The past four years have been quite turbulent for fixed income, an asset class that is generally characterised as defensive. An important question to ask is whether Government and other high-quality fixed rate bonds still have a role to play for Australian investors.

To answer that question, we must first ask, what is the purpose of bonds in a portfolio?

The role of bonds in a diversified portfolio

While priorities may differ from one investor to the next, in a diversified investment portfolio bonds play four different roles.

- Income/Return: As its name suggests, fixed income generates an income stream. Ideally this should be above the return on cash (you earn a premium for taking duration or interest rate risk) and the rate of inflation (you earn a real return).

- Defensiveness: A concept not easily measured, but relative to riskier assets like shares, we generally expect fixed rate bonds to experience fewer and smaller drawdowns, with falls recovered more quickly. The very nature of a bond means that high quality fixed income should also have a lower probability of a permanent loss of capital.

- Diversification: Bonds often exhibit low or negative correlation against shares (when shares go up, bond prices fall and vice versa). These diversification benefits can reduce the overall volatility of a portfolio that also contains risk assets.

- Liquidity: High grade bonds should be easily saleable and at little cost, which can provide a readily available source of funding when market opportunities arise.

On every one of those measures, Australian bonds have failed investors at some point since the onset of the pandemic.

The reality of the past few years

In 2020, when financial markets were concerned about pandemic induced stagnation and possible deflation, the yield on the Ausbond Australian Government Bond benchmark portfolio of Australian government bonds was as low as 0.6%[1] implying its forward-looking ability to provide income or return was negligible.

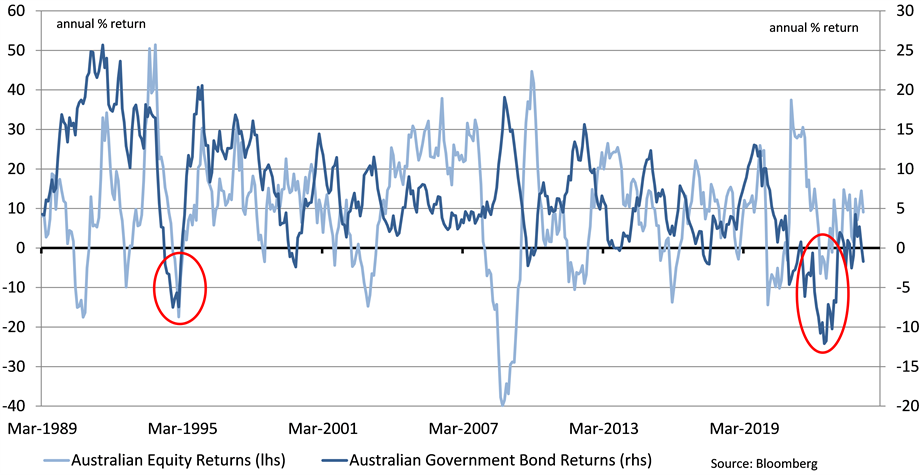

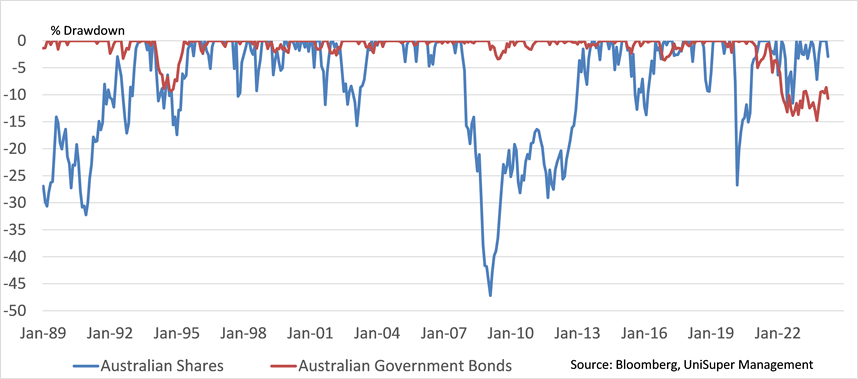

Between 2020 and its lows in 2023, as concerns transitioned towards excessive inflation amongst supply chain problems and strong labour markets, global central banks including the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) hiked rates aggressively and bond yields surged. The Australian Government Bond benchmark lost nearly 15% of its initial value[2] and more than four years since the onset of the pandemic is still 10% below its peak (chart 1). This marked the largest and longest lasting drawdown in bonds in decades.

