Over the past 25 years, economies and markets have changed markedly, and the professional investment community has seen profound change, with competition increasing tremendously. Through this period, we have gained a number of insights that we believe will be important for us to know in the years ahead, as we continue our work trawling the world’s equity markets for outstanding equity investments.

These insights are:

Daring to be different – with conviction

All investors have to decide what type of investor they are. Passive investors and benchmark huggers have implicitly accepted index returns at best while having little risk of losing significantly, at least in a relative sense. Active investors disregard the false sense of security of a benchmark and aspire to returns that are better than average or even great. Going for greatness has its price, however: it is typically quite uncomfortable, because by definition disregarding the benchmark means taking radically different decisions than the market, and it is always uncomfortable not being part of the crowd. Deviating from the crowd is a prerequisite for great results but no guarantee, as you could also be wrong. Are you willing to be different and are you willing to be wrong? If so, it means that you as an investor have a choice: you can go for safety and seek index returns, or you can aspire to great results but with significantly higher risk.

All of our high-conviction positions throughout the life of our business as an asset manager have at times felt uncomfortable and looked wrong from a conventional point of view. Our major exposures in oil stocks in 2002-05 comes to mind. Like our zero weighting in oil and other energy companies since 2012. Today it seems obvious to be out of oil stocks at that time, but this was not conventional wisdom back then.

Being an active and concentrated stock picker also requires the organisation to think long-term and your clients also to be focused on the longer-term returns. Even though you as an investor will eventually prove right in your thinking, the timing may go against you. Performance is not linear: actually, our experience is that it is very lumpy. As Keynes observed, “The market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.”

Earnings growth is the long-term driver of share prices

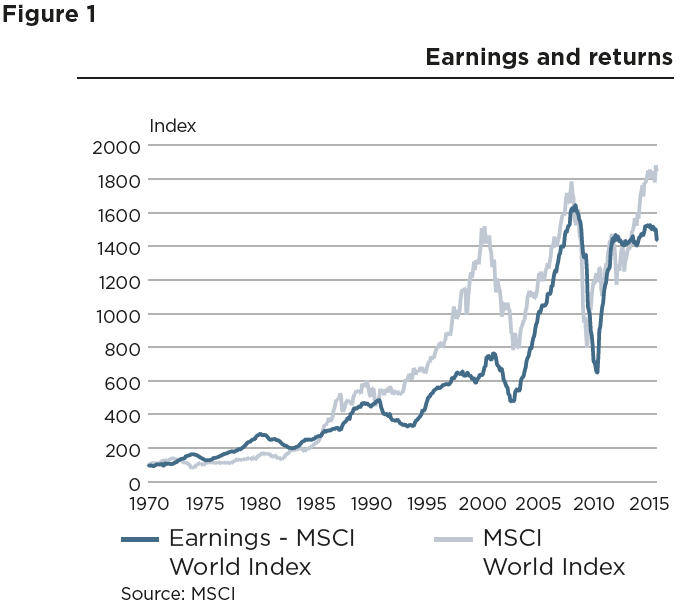

We firmly believe that the long-term trend in earnings determines the returns that investors receive from investing in equities. This belief is supported by historical facts, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Since 1970, earnings have risen by 1,337% (USD), supporting equity returns of 1,747% (USD). Throughout this period, there have been time spans when equity markets have deviated from trend earnings growth creating shorter-term opportunities or risks. However, timing these events is difficult. Furthermore, we believe that the compounding of returns is a much less risky way of generating superior long-term returns than trading in and out of stocks and segments of the market in a desire to outperform the market.

To quote ice hockey champion, Wayne Gretzky, you “skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been”, and you never invest in the present. It does not matter what a company has earned. You have to predict with a fair degree of certainty what the company will be earning in the future.

One example could be Nestlé, a company we have invested in since our inception back in 1990. Over these past 25 years, Nestlé has delivered growth in earnings per share of approximately 10% per annum, and at times the share price has looked somewhat expensive. Our view has been that structural themes such as ‘premiumisation’ and growth in emerging markets continue to support the company and that the growth outlook has not changed, supporting the view that the company would ‘grow into its multiple’. Over this period, Nestlé has delivered a total return of 2,200% (USD), or 13.5% per annum, versus the global equity market return over the same period of 420% (USD), or roughly 6.8% per annum. Nestlé today trades at 20 times 2016 earnings, which is expensive, versus its own history (because of low interest rates) but in two years’ time the company will be trading at about 16-17 times 2018 earnings with an unchanged share price. As we do not see any change to Nestlé’s growth outlook for the coming years, we think it is unrealistic to expect a de-rating of the valuation multiple for the company and thus believe that the stock will continue to deliver its low double-digit return.

