The Future of Financial Advice, or FoFA, reforms came into effect on 1 July 2013. They imposed a ban on conflicted remuneration and required financial advisers to act in the best interests of their clients. Existing commission arrangements were grandfathered, and looked like staying until the Financial Services Royal Commission tore them down.

This week, the final nail was hammered into the grandfathering coffin. The Treasury Laws Amendment (Ending Grandfathered Conflicted Remuneration) Bill 2019 passed in the House, banning conflicted remuneration paid to financial advisers from 1 January 2021.

However, the advice industry has not found another business model that allows average Australians to receive comprehensive financial advice. It is right that conflicted advice should be stamped out, but if most people now cannot access detailed and personal services, then we have fixed one problem and created another.

Why is full-service advice expensive?

I recently asked a financial adviser who services older, high-end clients about her first question at an initial meeting. “Tell me about your family,” she replied. Not money or assets, but a person talking to a person about their family, life and goals. And there is the affordability dilemma. Comprehensive financial advice takes a lot of time. A full Statement of Advice (SOA) runs over 100 pages and the need to review all circumstances and develop a plan takes 10 to 15 hours and costs between $3,000 and $5,000 depending on complexity.

But focussing only on the SOA overlooks a bigger point. There is far more to a comprehensive relationship than an initial document. The Financial Planning Association (FPA) identifies six steps in the advice process:

- Defining the scope of the engagement

- Identifying the goals

- Assessing the financial situation

- Preparing the financial plan

- Implementing the recommendations

- Reviewing the plan

An added complication is that most financial planners offer an initial meeting for free. Business development takes a lot of time and expertise. The adviser must write a proposal to a potential client stating how much the advice will cost and what will be involved without knowing if the client will pay. It's often a loss lead to win the business.

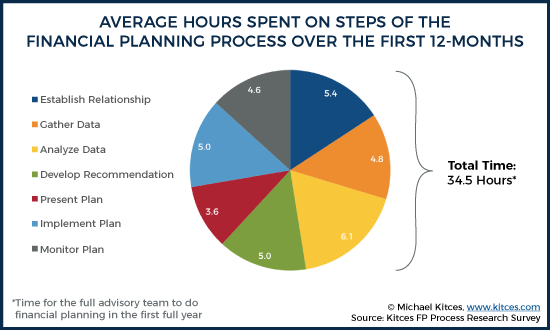

The first year of working with a client takes more like 35 hours which limits the number of clients a new adviser can accept. The cost of 35 hours at $300 an hour is about $10,000. A financial advice group that charges an ongoing fee of 1% of the portfolio (usually a declining percentage for large balances) requires $1 million to earn $10,000 for full-service advice. Most people do not have $1 million. Other groups are moving to a charge a percentage of income as the advice work is more labour intensive.

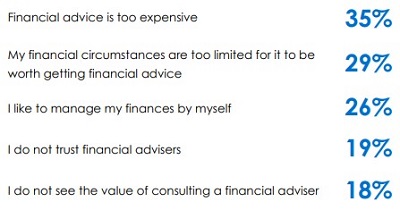

The recent ASIC survey results in ‘Financial advice: what consumers really think’ found:

“Perceiving financial advice as too expensive was the most commonly identified reason for not seeking advice. Overall, 64% of all the online survey participants agreed that financial advisers were too expensive.”

The most common reasons for not seeking advice were (multiple answers allowed):

Metlife recently reported it costs $5,000 for an adviser to complete a risk insurance plan, but consumers are willing to pay only about $1,200 in up-front fees. A leading boutique advice CEO told me their minimum fee is $6,000 a year, and this gives only a basic service of one meeting a year. Another CEO said high touch is now reserved for clients with over $2 million, mid touch is from $750,000 to $2 million and low touch is sub $750,000.

At the latest Association of Financial Advisers’ National Conference, EQ Wealth Director Simone Du Chesne, said:

“I find it incredibly ironic that accessing financial advice has become the privilege of the middle class and that those who may need it most or just as much as any other Australian are not able to afford to see an adviser … While I appreciate and support the need for operating in a compliant manner when providing advice, I believe the paperwork has become onerous.”