Chart 1: Annual Returns of Australian Government Bonds vs Shares

The upshot of this is that bonds and shares have in recent years been positively rather than negatively correlated, which can reduce the diversification benefits of owning bonds as a hedge for shares. During 2022, as share markets faltered, bonds were even weaker and bond holdings compounded the loss for diversified investors (chart 2).

Chart 2: Drawdowns in Australian Government Bonds and Shares

The question remains then - looking forward, what benefit can we expect from holding high quality fixed rate bonds?

Well the good news is that the experience of recent years has set up a far better environment, both in respect of the prospective return income bonds can be expected to generate and the defensiveness that investors can expect from them.

Income and return expectations

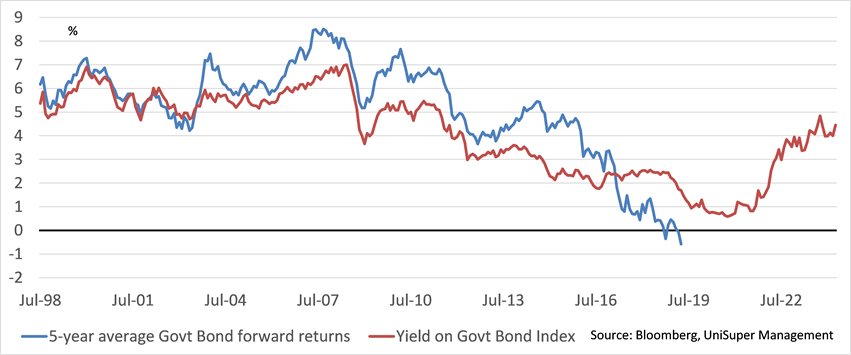

In terms of income expectations, a good starting point for annual average return expectations for a diversified portfolio of government bonds over a five-to-six-year horizon (which is the average maturity of the bonds), is the current yield of that portfolio.

Realised returns may differ from that initial yield depending on the movement in bond yields over the period.

Recall that bond prices move inversely to the yield so realised returns can be higher than the initial yield if yields have fallen. This is what occurred over the three decades leading up to the pandemic when yields were in long term structural decline.

In contrast realised returns can be lower than the initial yield if yields have risen which is what has occurred since the pandemic (chart 3).

Chart 3: Yield on Government Bond Index vs 5 year forward realised returns

The current yield on the Australian Government Bond benchmark is approximately 4.4%. This can be a good starting estimate for expected returns for a portfolio of Government bonds over coming years, though a large swing in bond yields in either direction would impact realised returns.

It’s important to note that while this yield is below current returns on cash and recent inflation outcomes, it does appear to represent a reasonable premium over the likely forward looking cash return (which we expect to be in a 3-4% range) and the expected rate of inflation (the RBA target is inflation of 2-3%).

How defensive are bonds right now?

In terms of defensiveness, you could argue that at higher starting yields, future drawdowns in bonds could once again be both less frequent and of smaller magnitude. This is because there is a higher income cushion to protect against price falls for a given increase in yields (chart 4).

Chart 4: Increase in yield required to eliminate income cushion on Government bonds

At the peak of the pandemic, when the yield on the Australian Government Bond benchmark was just 0.60%, just a 0.1% point increase in yields was enough to wipe out the income cushion for the year and deliver a negative return on bonds. Now that the starting yields of the benchmark portfolio is higher at 4.4%, it would take around 0.8% of an increase in yields to deplete the higher income cushion.

