For much of the last decade, the profit results for the banks were rather simple to analyse. Coming out of the GFC, the major trading banks steadily grew profitability on the back of solid credit growth, declining bad debt charges and reduced competition as foreign competitors either exited the Australian market or were taken over.

However, over the past two years, the profit results of the banks have become increasingly complicated to analyse. The Financial Services Royal Commission resulted in extensive remediation provisions, increased compliance costs and a spike in legal fees, at a time where credit growth has slowed dramatically and interest rates have moved towards zero.

Additionally, Commonwealth, ANZ and Westpac all divested divisions, primarily in wealth and insurance, the areas of their businesses that were the source of the majority of their remediation charges.

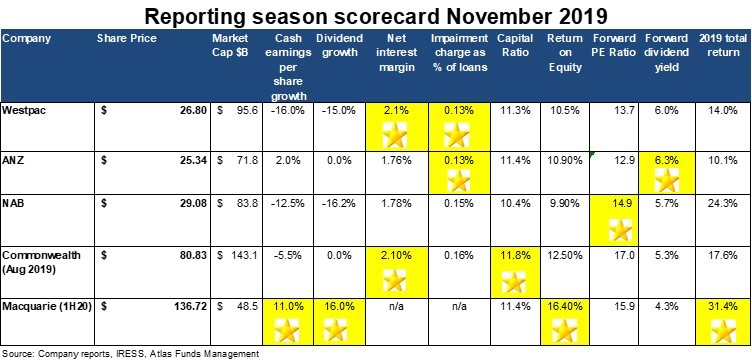

This update looks at the themes in the approximately 800 pages of financial results released over the past 10 days by the financial institutions that grease the wheels of the Australian capitalism. We will award gold stars based on performance over the past year.

Remediation

Customer remediation was a key theme for the results in 2019, with banks compensating customers or taking provisions related to financial advice, banking, insurance and consumer credit.

Australia’s banks have taken remediation provisions over the past 12 months of between $826 million (ANZ) and $1.1 billion (Westpac and CBA), with NAB around the $1.4 billion mark. ANZ’s lower level of provisioning does not reflect any lack of prudence, but rather their historically lower level of exposure to financial advice and funds management. NAB’s higher level reflects their desire to put MLC on solid footing before either selling or listing it in 2020.

No star is given. The fact that the banks have made these provisions is bad for both their customers and shareholders.

Capital

While all banks have core Tier 1 capital ratios above the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) ‘unquestionably strong’ benchmark of 10.5%, boosting capital was a feature of bank results in 2019.

Westpac increased its capital via both a $2.5 billion equity raising and cutting the dividend, ANZ and CBA saw capital increase after selling wealth and insurance divisions and not buying back shares to neutralise the earnings per share impact and NAB’s final dividend was partially underwritten.

Normally, increases in capital are only required when a bank is either substantially increasing its loan book or writing off the value of assets in a recession, neither of which is facing the banks in 2019. It is an environment of anaemic credit growth and low bad debts. These moves are in response to potential changes to capital requirements across the Tasman discussed below and APRA’s moves to retain capital in the Australian banking system.

New Zealand

New Zealand’s banking market is unusual in the developed world in that around 90% of lending is done by foreign banks. The subsidiaries of Australia’s major four banks and the country are a major capital importers. While this market dominance is often portrayed as a takeover of the New Zealand banking system by sinister Australian institutions, the concentration of market power is primarily due to the collapse of New Zealand owned banks in the 1980s, with these banks being taken over and recapitalised by Australian banks.

Late in 2018, the RBNZ released a consultation paper on bank capital requirements, essentially saying that they would like the banks operating in New Zealand to lift their Tier 1 Capital from 8.5% to 16%, well above APRA’s Australian standard of 10.5%. The impact of this decision (if implemented) would be for the Australian banks to inject around to A$12 billion into their NZ-based subsidiaries.

The RBNZ consultation paper is based on the naïve assumption that Australian shareholders would blithely fund New Zealand’s aspirations to be the best-capitalised banking system in the world, without any impact on pricing of mortgages in New Zealand or overall credit availability in the shaky isles. In December 2019, the banks will gain clarity as to how the RBNZ intends to implement its plans and in response, all of the banks other than NAB are carrying high levels of capital.

