Hands up any home-owning retiree who would prefer to have $500,000 in other assets rather than $1 million. Anybody? What, nobody? I thought so.

So why did the headline in The Australian Financial Review of 7 April 2018 state, “When $1m is worth less than $500,000”, and leading names in superannuation offered their support for the claim? The respected SMSF specialist, Meg Heffron, tweeted,

“This is such a good article … And one of the worst things about this is not that it’s dumb policy, it’s the demonisation of people like the Smiths who have saved and sacrificed to get their $1m.”

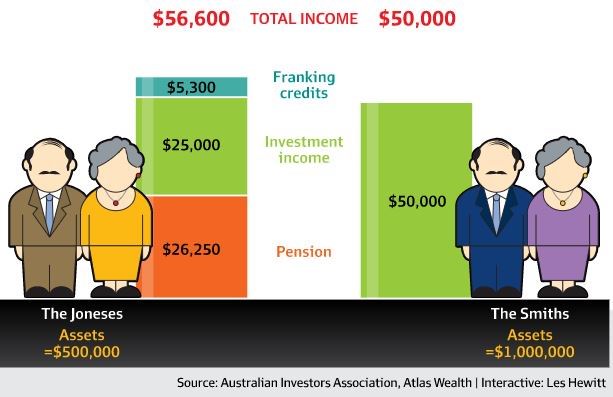

Meg is right about demonising the wealthy, but the heading is wrong. The AFR article was accompanied by the following graphic:

The analysis assumes both the Smiths and the Joneses invest half their money in a balanced portfolio earning 5% and the other half in fully-franked shares. Due to the proposed Labor policy of allowing franking credit refunds for pensioners (worth $5,300 to the Joneses) plus the age pension itself (worth $26,250 to the Joneses), apparently the Smiths with $1 million are “worth less” than the Joneses with $500,000.

Accessing money to live on

Two simple examples show how the “worth less” claim can never be true.

First, suppose the Smiths renovate their house for $500,000 and otherwise retain the rest of their net worth by holding $500,000 in assets other than their home. Now they are in the same position as the Joneses regarding income. They receive franking credits and the age pension, plus they have a beautiful extension to enjoy in their later years. In future, the Smiths will have more money if they sell their more valuable house and downsize (and perhaps put it into superannuation from 1 July 2018 using the new downsizer contribution rules). They may even access more money if necessary through a higher reverse mortgage, for example.

Clearly, the Smiths are better off than if they started with only $500,000.

Second, in case anyone argues the AFR article is more about ‘money to live on’, a previous article in Cuffelinks by Gordon Thompson charts how a wealthier pensioner is better off by drawing on capital to supplement income. This is a legitimate retirement superannuation strategy. In fact, governments have often stated the intention of superannuation is not a tax-advantaged bequest scheme but to finance a retirement including drawing down capital. As Thompson says, “The goal of a retirement income strategy should be to maximise the retiree’s sources of cashflow over time. This can be achieved by drawing down savings in combination with a part pension.”

Here’s the crucial point some people are missing.

Once the Smiths have enjoyed living off the extra money, they still have $500,000, which is as much money as the Joneses. In fact, the Smiths will receive a part-pension as soon as their non-home assets fall below $837,000 when they also become eligible for franking refunds (assuming they do not invest via a SMSF, where the cut-off date for the ‘pension guarantee’ is proposed as 28 March 2018). The more they draw down on their capital, the more the age pension rises.

Real life for the Joneses and Smith

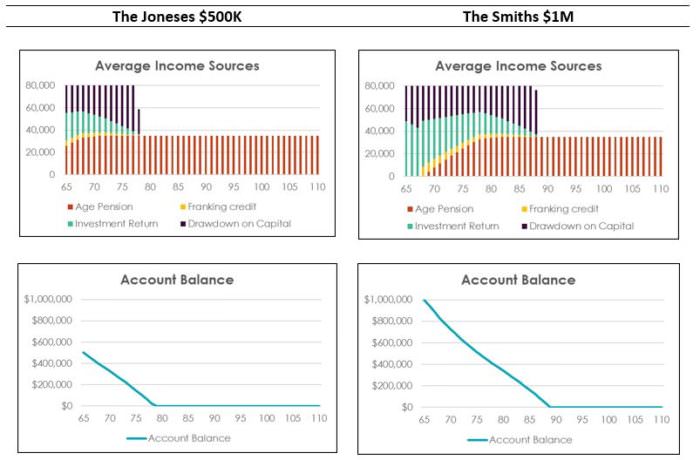

Let's re-examine the numbers with the same assumptions as above (all are homeowners aged 65, the two couples have a zero marginal tax rates and receive franking credit refunds when they are eligible for the age pension (full or part), current age pension rules apply and calculations are presented in real term with the inflation rate at 2.5%).

Let's assume both couples want a better lifestyle and live on $80,000 initially from the age of 65. The charts below divide the $80,000 of 'income' or 'cash flow' into four components:

- Age pension

- Franking credit refunds

- Investment returns

- Capital drawdowns

The charts show how the age pension and franking credit refunds kick in for the Smiths and how rapidly investment income falls for the Jones as they drawdown their capital.

The Smiths will reach the age of 88, or 23 years in an $80,000 lifestyle, before they exhaust their capital and rely on the age pension. If the Joneses wanted this lifestyle, their capital would be exhausted at age 78, a decade earlier than the Joneses. It would take the Smiths until the age of 75 or 10 years to reach the $500,000 held by the Joneses when they were 65. So much for the Joneses being better off.

Smiths versus Joneses based on $80,000 annual expenditure

The AFR article only considers the first year. As the Smiths spend more, they start to receive their franking credits and their age pension grows rapidly. Note that as these calculations are done in real terms, the 5% return on investments is only 2.5% and this also reduces the account balance.

We have run many simulations at different income levels and there are no circumstances where it’s better to have $500,000 than $1 million.

Overstating the disincentive to save and the black hole

A similar argument is often made against the Turnbull Government’s changes to the age pension taper test and thresholds which took effect on 1 January 2017. Some articles say it’s better to spend excesses above thresholds on ‘whatever you please’, almost as if it’s good to get rid of the money to qualify for more age pension. An extra $23,000 in age pension is 7.8% risk-free on $300,000, achieved by reducing assets from $800,000 to $500,000.

For example, the SMSF Association CEO, John Maroney, wrote on 9 January 2018:

“For home-owning couples who have a superannuation balance between $500,000 and $800,000, the increased taper rate creates a ‘black hole’ where their assets above the asset test free amount cause them to be worse off in terms of income. This is caused by the taper rate of the equivalent of 7.8%, reducing their pension entitlement at a rate exceeding the income they earn from their superannuation balance above the asset free area.”

John is right in specifying ‘in terms of income’, but superannuation involves a calculated drawdown of capital for most people. This is not only about 'income' but access to money and cash flow. The person with $800,000 or $1 million is better off because they have substantially more capital to draw on. They will go onto the age pension after they have enjoyed spending part of their extra capital.

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Cuffelinks. My thanks to quantitative analyst Estelle Liu for assisting with the calculations.