(Substantial parts of this article were published last week. We are running it again with feedback from Adam Curtis of Perpetual, plus readers may have missed the insights from many financial advisers in the comments section).

The Future of Financial Advice, or FoFA, reforms came into effect on 1 July 2013. They imposed a ban on conflicted remuneration and required financial advisers to act in the best interests of their clients. Existing commission arrangements were grandfathered, and looked like staying until the Financial Services Royal Commission tore them down.

This week, the final nail was hammered into the grandfathering coffin. The Treasury Laws Amendment (Ending Grandfathered Conflicted Remuneration) Bill 2019 passed in the House, banning conflicted remuneration paid to financial advisers from 1 January 2021.

However, the advice industry has not found another business model that allows average Australians to receive comprehensive financial advice. It is right that conflicted advice should be stamped out, but if most people now cannot access detailed and personal services, then we have fixed one problem and created another.

Why is full-service advice expensive?

I recently asked a financial adviser who services older, high-end clients about her first question at an initial meeting. “Tell me about your family,” she replied. Not money or assets, but a person talking to a person about their family, life and goals. And there is the affordability dilemma. Comprehensive financial advice takes a lot of time. A full Statement of Advice (SOA) runs over 100 pages and the need to review all circumstances and develop a plan takes 10 to 15 hours and costs between $3,000 and $5,000 depending on complexity.

But focussing only on the SOA overlooks a bigger point. There is far more to a comprehensive relationship than an initial document. The Financial Planning Association (FPA) identifies six steps in the advice process:

- Defining the scope of the engagement

- Identifying the goals

- Assessing the financial situation

- Preparing the financial plan

- Implementing the recommendations

- Reviewing the plan

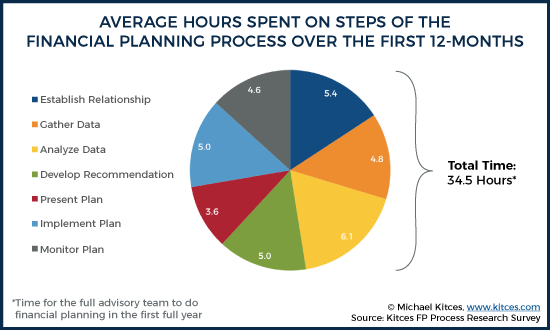

The first year of working with a client takes more like 35 hours which limits the number of clients a new adviser can accept. The cost of 35 hours at $300 an hour is about $10,000. A financial advice group that charges an ongoing fee of 1% of the portfolio (usually a declining percentage for large balances) requires $1 million to earn $10,000 for full-service advice. Most people do not have $1 million. Other groups are moving to a charge a percentage of income as the advice work is more labour intensive.

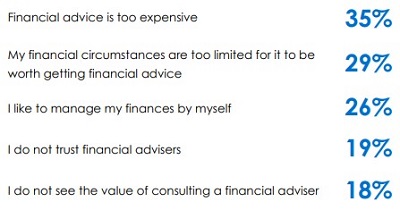

The recent ASIC survey results in ‘Financial advice: what consumers really think’ found:

“Perceiving financial advice as too expensive was the most commonly identified reason for not seeking advice. Overall, 64% of all the online survey participants agreed that financial advisers were too expensive.”

The most common reasons for not seeking advice were (multiple answers allowed):

Metlife recently reported it costs $5,000 for an adviser to complete a risk insurance plan, but consumers are willing to pay only about $1,200 in up-front fees. A leading boutique advice CEO told me their minimum fee is $6,000 a year, and this gives only a basic service of one meeting a year. Another CEO said high touch is now reserved for clients with over $2 million, mid touch is from $750,000 to $2 million and low touch is sub $750,000.

At the latest Association of Financial Advisers’ National Conference, EQ Wealth Director Simone Du Chesne, said:

“I find it incredibly ironic that accessing financial advice has become the privilege of the middle class and that those who may need it most or just as much as any other Australian are not able to afford to see an adviser … While I appreciate and support the need for operating in a compliant manner when providing advice, I believe the paperwork has become onerous.”

It’s one of many consequences of the Financial Services Royal Commission. It identified the problem of conflicted remuneration without providing a mass market solution.

Producing a financial plan

A 2018 FPA survey of its members found the average cost for an initial SOA was $2,435. The average ongoing fee was $3,354 per annum, taking the average cost to almost $6,000 in the first year. Of course, there was a wide range.

Some advice firms are managing compliance by treating clients as ‘wholesale’, which removes the need to provide an SOA for a 'retail' client.