In its results, NAB took the most aggressive tone, suggesting that they will reduce lending in New Zealand and reprice loans, an interesting move given that in 2019 New Zealand was NAB’s most profitable market and the only division in NAB that saw higher cash profits. If New Zealand’s capital requirements turn to be less onerous than expected, investors may expect share buybacks from ANZ and CBA.

Profit growth

Bank profit growth reflected anaemic credit growth, falling interest rates and significant remediation charges, with earnings per share across the major banks declining by -8%. While some analysts and the banks themselves ignore these charges and talk about 'normalised earnings', we see this as specious logic. These remediation charges are not non-cash accounting charges, but actual cash outflows that impact shareholder dividends.

ANZ Bank grew cash profits per share by 2% courtesy of a strong performance by its institutional bank and taking most of their remediation medicine in 2018. However, the gold star goes to Australia’s global investment bank, Macquarie, which stands out with an 11% growth in earnings per share. Macquarie’s rising earnings per share is due to both successful expansions offshore and sidestepping most of the issues revealed by the Royal Commission.

Dividends

In 2019, NAB and Westpac cut their dividends to more sustainable levels, while ANZ and CBA kept its dividends steady. Macquarie sharply increased its dividend ahead of profit growth, a luxury afforded to Macquarie by its low dividend payout ratio. Across the major banks, ANZ has the highest dividend yield at 6.3%, though this may be at risk in 2020 if the bank does not buy back stock to neutralise the impact of lost earnings from the sale of its insurance and wealth management divisions.

Bad debts

One of the biggest drivers of earnings growth over the last few years has been the ongoing decline in bad debts. Falling bad debts boost bank profitability, as loans are priced assuming that a certain percentage of borrowers will be unable to repay, and that the bank will incur a loss on the loan. Over the past few years, when analysts look through a bank’s financial statements one of the first numbers checked is the bad debt charge. Even a small rise may be interpreted as the start of a trend back to a normalised long-term level of bad debts around 0.3% of total loans.

Bad debts remained low in 2019, with Westpac and ANZ reporting the lowest level of bad debts of a mere 0.13% of the loan book, aided by a stabilisation in the East Coast property market and improving affordability stemming from several interest rate cuts. On the business side there were no major corporate collapses over 2019.

Very low interest rates

Over the past 12 months the RBA has cut the cash rate from 1.5% to a historic low of 0.75% and the standard variable rate for an owner-occupier mortgage has fallen from 4.7% to 4.1%.

While lower rates are positive for borrowers, low rates impact bank profitability and in particular their net interest margin. In 2019 the banks’ net interest margins [(Interest Received - Interest Paid) divided by Average Invested Assets] decreased across all banks. The fall was attributed to increased competition, customer remediation charges and the reduced funding benefit from the bank’s pools of deposits.

For example, NAB has $88 billion in deposits that are currently earning interest rates close to zero, as lending rates fall and the bank (unlike the Swiss banks) cannot charge negative interest rates. The profit margin gets squeezed.

In his presentation to the market, NAB’s CEO made an interesting point that the RBA’s rate cuts were not achieving their goal of stimulating the Australian economy. He saw that borrowers were not reducing their monthly payments to spend on consumer goods and savers such as retirees who are likely to spend all of their interest income are getting a much lower rate on their term deposits. Thus, very low interest rates result in a wealth transfer between savers who would otherwise be spending their interest income to reducing the debts outstanding for borrowers, with a minimal positive impact on the economy.

Westpac and Commonwealth reported the highest net interest rate margin in 2019 which reflects both their greater focus on mortgages (which attract a higher margin than business loans) and the lower loan losses on mortgages compared with business loans.

Our take

We expect the banks to deliver around 3-5% earnings growth as they face low credit growth and increased regulatory scrutiny. There remain significant cost saving opportunities from rationalising their 1,000 branch networks around Australia as the nature of banking changes to digital interactions.

However, if investors examine the wider Australian market, the banks look relatively cheap, are well capitalised, and should have little difficulty in maintaining their high fully franked dividends. Additionally, their share prices are likely to see support over the next 12 months as the remediation and compliance charges stemming from the Royal Commission begin to abate. Commonwealth Bank and ANZ may conduct share buy-backs over the next year if the RBNZ adopts a more conciliatory capital strategy.

Hugh Dive is Chief Investment Officer of Atlas Funds Management. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

Additional Infographic, courtesy of KPMG