In finance, the excess return of a fund relative to a benchmark is called the alpha, and never has the competition for alpha been so intense. And it is just that: a competition. Ultimately, total alpha across the marketplace must equal zero on a gross (of all fees) basis. Investment banks are not charities and so net alpha is more negative on an after-transaction costs basis. There aren’t that many not-for-profit fund managers either, and their fees take another slice off aggregate alpha. While some negative alpha may be experienced by arguably less informed investors (commonly industry puts retail investors in this category, but perhaps this is not always the case), it is naïve to assume that the investment management industry has a licence to produce positive alpha.

Stricter judgement of ‘real alpha’

Historically in a world of passive funds and active funds, alpha was simply defined as the performance of an active fund against its market benchmark. Now we have around 25 years of academic literature behind us exploring how simple style factors such as value, size and momentum can explain stock portfolio returns (see Fama and French (1992) and Carhart (1997) for early seminal examples – www.scholar.google.com makes this easy).

Many of these factors are now being used to manufacture low cost product under various names such as smart beta and smart indexing. Consultants the world over, super funds and any quality institutional investor assess the performance of funds against a range of these benchmarks. In some cases this type of analysis (often simply regression-based) explains some of what may have been labelled as ‘alpha’.

Fierce competition for alpha

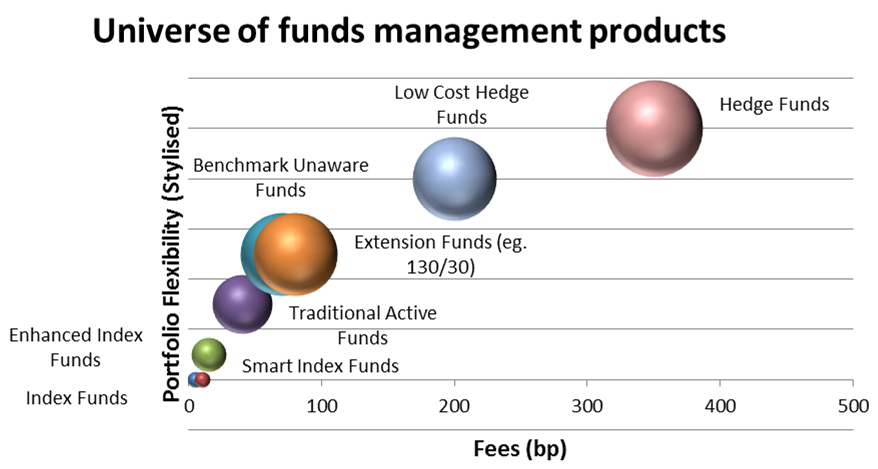

Where historically the universe of investment management products consisted of passive and active funds, today we have a broader spread of product. The competitors for alpha charge different levels of fees, have varying degrees of flexibility and take different amounts of active risk. This is all presented stylistically in the diagram below (with the size of the bubble being a proxy for the level of active risk).

The flexibility in some of these structures (for instance hedge funds are not benchmarked and can use a wide range of techniques such as leverage, short selling and derivatives) potentially provides an advantage. On the other hand a simple active traditional fund may keep life simple from a risk perspective and allow the manager to focus on idea generation.

And if the range of competitors was not enough, the degree of observation and analysis of a fund’s activities is greater than ever. We have asset consultants and other research groups as well as institutional investors all analysing how managers generate their returns. Nor are investment banks shy about trying to identify trading opportunities. It is easy to understand how proprietary trade ideas and process components get leaked across the market – many groups who analyse funds can be inadvertent disseminators of information. Consider the following innocent conversation:

Asset consultant to Fund Manager 1: What is your competitive edge?

Fund Manager 1: Well, we search hard for this particular characteristic (insert name) in the stocks that we purchase and it has worked well for us.

Asset consultant to Fund Manager 2: Do you search for this particular characteristic (insert name) when you are screening for stock ideas?

Fund Manager 2: No … but, um, it is in our research pipeline (… as he makes a note to himself).

I recall a US-based hedge fund we were invested with years ago who found a clause in some bond documentation that the market had overlooked. They placed some trades but in doing so the secret got out and they only made a marginal return for their efforts.

And don’t forget the academics: they play their part in identifying what they call ‘market anomalies’. They have their own competitive challenge: to produce research that extends the literature and is sufficiently insightful to get it published in top journals. This research is then available to the broader public, including fund managers. A paper by Bill Schwert from the University of Rochester, titled Anomalies and Market Efficiency (2002), identified that the returns from many market anomalies identified in academic literature deteriorated or even disappeared once the academic literature was published. This is reasonable: if the research is significant then it is being read by fund managers and investment banks and being incorporated into investment products. Indeed it is common, particularly in the US, to see many leading finance academics also working in industry.

Preserving the alpha edge

If a fund manager believes it has a true investment edge over the market then how can this be preserved and protected? Not easy but here are some considerations to look for:

- The competitive edge should be clearly defined. What is the foundation of the fund manager, what does it believe in? If that foundation feels like a general statement rather than something that is specific and well considered, then I would have doubts from the start.

- Continual self-assessment of the edge and performance. Has the market structure changed? Are there more managers thinking about the same thing? Does performance support their beliefs about alpha, accounting for the market environment? It is surprising how many fund managers do not assess their performance against a relative style index (e.g. a value manager should compare its performance against a value index).

- Ongoing process enhancement. A good example here is making the most of technological developments. It is impressive to see how many discretionary (where the analysis and decision is made by a person and not a computer) fund managers now use computer screening to help filter their universe down. They remain a discretionary fund but they are making good use of technology to keep them efficient.

- Diligence in managing fund capacity. Every strategy has a capacity limit before the alpha profile starts to decay. What I find interesting, and potentially flawed, is that many managers consider the capacity of their own fund without considering the capacity of their strategy as a whole, ignoring the size of other managers with similar strategies.

- Hard work and hiring and developing the right people are obviously key to success for any business.

For investors looking to construct portfolios of actively managed funds, the assumption of positive alpha across the portfolio is possibly a naïve one. And yet there is this magnetic attraction to invest actively – an extra layer of return compounds nicely through time. My advice is to make use of all the information available (including smart index data and research), invest across the entire universe of funds management products rather than just along product silos, and always invest pragmatically with the low cost solution being your default position.

David Bell is Chief Investment Officer at Mine Wealth + Wellbeing. He teaches the Hedge Funds elective for Macquarie University’s Master of Applied Finance and is studying towards a PhD at University of NSW.