This is an edited transcript of an interview between Stanford Brown CEO Vincent O'Neill and former RBA Governor and Stanford Brown Investment Committee member Ian Macfarlane on 6 November, 2023.

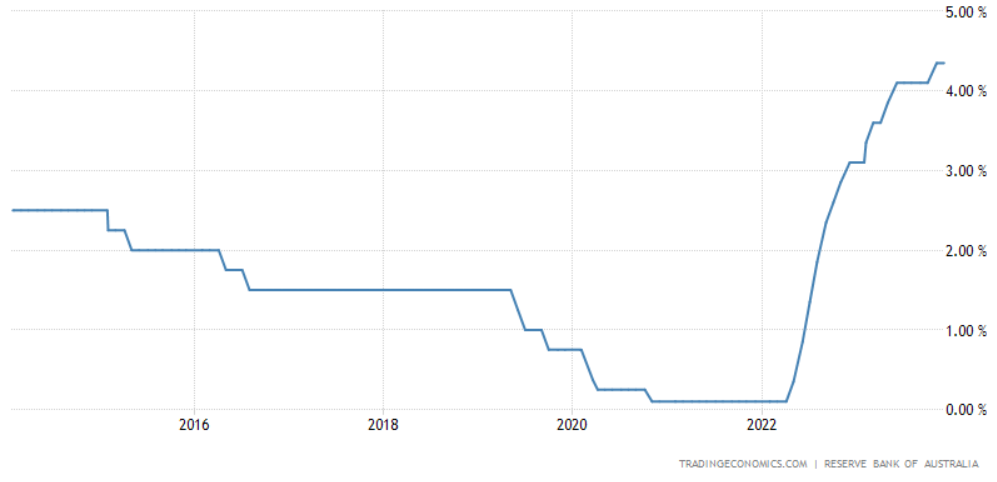

Vincent O'Neill: Ian, we've met on this podcast a few times over the last 18 months or so and I'd like to start today if we can, given the significant interest rate increases that we have seen in the past 18 months, where do you now see that we're at in the cycle?

Macfarlane: Well, the economy has slowed as you would expect but it hasn't slowed as much as most people would have expected. I mean there are some puzzles out there. I think a year ago, if you had been told that interest rates would be raised by 400 basis points, you wouldn't expect the unemployment rate to still be at multiple decade lows. And I think the other thing you wouldn't expect, you wouldn't expect to see house prices having risen for the last six months.

So, why has there not been a bigger contraction? Well, the first thing I think is even though the change from 0% to 4% is a big change, the level of interest rates at 4%, that's not a very high level of interest rates. That's actually below average.

O'Neill: In terms of the historical long term.

Macfarlane: Yeah, absolutely. And the economy can operate perfectly well with a level of interest rates – the risk-free rate, the overnight cash rate at 4%. It never got down to 4% in the 10 years that I was a governor.

Australia interest rates

O'Neill: Do you think that's a surprise to many people that we've been able to wear the increase that we have to-date with that more significant economic fallout?

Macfarlane: Yeah, I think it has been a surprise to everyone. So, that's the first thing. You've got to sometimes think in terms of level, not just changes. The second thing is although monetary policy has a number of effects, in Australia its biggest single effect is actually through the mortgage market and through indebted households, and there's no doubt that a lot of those have been squeezed. But that's only part of the economy. There's a lot of other parts that are just soldiering on as normal. The corporate sector in Australia is not highly geared. They've felt a bit of a pinch but not much. The resource sector is doing well. Agriculture is doing well. And if you try and book an upmarket restaurant midweek, you'll discover that there's an awful lot of people out there who are still living very comfortably.

O'Neill: And spending.

Macfarlane: And spending, yes. So, the bottom end of town has been squeezed and the top end of town has not been squeezed very much at all. And finally, the other thing that is new which had to be factored in, we hadn't seen it before, which is this huge increase in population. 450,000 over the last recorded 12-month period, we think the next 12 when we move ahead a quarter it's going to be 500,000. That's a huge amount. I mean, typically, it was 200,000 a year and at an extreme 300,000 but never had 500,000. The other amazing thing is this huge increase in population and they're all finding jobs. So, I don't want to give the impression that the economy is so resilient that nothing is going to happen. I think there will be further contraction. And we also got to remember that over the last two completed quarters although GDP grew, it grew less than population and that's very unusual.

O'Neill: So, people describe the per capita recession potentially.

Macfarlane: Yeah, I haven't heard that used before, but it is unusual.