Business model is more important than stock valuation

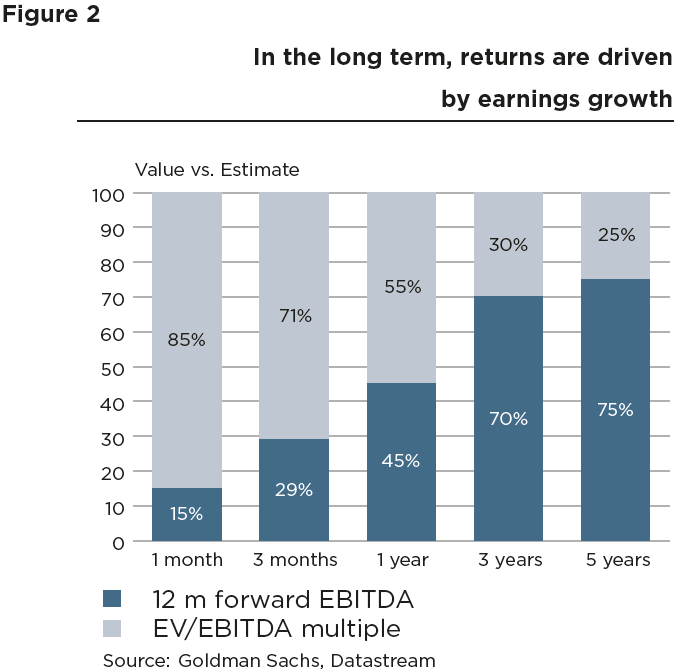

Considering valuation is useful, especially if you have a shorter time horizon. However, for longer-term investment horizons, it is less useful. This is because over longer-term periods the earnings power of a superior business comes to the fore and directly drives the bulk of the performance. Timing and therefore valuation becomes less important, and the quality of the business becomes increasingly important for the long-term return, as can be seen in Figure 2.

For this reason, our main focus is to identify high-quality growth companies that will continue to deliver high returns on invested capital, thereby reducing the likelihood of multiple contraction. As Warren Buffett famously said, “Price is what you pay. Value is what you get.” We do not want to pay exorbitant multiples for a stock, but we would rather pay a bit too much for the really excellent business than too little for the poor business.

Mistakes made and lessons learnt: think about political risk

Being an active investment manager means taking active and at times controversial bets, which of course is not risk-free, as mistakes will be made. The importance in being wrong is, obviously, not to be wrong too often and, when you are wrong, trying to understand what made the investment a losing proposition.

Around the turn of the century, we were invested in two Nordic stocks, Tomra and Vestas, both of which were horrible investments and had a common problem. Tomra was the largest producer of reverse vending machines used for the recycling of beverage containers. Our conviction was that the company was exposed to strong secular growth as the recycling standards spread from the Nordic region, where the system had been very successful, to other parts of Europe and eventually to the Americas.

In Vestas, the investment case was built on an idea of strong secular growth as wind turbines spread across the globe supported by countries’ desire to increase self-sufficiency in power generation and reduce carbon emissions.

We sold both stocks after realising large losses on the investments. However, not everything was lost: we learned a very important lesson, namely that you should be very careful with companies that depend on political decisions to realise their growth potential. Tomra began to go wrong when the required legislation in Germany was not implemented and the large supermarket chains did not feel obliged to invest in new collection systems. Vestas’ growth spurt ended when expected orders from the US evaporated because the US subsidy schemes were not implemented as anticipated.

Too much time is spent on temporary information at the expense of lasting knowledge

We live in times of great uncertainty. We question how much performance one could generate from trading the news on Greece. Too much time is spent on this kind of temporary news rather than focusing on creating lasting knowledge you can use to position your investments for long-term performance. Too much time is spent on thinking about whether it’s ‘risk on’ or ‘risk off’ instead of focusing on factors about which you as an investor stand a decent chance of being correct – over the long term. A case in point could be our decade-long focus on the developing middle-income consumer base in India. When we initially invested in the Indian mortgage bank HDFC in 2005, India had an estimated middle-income population of about 50 million. Today that has increased to more than 250 million and is expected to be around 500-600 million by 2025, larger than the entire population of the European Union. When did you read in the newspaper that the middle-income population of India had just doubled?

Since our initial purchase of HDFC in 2005, the stock has risen 460% (USD) versus a rise of the global equity market of only 90% (USD). We think it is much more important to recognise this unstoppable force than to spend your time evaluating the numerous possible outcomes of the Greek tragedy and the impact it could have on asset markets – something that is highly uncertain to forecast.

Even in times of low economic growth, find pockets of high growth in thematic investments

Investors usually expend significant resources trying to predict the general macroeconomic trend, since nominal economic growth over the long term determines the earnings growth of companies. However, history has also proved that there is no direct relationship between short-term economic cycles and stock market returns.

Even during periods of low economic growth, you can always find pockets of high growth in the world economy. Over the past three years, we have seen unusually low economic growth in the Western world of approximately 2% on average and, despite this, we have identified pockets of growth. One example could be Novo Nordisk and the obesity epidemic.

Other current focus areas for us are the expansion in middle-income groups in India and other emerging economies and robotics, where we continue to see strong growth from the large-scale industrial application of robots as well as from the new emerging theme of collaborative robots. Sensors are at the core of optimisation of industrial processes as well as for improved car safety and eventually fully autonomous cars and the build-out of the Internet of Things, where machines, appliances and humans are connected in one giant network. If you can afford to step away from conventional wisdom and the benchmark, you can always find pockets of secular growth.

Conclusion

Since 1990, when we initiated our global equity strategy, the world has changed in unpredictable ways. Themes have come and gone, companies have flourished and faltered, and countries have emerged and developed whilst others have lagged. The asset management industry has changed significantly, and the abundance of information and data has shortened investment horizons.

There are important insights from the 25 years of actively managing global equities, involving consistently identifying themes and trends that drive earnings growth and hence share prices. The lasting knowledge will guide us in the years ahead.

Morten Springborg is a Global Thematic Specialist at Carnegie Asset Management, a BNP Paribas Investment Partner. This article is for general educational purposes and does not consider the specific circumstances of any person. Investors should take professional advice before acting.