There’s no shortage of issues facing people planning for their retirement. One that needs tackling is the threat worsening housing affordability and falling home ownership will present to the retirement incomes of many Australians.

How ownership critical for comfortable retirement

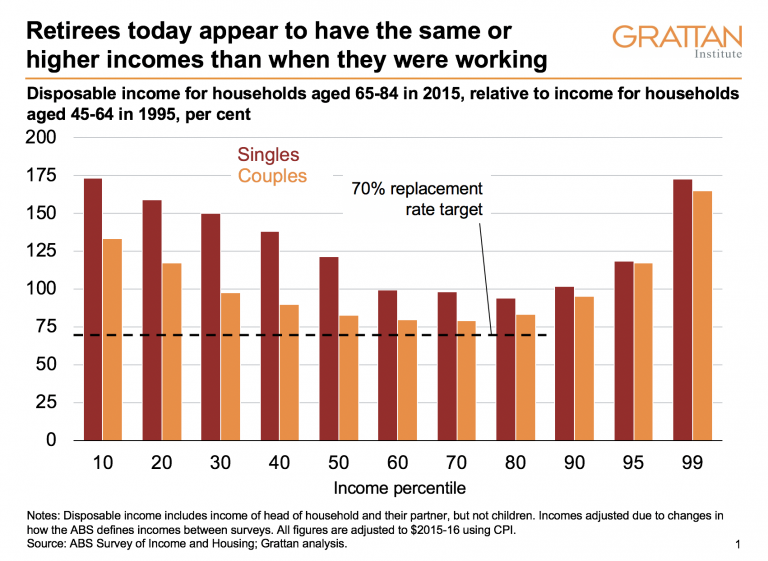

Most retirees today feel more comfortable financially than younger Australians who are still working. Retirees are less likely than working-age Australians to suffer financial stress such as not being able to pay a bill on time and are more likely to be able to afford optional extras such as annual holidays.

In fact, most people aged 65-84 today have as much or more income than they did 20 years ago when working. And while the age pension is by no means generous, it does keep most low-income retirees out of poverty – provided that they own their home.

As for future retirees, Grattan Institute research shows that most working Australians today can look forward to a standard of living in retirement that’s on par with their standard of living while working, and often higher. Retirement incomes also remain adequate for most Australians even when they work part-time or take significant career breaks, such as to care for children.

But we’re failing retirees who rent

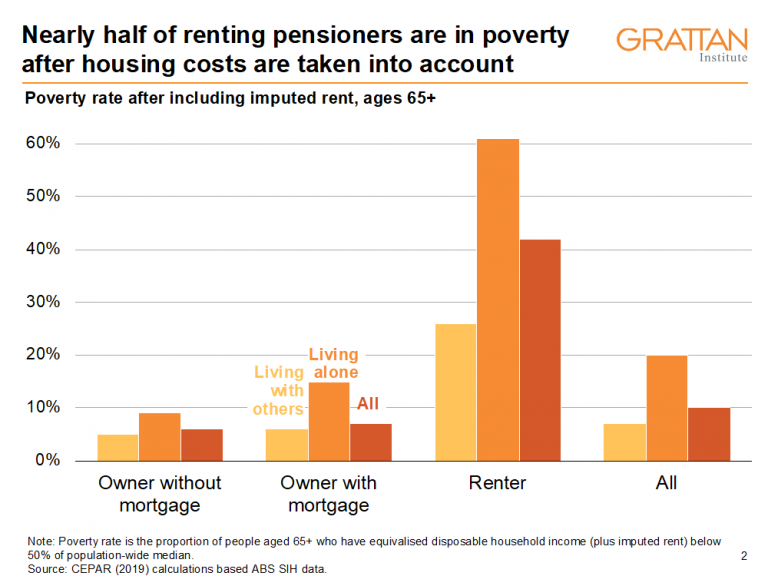

Not all Australians enjoy a comfortable retirement. Senior Australians who rent in the private market are much more likely to suffer financial stress than homeowners or renters in public housing. Nearly half of retired renters are in poverty once housing costs are taken into account.

The explanation is simple: retirees spend a lot less on housing as they pay down their mortgage, but housing costs keep rising for retired renters. The typical homeowner aged over 65 spends just 5% of their income on housing, compared to nearly 30% for renters.