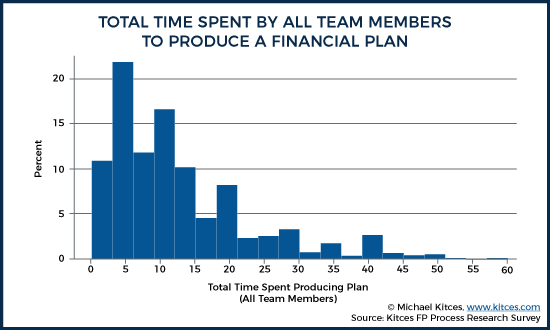

Kitces Research in the US has studied how long financial planning takes. I will assume the numbers are similar in Australia because there’s little to suggest our regime is less onerous. Ask any financial adviser what they must do with a new client and their eyes will roll as they think about compliance, legal, best interests duty, conflicts, etc.

The Kitces article ‘How Financial Advisers Actually Do Financial Planning’ provides details on how long they work and what they do. Notably, only 19% of time is spent meeting clients with 17% spent on business development. The most time-consuming part is designing financial plans and preparing for meetings with clients.

The following chart on time spent to produce a financial plan shows a median of 10 hours, but an average of 15 hours with a long tail due to some complex and time-intensive plans.

Similar to the FPA model, Kitces identifies seven steps involved in the first year of a relationship, and the chart below shows how this can consume the best part of a working week. On one client. In addition to these steps, depending on the structure of the adviser business, a good chunk of extra time is taken simply running the business. It doesn’t leave much space for other new clients, which is another reason the industry believes there will be a shortage of advisers as education standards hit in coming years.

How much will technology assist?

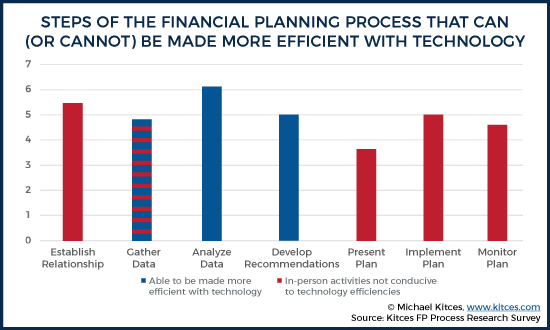

Surely, this is where adviser technology and software come in. Here is Kitces’ most significant insight. The majority of the financial planning process involves client meetings and activities which technology has limited scope to replace. In the following chart, only the blue steps can be made more efficient with technology, and there’s a lot more red.

The steps of gathering and analysing data and developing recommendations are number-crunching processes which technology can improve. It can’t help much with client conversations, discovery of goals, a deep understanding of risk appetite beyond some simple tests, and coaching the client in how to use a new plan. This is person-to-person stuff.

ASIC 'advisertech' and 'regtech'

At a recent ASIC Regtech Financial Advice Files Symposium, providers of ‘regtech’ solutions were challenged to:

“Demonstrate how technology can be used to help in determining the level of risk and regulatory compliance of financial advice based on a sample of client files in different formats provided by ASIC and any wider sample of client files or other related client profile and transactional data obtained independently by demonstrators.”

The six providers were Tiqk, GIRO by K&L Gates, IRESS, IBM, Flexprod and Advice Regtech.

Some impressive progress has been made in improving the efficiency of reviewing documentation for regulatory compliance, and it fits in well with Kitces’ argument that certain parts of the advice chain can be improved by technology.

My brief summary of how regtech works for client advice files is that the technology scans the words and tables in financial advice documents to check for compliance with company policies, consumer obligations and best interest duty regulations. It aims to make internal compliance more efficient by flagging shortcomings against a series of lists. For example, it flags high-risk portfolios for extra review and scans for key words. It checks every file instead of the usual sample taken for audit purposes. Risk monitoring is improved with greater efficiency than the labour-intensive and error-prone exercise of humans scanning files.

At this stage of its development, it’s only the start of a machine-learning and AI journey that makes marginal improvements in efficiencies. It is confined to checking and monitoring but this is a minority of the time spent by an adviser on a comprehensive plan. Anyone thinking regtech will fundamentally change the comprehensive advice process is in for a long wait.

As Daniel Crennan QC, Deputy Chair at ASIC, said in the introduction:

“In order to improve risk management and minimise your compliance risks, you must include the capacity to explore, test, and implement ‘compliance-by-design’ regtech solutions within your business model. Obviously, none of us know what the future holds in this space. It’s a learning exercise and none of us can doubt that technology is front-and-centre of financial services provision ... it would be ideal to witness a decrease in the number of ASIC’s compliance-related enforcement actions as a direct result of industry’s uptake of regtech.”