O'Neill: And probably – you haven't heard it much before because you probably haven't had that degree of immigration in such a short timeframe given I guess the post-COVID catch-up that we've had. Now I'm conscious as we record this morning, we're just over 24 hours out from the next RBA meeting and the decision there. I'm not going to ask you to make a call on that one, but I would ask what is your broader outlook for rates given the rate of increase, how far we've come, but the resilience that we're still seeing in the economy?

Macfarlane: Well, I think you just made the case in your question for the position that is far more likely to be increases than for it to be steady over the next year and certainly far more likely to be increases or steady than for it to fall.

O'Neill: What's your views in terms of what you see in the inflation picture?

Macfarlane: Well, the thing that will really determine the outcome is what's happening to inflation. We had some comprehensive figures on inflation came out a couple of weeks ago. There's no such thing as the official inflation rate. You have to actually look at all the different measures over all the different time periods – monthly, quarterly, six monthly, 12 months ended. You have to look at headline inflation. You have to look at core inflation. My reading of all those numbers is really whatever you do with a rate of inflation still got a 5 in front of it. So, it's come down a bit as some of the transitory factors have washed out but still are about 5. It's probably got further to come down, but I wouldn't be holding my breath. I think it will happen slowly. The Reserve Bank forecast, I wouldn't call it a forecast, I'd call it an assumption, is that it won't get to below 3 until the second half of 2025. I think that's a reasonable assumption whether it happens or not, I don't know. But it's a reasonable assumption at this point, in which case, you wouldn't be expecting interest rates to come down if that's the outlook.

Australia inflation rates

O'Neill: Anytime soon. But you say that, and we've got the money market still forecasting a reduction in the cash rate potentially even in the second half of next year. How do you balance those two factors?

Macfarlane: Well, the money market always does that. I mean, you can work out what the money market is expecting for the cash rate from this thing called the short-term yield curve and it's constantly expecting in a very short-term an increase and then within a year interest rates to start coming down again. In other words, they're expecting the anti-inflation job to be completed within a year.

O'Neill: To have almost instantaneous impact of those increases.

Macfarlane: Yeah. And of course, they've been wrong every time, and I think they're still wrong. I mean, the only way I could conceive of that eventuality of interest rates coming down within the year would be if inflation got down to below 3% within a year. I don't think that's going to happen. I don't think anybody thinks that's going to happen. Or if there was going to be a sharp recession with a big jump in unemployment, and I don't think that's going to happen either.

O'Neill: Again, the economy is showing a lot more resilience. It would have to be a big correction for that to play out. So, you look at those outcomes and you expect monetary policy essentially to play out in slow motion.

Macfarlane: Yes, I think so.

O'Neill: I'd like to talk, if we can, about the transitioning governor from Phil Lowe to Michele Bullock. From your seat, given your experience, should we expect anything different?

Macfarlane: I don't think the change in personalities will make a big difference. I know both of them well. They both worked for me for a long time. But what could make a very big difference is if the proposals in the review of the Reserve Bank are carried out, that will make a very big difference, and it will lead to a much inferior monetary policy than we've had over the previous 30 years.

O'Neill: You're talking about an environment there where it's much tougher for Michelle Bullock to potentially operate than the environment under which you operated?

Macfarlane: Yeah, I think Michelle Bullock will have a much harder job than any of her predecessors and any of her peer governors in other countries if these proposals go through.

O'Neill: For the benefit of the listeners who are less familiar with the proposed changes, do you mind setting out the most substantive element of what has been discussed?

Macfarlane: Well, the main change will be to reduce the power of the governor and transfer that power to the part-time members of the board. Now, the Reserve Bank Board has nine members. Reserve Bank represents two of those and seven of them are outside the Reserve Bank. And it's operated, I think, reasonably well because it is operated as an advisory board or like a corporate board. But the proposals are to turn it from being like that type of board into a decision-making board where at each meeting the decision has to be voted on, has to be recorded, and has to be published. So, what this means is that the outsiders or the part-timers on the Reserve Bank Board will have the majority of the voting power.

O'Neill: Will have the balance of power.

Macfarlane: They'll have more. They'll have – they've seven out of nine, one of whom is the Secretary of the Treasury and six are part-timers who are supposed to work one day a week. But they will have two-thirds of the voting power on monetary policy. So, that's what's going to make the governor's position very difficult.

This is an edited transcript of an interview between Stanford Brown CEO Vincent O'Neill and former RBA Governor and Stanford Brown Investment Committee member Ian Macfarlane on 6 November, 2023.