On Monday this week, Westpac ruled off the 2018 financial year profit results for the Australian banks. In the words of Queen Elizabeth, 2018 could only be described as an annus horribilis for Australian banks and their investors. The CEO of one major bank lost his job, the revelations of the Financial Services Royal Commission resulted in remediation provisions and a spike in legal fees (which should see new sports cars and houses at Palm Beach for sections of the legal community this Christmas), fines were levied and credit growth slowed. An environment of fear has weighed on bank share prices.

There are common themes emerging from the banks in the 2018 reporting season. We will differentiate between the major trading banks and hand out our reporting season awards to the financial intermediaries that grease the wheels of Australian capitalism.

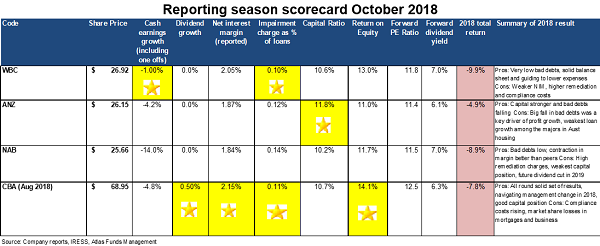

Click to enlarge

Scaling back the empire

The main theme from 2018 was the breaking down of the allfinanz model that the banks built up carefully over the past 30 years. Allfinanz or bancassurance refers to the business model where one financial organisation combines banking, insurance and financial services such as financial planning to provide a financial supermarket for their customers. This is based on the somewhat false assumption that the bank's employees can efficiently cross-sell different financial products to their existing customers at a lower cost than if this was done by separate financial institutions. It creates some of the conflicts of interest that have been on display at the Royal Commission.

Over the past year, the Commonwealth Bank sold its life insurance business to AIA and the asset management business a week ago to Mitsubishi UFJ for a very solid price. Similarly, ANZ exited both its wealth management and life insurance businesses. NAB also announced plans to sell MLC by 2019. Additionally, Westpac has reduced its stake in BT Investment Management (now renamed as the Pendal Group). These moves acknowledge that creating vertically-integrated financial supermarkets was a mistake. If adverse rulings are made on vertical integration in the Royal Commission’s Final Report, most of the banks will have already made moves to simplify their businesses, so shareholders won’t be exposed to significant 'fire sales' of assets by motivated sellers.

Profit growth hit by remediation

Across the sector, profit growth was subdued in 2018 as the banks grappled with slowing credit growth, the application of tighter lending standards, customer remediation and legal costs. The table above looks at the growth in cash earnings inclusive of these costs. Whilst many companies encourage investors to look through these charges, ultimately these are real costs that impact the profits available to shareholders, and in aggregate the four banks have set aside $1.3 billion to cover customer remediation.

Westpac reported the strongest cash earnings by cost control, very low bad debts and a lower level of customer remediation charges. NAB brought up the rear due to both $755 million in restructuring costs and $435 million in customer remediation charges.

Bad debts stay low

A big feature of the 2018 results for the banks has been the ongoing decline in bad debts. Falling bad debts boost bank profitability, as loans are priced assuming that a certain percentage of borrowers will be unable to repay. Additionally, declining bad debt charges year on year creates the impression of profit growth even in a situation where a bank writes the same amount of loans at the same margin. Bad debts fell further in 2018, as some previously stressed or non-performing loans were paid off or returned to making interest payments. The main factors causing this fall has been the low unemployment rate and a near absence of major corporate collapses over the past 12 months.

Westpac and Commonwealth Bank both get the gold stars with very small impairment charges courtesy of their higher weight to housing loans in their loan book. Historically home loans have attracted the lowest level of defaults.

Shareholder returns hold as dividends steady

Across the sector, dividend growth has essentially stopped, with Commonwealth Bank providing the only increase, two cents, over 2017. In an environment where loan growth is slowing, provisions rising and the management teams regularly appearing either in front of the Royal Commission or before our political masters in Canberra, it would be imprudent for the banks to raise dividends.

In 2018, dividends were maintained across the banks, which was a surprise in the case of NAB. It paid $1.98 in dividends on diluted cash earnings per share of only $2.02, a very high payout ratio and not a sustainable situation given that the bank’s capital ratio is below the APRA target of 10.5%.

Looking ahead, dividend growth is likely to be subdued in 2019, as the banks digest the outcome from the Royal Commission. ANZ and Commonwealth Bank shareholders can expect capital returns in the form of share buy-backs to offset the dilution from asset sales. In 2018, ANZ bought back $1.9 billion of its own stock, with an additional $1.1 billion due over the next six months. The major Australian banks in aggregate are currently sitting on a grossed-up yield (including franking credits) of 9.4%, an attractive alternative to term deposits.

Interest margins

The banks’ net interest margins [(Interest Received - Interest Paid) divided by Average Invested Assets] in aggregate declined in 2018, reflecting higher wholesale funding costs and borrowers switching from interest only (which attracts a higher rate) to principal and interest mortgages. This switching was done in response to regulator concerns about an overheated residential property market, and in particular the growth in interest-only loans to property investors. Looking ahead to 2019, margins should recover courtesy of a rate rise of around 0.15% announced in mid-September. All the banks put through a similar rate rise with the exception of NAB, and it will be interesting to see whether NAB increases its market share as a result of this or follows suit at a later date.

Total returns including share prices

All the banks have delivered negative absolute returns, also trailing the S&P/ASX200 which eked out a small gain of 0.24%. The uncertainty around the outcomes from the Royal Commission, rising compliance costs and slowing credit growth has weighed on their share prices. Westpac has been the worst-performing bank, mainly due to concerns about lending standards in the $400 billion mortgage book, though we are yet to see any adverse evidence in the form of rising bad debts.

– No star given –

Our overall view of the future

It is hard to be a bank investor at the moment and some fund managers are advocating avoiding them all together.

We view that at current prices, investors are being paid an attractive dividend yield to own solid businesses that have a long history of finding ways to grow earnings and navigate political minefields. Looking at the wider Australian market, the banks look relatively cheap, are well capitalised and unlike other income stocks such as Telstra, should have little difficulty maintaining their high fully-franked dividends. Additionally, the share prices of ANZ and Commonwealth Bank will see the benefit of share buy-backs, as the proceeds from the sales of non-core assets are received. The key bank overweight positions in the Maxim Atlas Core Equity Portfolio are Westpac, ANZ and Macquarie Bank.

Hugh Dive is Chief Investment Officer of Atlas Funds Management. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.