At the beginning of 2021, when Inflation Scare 1.0 hit market sentiment, we focussed more on technological innovation, automation, the materially lower level of unionised labour and the economy’s reduced reliance on oil as continuing to drive the inflation declines that were evident prior to COVID-19.

Now the market is in a FUD, or Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt. FUD relating to inflation is the concern du jour, but I believe investors have little to worry about.

Inflation orbits a number of factors

First is the possibility that central banks are not only behind the curve, but asleep at the wheel. US inflation reached 6.2% year-on-year in October 2021, much higher than the market anticipated and even higher that the US Federal Reserve’s own forecasts of 2.1% in March and its more recent 4.2% forecast, in September. The high absolute level of inflation and its rate of acceleration have triggered sincere fears of an imminent and unsettling rise in interest rates.

Second, and despite apparent surging inflation, central banks continue their various forms of quantitative easing (QE). Some commentators suggest this activity is entirely inappropriate and will lead to hyperinflation. Keeping in mind such predictions serve to sell newspaper subscriptions more readily than they serve investors, hyperinflation is rapid, excessive, and out-of-control price increases of more than 50% per month. Not likely.

And it’s worth considering Japan’s QE program, which in proportion to its economy, is many times larger than the US package. Yet, despite its very aggressive programme, Japan continues to skirt with deflation not inflation.

Finally, many investors point to the fall in employment participation rates (referred to the Great Resignation in the US), and a surge in wages in some pockets of the economy, as a sure sign inflation will continue to accelerate and force central banks to inevitably raise rates.

Investors are right to be concerned about the consequences of higher rates. Large large, accumulated levels of global debt along with continued money printing - even as inflation surges - have even reputable investors fearing Armageddon.

It is important to distinguish fears from realities, but it is equally important to accept that either can trigger a market rout.

Use a longer-term lens

A longer-term lens better serves investors because it’s arguably easier to predict. Ask me whether ARB, Reece, Macquarie Telecom or CSL will be more valuable in a decade’s time and the answer is an unequivocal yes.

However, ask me whether their share prices will be higher next month or next year and I couldn’t say. It’s a far riskier proposition to predict the short term, even for the highest quality companies.

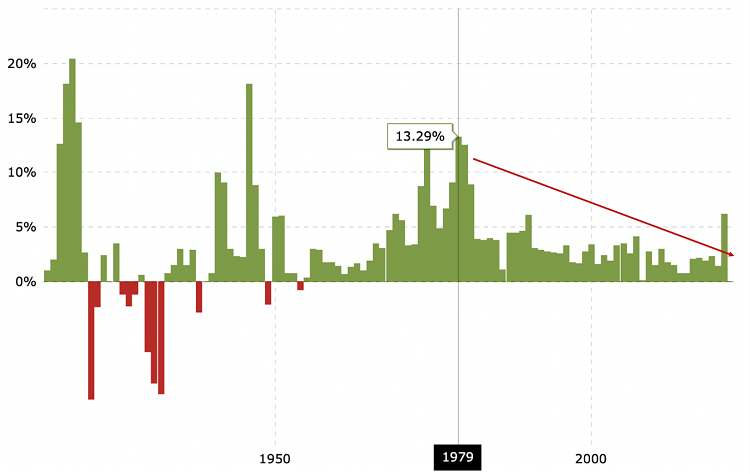

With that in mind, we believe low inflation is structural. Take a look at inflation in the US since the 1980s and one can see clear evidence of a shift lower for rates of inflation.

US historical inflation to 2021

Source: www.macrotrends.net

Expect structural decline of inflation to continue

Since 1979, when the US record year-over-year headline inflation of 13.3%, inflation has been in structural decline. This can be attributed to a number of factors that are unlikely to change.

First, the level of unionised labour is significantly lower than it was even 30 years ago. Large, coordinated and regular claims for wage increases are a thing of the past. The oft-reported thuggish and militant behavior of some unions has done them no favours in terms of their prospects for attracting a new generation of members. Their influence and therefore the prospects for rising wage pressure from this source remains in decline.

Second, and perhaps more important, investment in technology has accelerated. And technology itself is deflationary. Automation, AI, big data, digitization, information technology ... all are deflationary. Their advance is exponential, and they democratise access, which encourages competition. Technology lowers the cost of manufacturing, delivery and servicing, raising margins without the need to raise prices.

And one particular form of technology - automation - is directly responsible for displacing labour, keeping a lid on wages growth.

These are the structural forces promoting disinflation, and they have not disappeared. It remains valid to call inflation fears 'transitory'.

There are short-term factors

In the short term, we acknowledge the impact of a lack of immigration on wages in pockets of the economy. Competition amongst employers has seen wages rise in retail, digital, resources and construction. A reopening of the borders however will reverse these pressures and Australia and the US should revert to the trends in place prior to the pandemic.

History is replete with bouts of inflation coincident with an economic recovery from recession. While the cause of each recession differs, the response is usually the same – monetary and fiscal stimulation to support the economy. As the rate of economic growth eases and normalises, so too will inflation pressures.

Perhaps more obviously, the ‘base effect’ will work in reverse. Current high rates of inflation exist simply because we are comparing prices today to those recorded during the depths of the pandemic lockdowns last year.

This time next year however, a lower rate of price acceleration will be compared to the new higher base recorded this year. The result should be disinflation. At that time, we believe the market will take a sigh of relief, FUD could morph into FOMO (fear of missing out) and investors could return to the business of investing in high-quality businesses, especially those with structural tailwinds for growth.

Roger Montgomery is Chairman and Chief Investment Officer at Montgomery Investment Management. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.