It’s one of many consequences of the Financial Services Royal Commission. It identified the problem of conflicted remuneration without providing a mass market solution.

Producing a financial plan

A 2018 FPA survey of its members found the average cost for an initial SOA was $2,435. The average ongoing fee was $3,354 per annum, taking the average cost to almost $6,000 in the first year. Of course, there was a wide range.

Some advice firms are managing compliance by treating clients as ‘wholesale’, which removes the need to provide an SOA for a 'retail' client.

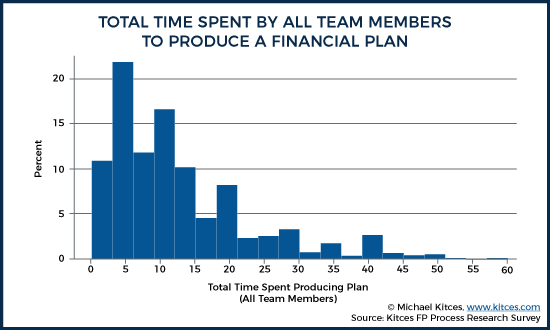

Kitces Research in the US has studied how long financial planning takes. I will assume the numbers are similar in Australia because there’s little to suggest our regime is less onerous. Ask any financial adviser what they must do with a new client and their eyes will roll as they think about compliance, legal, best interests duty, conflicts, etc.

The Kitces article ‘How Financial Advisers Actually Do Financial Planning’ provides details on how long they work and what they do. Notably, only 19% of time is spent meeting clients with 17% spent on business development. The most time-consuming part is designing financial plans and preparing for meetings with clients.

The following chart on time spent to produce a financial plan shows a median of 10 hours, but an average of 15 hours with a long tail due to some complex and time-intensive plans.

Similar to the FPA model, Kitces identifies seven steps involved in the first year of a relationship, and the chart below shows how this can consume the best part of a working week. On one client. In addition to these steps, depending on the structure of the adviser business, a good chunk of extra time is taken simply running the business. It doesn’t leave much space for other new clients, which is another reason the industry believes there will be a shortage of advisers as education standards hit in coming years.

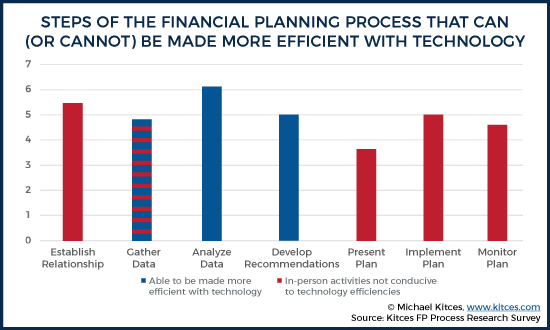

How much will technology assist?

Surely, this is where adviser technology and software come in. Here is Kitces’ most significant insight. The majority of the financial planning process involves client meetings and activities which technology has limited scope to replace. In the following chart, only the blue steps can be made more efficient with technology, and there’s a lot more red.

The steps of gathering and analysing data and developing recommendations are number-crunching processes which technology can improve. It can’t help much with client conversations, discovery of goals, a deep understanding of risk appetite beyond some simple tests, and coaching the client in how to use a new plan. This is person-to-person stuff.

The ASIC regtech solutions symposium

I recently attended an ASIC Regtech Financial Advice Files Symposium where providers of ‘regtech’ solutions were challenged to:

“Demonstrate how technology can be used to help in determining the level of risk and regulatory compliance of financial advice based on a sample of client files in different formats provided by ASIC and any wider sample of client files or other related client profile and transactional data obtained independently by demonstrators.”

The six providers were Tiqk, GIRO by K&L Gates, IRESS, IBM, Flexprod and Advice Regtech.

Some impressive progress has been made in improving the efficiency of reviewing documentation for regulatory compliance, and it fits in well with Kitces’ argument that certain parts of the advice chain can be improved by technology.