More retirees will rent in future

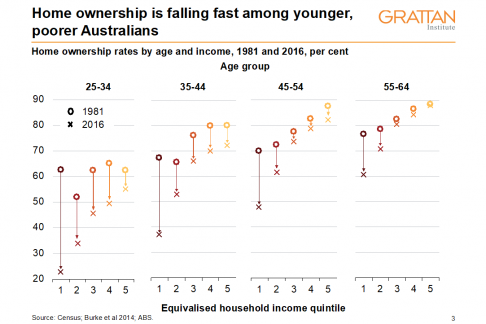

The proportion of retired renters in financial stress will increase because younger people on lower incomes are less likely to own their own home than in the past.

Between 1981 and 2016, home ownership rates among 25-34-year-olds fell from more than 60% to 45%. Home ownership has also fallen for middle-aged Australians. Home ownership now depends on income much more than in the past: for 25-34-year-olds, home ownership among the poorest 20% has fallen from 63% to 22%.

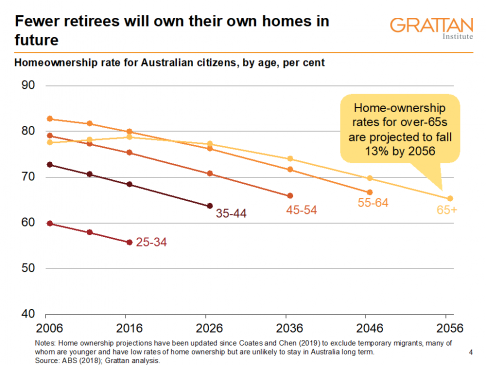

Today’s younger Australians will become tomorrow’s retirees. These trends suggest that by 2056 just two-thirds of retirees will own their homes, down from nearly 80% today.

So what should the federal government do?

Boosting Rent Assistance should be the priority

The government’s first priority should be boosting Commonwealth Rent Assistance, which has not kept pace with rent increases over the past two decades. Raising Rent Assistance by 40%, or roughly $1,400 a year for singles, would cost just $300 million a year if it applied to pensioners, and another $1 billion a year if extended to younger renters as well.

And in future, Rent Assistance should be indexed to changes in rents typically paid by people receiving income support, so that its value is maintained. Boosting Rent Assistance would do much more to reduce poverty in retirement per government dollar spent than the alternatives, including lifting the age pension.

A common concern is that boosting Rent Assistance would lead to higher rents. But that’s unlikely: households would not be required to spend any of the extra income on rent, and most would not.

More social housing is needed but not for everyone

There is also a powerful case for more government funding of social housing, including for vulnerable older renters at risk of homelessness. It would also be an effective economic stimulus given COVID-19. But boosting social housing will be expensive. Increasing the stock by 100,000 dwellings would require additional ongoing public funding of about $900 million a year, or upfront capital expenditure of $10-$15 billion.

It would be prohibitively expensive to provide enough social housing to accommodate all renting pensioners, let alone all working-age Australians on low incomes. So any boost to social housing should be reserved for people at greatest risk of long-term homelessness.

Include the home in the pension assets test

The age pension exacerbates the divide between the housing ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ in retirement by favouring homeowners over renters. Once a person is retired, their home is treated differently to their other assets. Under current rules only the first $210,500 of home equity is counted in the age pension assets test. Which is why $6 billion in pension payments go to people with homes worth more than $1 million.

It’s time for more of the value of the family home to be included in the pension assets test, above some threshold such as $500,000 would be fairer and would save the budget up to $2 billion a year.

No pensioner would be forced to leave their home. Instead this change would primarily reduce inheritances. Pensioners with valuable homes could continue to live at home and receive the pension under the government’s Pension Loans Scheme, which recovers debts only when homes are eventually sold.

A $500,000 threshold would ensure that homeowners would still have substantial equity to pass on to their beneficiaries. It would ask people with high levels of wealth that would otherwise be passed on to heirs to use some of this wealth to support themselves in retirement.

Higher house prices also mean that Australians are spending more of their lifetime incomes buying a house and paying it off by the time they retire. Yet few retirees draw down the value of their home to fund their retirement, either by downsizing or by borrowing against home equity.

Unless Australians are willing to draw on their home equity in retirement, rising house prices mean Australians will be left with lower living standards both while working and in retirement.

Brendan Coates is the Household Finances Program Director and a Fellow at Grattan Institute. This article is general information and not personal advice.