'Advisertech' is not limited to regtech, and other tools that might help advisers include enhanced financial planning software, the design of the investment platform, customer risk management and other office management tools.

Where is the advice industry heading?

Full-service financial advisers with high net worth clients will continue to have strong businesses. Their clients are willing to pay, and if comprehensive advice costs at least $10,000 as outlined by Kitces and the FPA, financial advice will increasingly become the domain of middle to upper income earners. At some stage, technology might offer better solutions but if regtech progress is any guide, it's in the early stages of delivering marginal efficiency improvements.

For all the criticism by the Financial Services Royal Commission, much of it deserved, the vertical integration model where advisers were allowed to use in-house products, had the potential to serve the mass market. I explained here how it could have worked, but the horse has bolted.

AMP’s decisions on the future of its financial advice business point some of the way. In the face of the devastating blows from the Royal Commission, their commission-driven model is being dismantled. They can no longer provide comprehensive advice to most Australians. AMP will develop a model similar to industry funds which provides intra-fund advice without a comprehensive SOA. At the lower asset levels, the first touch will be a call centre or digital offer that will not be detailed financial advice and not seek to understand everything about the client.

It would be a mistake to underestimate where AI and machine learning may take the advice industry. Algorithms may one day listen to conversations and recommend a portfolio. Data should be easier to collect through sophisticated online registries and aggregation portals. Investment management is falling in price. However, most of the required automation is years away at best. In the meantime, the full-service offer will be reserved for the top tiers of clients willing and able to pay.

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Cuffelinks. The charts from Michael Kitces are used here with his permission and are taken from this article, which gives more detail on his methodology.

Additional comments on 'unintended consequences' by Adam Curtis, Head of Investment Specialists, Perpetual Investments

Hi Graham,

I wanted to write you a short note essentially to flag how I really did enjoy your recent article in Cuffelinks 11 Sept re FOFA implications for Financial Advice.

I share many common views with you on what are some unfortunate and potentially unintended consequences relating to Financial Advice post RC. I’ve been thinking and reflecting on it a fair bit of late and your recent article I thought surmised it very well.

Life is full of unintended consequences but unfortunately I lament the brand damage the industry broadly has suffered. The actions of a few can destroy the brand of many. Whilst I am proud to work at Perpetual, I am even prouder to work in financial services, an industry that I consider plays an important and vital role in securing the future for many Australians. I know and have witnessed the value that quality fiduciary advice provides and the benefits that so many people receive from these services but unfortunately, in the short term, the brand of many can suffer due to the actions of a few.

Ultimately it serves a social purpose with many community benefits yet are we potentially at risk of unintended consequences despite best intentions, stemming from the RC and/or FOFA at least in the short term?

Surely the intention of this Commission and its recommendations is to ensure advice is of a high quality, advice is available, and advice is affordable yet for many reasons, perhaps less advice will be provided. Will those that need it be able to afford it or even seek it?

I don’t know how it will all play out but I did enjoy reading the article – I’m sure good advisers will ultimately prosper and many will benefit from their advice but in the short term there is pain and risk.

I recently presented on some of these thoughts of mine, personal and professional – it was wrapped around the concept of Unintended Consequences. I always like a good story and always look for metaphors in history.

Here's an example.

As we are all very familiar with, in 1912, The Titanic sunk and the huge loss of life, spurred a number of reviews and inquires, the largest of which was conducted by a US Senate Inquiry. It concluded, entirely reasonably, that the death toll would have been substantially lower if the Titanic had set to sea with a full complement of lifeboats. New regulations were developed for the ship building industry, existing boats were retrofitted to carry more lifeboats and new ships were redesigned to accommodate more.

One of the first ships to sail after this new regulation was the SS Eastland. On July 1915, just yards from her moorings on the Chicago River, she tilted alarmingly, took on water, and rolled over in just twenty-feet of water. While some lucky survivors were able to literally step from the upturned hull onto dry land, many less fortunate individuals were trapped below decks or thrown into the water. More than 800 people lost their lives. While the poor design of the ship and the owners’ failure to carry out tests were also to blame, it was the extra weight of the lifeboats that ultimately caused the Eastland to sink.

Despite the best intentions of the senators and regulators, at least in the short term, they created an industry with unfortunate and definitely unintended consequences

This story resonated with me. When I saw the article I did want to get in touch.

Regards, Adam Curtis