My brief summary of how regtech works for client advice files is that the technology scans the words and tables in financial advice documents to check for compliance with company policies, consumer obligations and best interest duty regulations. It aims to make internal compliance more efficient by flagging shortcomings against a series of lists. For example, it flags high-risk portfolios for extra review and scans for key words. It checks every file instead of the usual sample taken for audit purposes. Risk monitoring is improved with greater efficiency than the labour-intensive and error-prone exercise of humans scanning files.

At this stage of its development, it’s only the start of a machine-learning and AI journey that makes marginal improvements in efficiencies. It is confined to checking and monitoring but this is a minority of the time spent by an adviser on a comprehensive plan. Anyone thinking regtech will fundamentally change the comprehensive advice process is in for a long wait.

As Daniel Crennan QC, Deputy Chair at ASIC, said in the introduction:

“In order to improve risk management and minimise your compliance risks, you must include the capacity to explore, test, and implement ‘compliance-by-design’ regtech solutions within your business model. Obviously, none of us know what the future holds in this space. It’s a learning exercise and none of us can doubt that technology is front-and-centre of financial services provision ... it would be ideal to witness a decrease in the number of ASIC’s compliance-related enforcement actions as a direct result of industry’s uptake of regtech.”

'Advisertech' is not limited to regtech, and other tools that might help advisers include enhanced financial planning software, the design of the investment platform, customer risk management and other office management tools.

What about digital advice (robo-advice)?

This is not the place for a full review of Australian robo-advice, and we have covered the subject before, such as here. The ASIC survey said:

- Only 1% of participants had used digital advice.

- 19% said they were open to it, once it was explained to them.

Digital advice is more accurately digital investing, matching an assessed risk appetite with a simple, diversified portfolio. There is a role for digital advice with inexpensive model portfolios matched to some measure of risk, that are easy to implement for certain clients. In fact, it’s not dissimilar to the default option in a retail or industry superannuation fund, and costs about the same. Most Australians have a diversified fund at a cost of 60 to 100 basis points (0.6% to 1.0%) with access to a website, tax reporting and general advice.

But it’s not comprehensive financial advice. It can’t tell someone if they should invest or pay off their mortgage. It does not consider social security, super contributions, pensions, estate planning, insurance and a range of other issues good advisers now specialise in such as goals-planning and lifestyle coaching.

The leading robo-advice businesses in the world have morphed into a hybrid model that includes contact with humans. Vanguard’s Personal Advisor employs 800 financial advisers. At its heart, financial advice involves learning the goals and dreams of a client and coaching them in their unique circumstances, and most people want these discussions with an empathetic human.

Where is the advice industry heading?

Full-service financial advisers with high net worth clients will continue to have strong businesses. Their clients are willing to pay, and if comprehensive advice costs at least $10,000 as outlined by Kitces and the FPA, financial advice will increasingly become the domain of middle to upper income earners. At some stage, technology might offer better solutions but if regtech progress is any guide, it's in the early stages of delivering marginal efficiency improvements.

For all the criticism by the Financial Services Royal Commission, much of it deserved, the vertical integration model where advisers were allowed to use in-house products, had the potential to serve the mass market. I explained here how it could have worked, but the horse has bolted.

AMP’s decisions on the future of its financial advice business point some of the way. In the face of the devastating blows from the Royal Commission, their commission-driven model is being dismantled. They can no longer provide comprehensive advice to most Australians. AMP will develop a model similar to industry funds which provides intra-fund advice without a comprehensive SOA. At the lower asset levels, the first touch will be a call centre or digital offer that will not be detailed financial advice and not seek to understand everything about the client.

It would be a mistake to underestimate where AI and machine learning may take the advice industry. Algorithms may one day listen to conversations and recommend a portfolio. Data should be easier to collect through sophisticated online registries and aggregation portals. Investment management is falling in price. However, most of the required automation is years away at best. In the meantime, the full-service offer will be reserved for the top tiers of clients willing and able to pay.

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Cuffelinks. The charts from Michael Kitces are used here with his permission and are taken from this article, which gives more detail on his methodology.