II. Whilst forecasting a minuscule pullback in the short-term, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects government-debt-to-GDP to rise to 110% at the end of 2032, higher as a percentage of GDP than at any point in the nation’s history – and heading still higher in the following two decades.

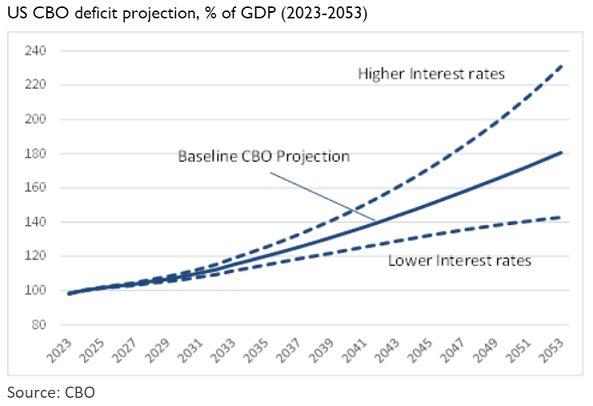

Driving this deterioration will be US budget deficits which the CBO projects should average US$1.6 trillion between 2023 and 2032 or 5.1% of GDP. In 2033, the CBO sees the US deficit at an eye-watering 6.9% of GDP, which we have only seen five times since 1946. The projections below show that the US deficit could continue to deteriorate after that.

Although like-for-like comparisons between countries are imprecise, most of the world’s major developed economies are similarly positioned. Japan, the UK and some countries in the EU are running significant deficits and many have high government public to GDP ratios. China has the same problem of huge government debt but some different economic characteristic.

Private debt a problem too

Public debt is not the only problem in the US and other developed nations; private debt is also elevated. In terms of debt service ratios (interest costs to income), countries like China (21.3%), France (20.5%) and Switzerland (20.6%) are at or close to their previous highs and above the 20% that risks triggering a crisis when interest rates are rising.

By contrast, the US (14.9%) and the UK (13.9%) are in better shape, although looking at debt levels in the US during the GFC, the position is worse in both the public and corporate sectors (as the chart below shows).

Debt levels matter now

Like so much in financial markets, debt does not matter until it does. In a world of zero or negative interest rates, debt was not a big concern. The levels of debt-to-GDP and the options available to improve the ratio have been secondary considerations for most of the previous fifteen years. But interest rates have risen quickly, significantly raising the debt burden in the US and other nations.

Investors are starting to get worried. One of the most striking recent signals has come from US treasuries, where yields have moved up sharply to reach more than 4.5%. The excess return investors require for duration risk seems to be the main driver of this jump in bond yields.

History shows that governments have only a few options to counter high debt levels, with the following usually used in combination: grow the economy, cut costs and increase taxes (austerity), default on or restructure debt, and employ financial repression, usually accompanied by inflation.

In the current environment, it seems inevitable that financial repression is coming. Financial repression is an umbrella term for measures by which a government may reduce debt via transfers from creditors (savers) to borrowers, the government itself being the most important borrower in this instance. Examples of financial repression are caps on interest rates, high reserve requirements, and transaction taxes on assets. One way or another, savers will be forced to own assets that will give them low or negative returns.

However, even with this sombre outlook, we still believe there are opportunities for investors. The good news is that interest on cash means investors have a decent starting point for capital preservation and positive returns.

We maintain the view that investors should own different equities from those that prospered from the early 2009 low to the 2022 high. Given the growth outlook, income should be given equal emphasis with capital return at a minimum. The buffer and returns from value investing should also become increasingly attractive. Equity assets with less downside and less volatility than the overall market should be more attractive than some highly valued growth assets. They will make holding on during selloffs or even leaning into weakness easier propositions whilst still providing upside. Moreover, strong balance sheets and good free cash flow generation will become important in the debt-encumbered world in which we now live.

Hugh Selby-Smith is Co-Chief Investment Officer of Talaria Capital. Talaria’s listed funds are Global Equity (TLRA) and Global Equity Currency Hedged (TLRH). This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.