A higher starting yield can also impact the range of potential return outcomes looking ahead. Though it is plausible that yields could still move higher and deliver further drag on performance, there is less pressure to do so at a higher starting yield. Similarly, starting at a higher level of bond yields can also open up a greater potential for yields to fall in the event of a downturn in the economy, which can create the opportunity for price appreciation in bonds.

Will bonds regain their diversification benefits?

As highlighted earlier, the celebrated diversification benefits of bonds are at their maximum when bond returns exhibit negative correlation with equity returns i.e bond prices rise (or bond yields fall) when share prices fall.

Indeed, this has been the dominant experience of investors for most of the past 30 years and has contributed to the popularity of a diversified portfolio of shares and fixed rate bonds.

While the breakdown of this relationship in recent years might feel like the exception to the modern investor, over a broader sweep of history there are long periods where shares and bonds have been positively correlated.

So, in what circumstances are bond correlations positive and negative?

The experience of negative correlation of recent decades coincided with the introduction of inflation targeting central banks which helped keep inflation low and stable. Policymakers were assisted in keeping inflation low by globalisation, particularly the integration of China into global supply chains, technological advances, more flexible labour and product markets, economies that were more resilient to supply shocks and an unusually benign geopolitical backdrop. In this environment, the main driver of financial markets was economic growth. When growth trends dictate financial market moves, shares and bonds move in different directions. An improvement in growth is good for shares but bad for bonds as interest rates move higher and vice versa.

Positive correlation in contrast occurs when economic developments push shares and bonds in the same direction. Historically there are two situations in which this can arise:

- When a sovereign becomes so deeply indebted that the perceived credit worthiness of the government is exacerbated by weak growth. This is the situation that the Italian Government found itself in for about a decade after the Global Financial Crisis.

- When inflation is high and there is increased uncertainty as to whether it can be contained. This has been the environment since the onset of the pandemic. In an environment when inflation is the dominant driver of policy making and interest rates rise potentially at the cost of economic growth, this pushes share prices and bond prices in the same direction.

Given that the Australian Government maintains very low debt, the former situation is unlikely. However, it is far from assured that Australia will return to the low and stable inflation environment of the preceding three decades.

There are a few reasons for this: Governments around the world seem more comfortable with fiscal excess, globalisation has given way to deglobalisation and a more fractured supply chain, a falling proportion of working age population and higher dependency will reduce the availability of labour relative to demand. Climate change leading to more extreme weather and supply shortages will make the cost of food and transportation more variable, and the cost of funding the energy transition, may also lead to higher energy prices.

Looking forward, while there will be periods, such as in a growth shock, that bonds and shares will move in opposite directions. Investors need to be aware that there will likely be more frequent periods where bonds and shares move in the same direction, reducing the diversification benefit that bonds provide.

Final comments

In our view high grade fixed rate bonds can offer a reasonable prospect of return in excess of both inflation and cash and are likely do so with fewer and smaller drawdowns that are recovered more quickly. But bonds are unlikely to deliver the outsized returns that we saw over the three decades leading up to the pandemic, and we can expect more frequent periods where bonds move in the same direction as shares.

David Colosimo hosts UniSuper’s monthly investment podcast (SuperInformed Radio) talking about what’s happening in the economy and investment markets. Subscribe and find all previous episodes via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, SoundCloud, or wherever you get your podcasts. UniSuper, a sponsor of Firstlinks.

Please note that past performance isn’t an indicator of future performance. The information in this article is of a general nature and may include general advice. It doesn’t take into account your personal financial situation, needs or objectives. Before making any investment decision, you should consider your circumstances, the PDS and TMD relevant to you, and whether to consult a qualified financial adviser.

[1] September 2020

[2] November 2020 to June 2022