Australia’s economy has fared better than most post-GFC, buoyed primarily by the tail end of the resource boom, solid population growth and a strong financial sector. That said, with the resource boom maturing and the workforce ageing, the Australian economy has slowed – and is likely to grow at a slower pace in coming years than we’ve grown accustomed to. Investors must deal with the challenges of ‘picking winners’ in the new environment.

At first glance these changes could be taken as a negative for investors in the Australian share market. But the reality is that our economy has long had to cope with structural change, which has not stopped quality Australian companies from generating profits and wealth for investors over the long term.

Structural change and the economy

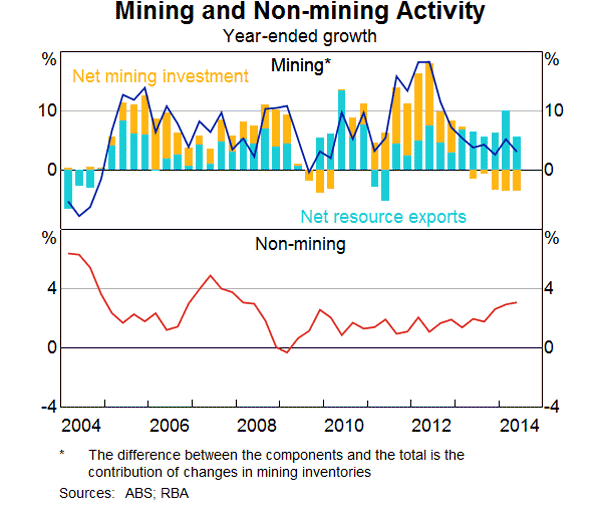

Most investors are familiar with Australia’s recent commodity export price boom, and the associated strong lift in mining investment. During this period, national income and employment grew at a healthy pace.

Of course, a by-product has been relatively high interest rates by global standards and a strongly rising Australian dollar, which have been harmful for many Australian sectors not exposed to the resource sector. In effect, interest rates and the $A worked to ‘squeeze’ other sectors of the economy to make room for a rapidly expanding resource sector without threatening a break-out in wages and prices.

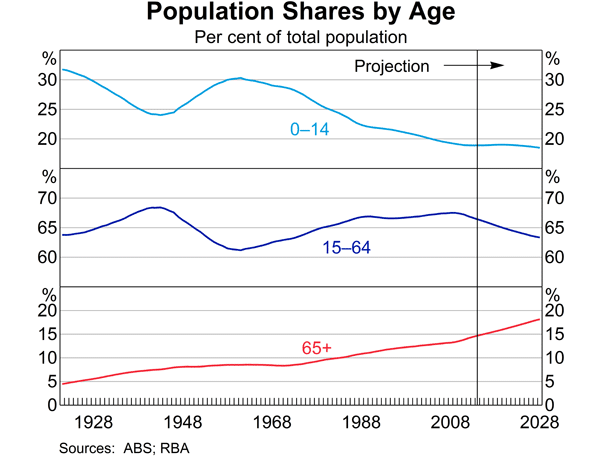

Population ageing has also contributed to a fall in labour force participation, which has meant somewhat slower growth in the work force relative to the overall population.

With commodity prices now in retreat, and a falling share of the population of working age, the Australian economy faces slower growth in national income. Indeed, Senior Treasury official Dr David Gruen recently noted gross national income per person grew at an annual rate of 2.3% over the past 13 years but may rise annually by only 0.9% over the next decade.

Reserve Bank Deputy Governor Philip Lowe extrapolates that data to suggest: “we will need to adjust to some combination of slower growth in real wages, slower growth in profits, smaller gains in asset prices and slower growth in government revenues and services.”

The economy’s next phase

The good news, however, is that slower income growth does not necessarily mean falling share prices or lower dividends. For starters, although growth in national income ‘per person’ may be slowing, overall growth in national income should remain well supported by continued solid population growth.

And growth in domestic production should be faster still, due to strong gains in resource export volumes – particularly iron ore and LNG – following the heavy investment in new capacity in recent years. Low interest rates and the weaker $A are also helping the economy unleash activity in sectors once held back by the mining boom, such as housing and non-mining trade exposed sectors like tourism and international education.

Of course, as the baby boomer generation moves into retirement, growth patterns will change. Far-sighted management should identify and respond to these changes – witness the massive investment by our major banks into wealth management businesses, to replace lost mortgage income with the fees earned by managing retirement funds.

More generally, the predicted changes in the economy should be gradual enough for many existing firms to respond in a timely manner to the new challenges and opportunities as they arise. And those that don’t are likely to be usurped by nimble new starters which, if successful, are also likely to stake their place among Australian listed companies.

Apart from changing or amending corporate strategy (which the best companies already do), astute management can also modify their financial management to maintain or boost dividends. Capital management programs can help support share prices and grow dividends, at least in the near to medium term.

In short, thanks to earlier pro-competitive reforms such as deregulation of labour and product markets and the floating of the $A, the Australian economy has demonstrated remarkable resilience and flexibility. It avoided recession over the past 20 years despite the dotcom crash, Asian financial crisis, and the most recent US sub-prime induced global financial crisis.

Picking winners will not be easy

We should not underestimate the ability of corporate Australia to rise to the next set of challenges they face. That said, picking tomorrow’s corporate winners and losers via purchasing individual shares will not be easy. In this regard, investors should note an often little-appreciated benefit of index-based investing such as through exchange traded funds – survivorship bias. The indexing process automatically cuts exposure to poorly-performing companies over time, while re-weighting to new and more strongly-performing competitors – something you don’t get when buying individual stocks.

The structural changes will also give rise to major macro themes relating to technology, climate change, the emerging Asian middle-class, demographics, an ageing population, and energy and natural resource usage. Exchange traded funds can not only target the overall macro themes through diversified portfolios, but also specific sectors within an index. It is a faster-changing, more complex and harder to anticipate investment world. There are many reasons for optimism about the future of Australian companies but some of the star performers of today will struggle to adapt to the inevitable changes.

David Bassanese is the Chief Economist at BetaShares Capital, a leading manager of exchange traded funds. This article is for general information purposes and does not constitute personal financial advice.