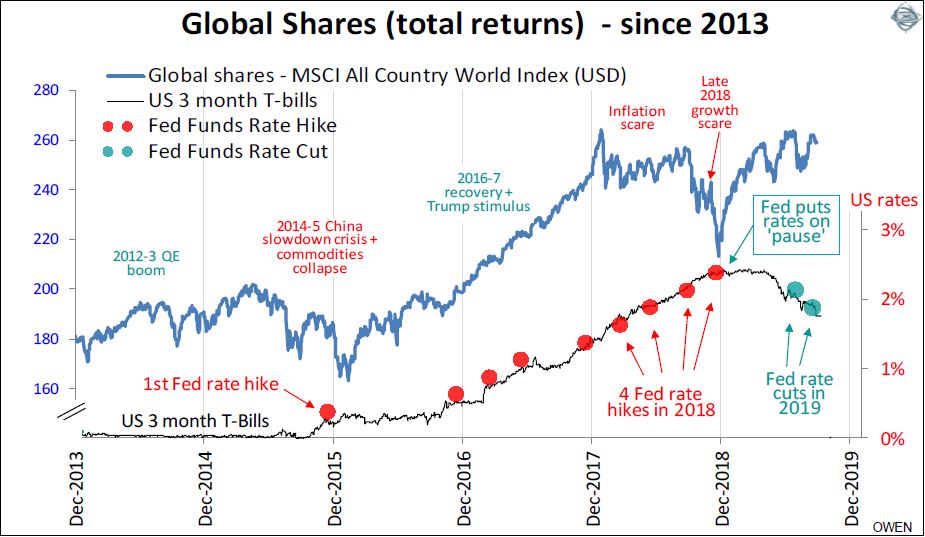

Calendar year 2019 has been a tremendous year for returns from investment assets of just about every flavour except cash. The single most important driver of financial markets in Australia and around the world has been US interest rate policy. Share markets sold off sharply in late 2018 and the main cause was the US Fed’s four interest rate hikes during the year, as shown below. Their stated intention was to continue raising rates several more times despite gathering signs of economic slowdown and fears of negative impacts from Trump’s escalating trade wars.

Then from the start of January this year, the Fed suddenly did a backflip and put further rate hikes on ‘pause’. Short-term rates started to drift down in anticipation of Fed cuts, and shares suddenly switched from the sharp sell-off to a strong rebound in 2019. The chart shows global share prices over the past five years through the US rate hikes (red dots) and now the rate-cut rebound (green dots).

The Fed is driving markets

Under intense pressure from President Trump, the Fed started cutting rates on 31 July. When it cut rates again on 8 September, Fed chair Jay Powell noted: 'Trade policy tensions have waxed and waned and elevated uncertainty is weighing on US investment and exports' - without actually naming Trump. Ever since nominating Powell to the Fed role, Trump has attacked him for not cutting rates back to zero.

The Fed is also coming under pressure to re-start its ‘QE’ bond-buying programme. Trump's trillion dollar deficits need funding, and that means the government is scaling up the issue of new bonds. The sheer volume of new bonds, plus the fact that China is now selling US bonds, will put pressure on yields to rise, unless the Fed starts buying them again. Share prices surged during the last ‘QE’ boom in 2012-14, and the prospect of more QE is also supporting share prices this year.

In Europe, the central bank had ended its ‘QE’ last year but with European economies, inflation and jobs growth still stagnant, on 12 September the ECB resumed its rate cuts (further into negative territory) and announced a re-start of its ‘QE’ program of direct bond buying. It didn’t work last time so there is little reason to think it will work this time. But it certainly did artificially boost returns from bonds and shares.

In Australia, the Reserve Bank has also cut rates three times more this year (including 1 October), bringing the total to 15 rate cuts in the current cycle that started in November 2011. It is running out of room to move. The banks are not likely to pass on any more rate cuts to borrowers as they are already facing margin squeeze and declining profits. The RBA has even talked up the idea of Australian ‘QE’ bond purchases.

Several other countries have also cut rates as Trump’s trade wars continue to escalate and growth prospects dim. (There are exceptions to this global trend – Norway has hiked rates four times to try to rein in rampant debt-funded property speculation). With interest rates on deposits cut almost everywhere, investors have stampeded back into shares, commercial property, infrastructure and bonds this year – boosting returns on all asset classes – except cash.

Although investment returns have been boosted across the board this year, it is unsustainable of course because interest rates can’t continue to be cut into negative territory forever.

What lies ahead?

Investors should not become complacent just because shares are doing well again. The rebound in 2019 has been due mainly to artificial and non-sustainable sugar hits from central banks. Meanwhile, out in the real world, economic activities like spending, lending, capital investment, trade and hiring, are slowing across the board.

It is true that Australia has managed to produce a rare budget surplus (and an even rarer current account surplus) but these have been due to unsustainable windfall gains from export commodities prices rather than spending cuts. On the contrary, government spending in Australia has increased at several times the rate of population growth and inflation, and in recent years the government has been the largest driver of employment growth. Outside of the government sector, the rest of the economy has been very weak.

What lies ahead is probably lower interest rates in Australia and in the major global markets - US, Europe and Japan – at the short end and also at the long end. This will most likely be accompanied by increases in government spending in Australia and the US, although there is less scope in Europe and Japan. These sugar hits will probably support asset prices as they have done in past rounds of rate cuts and QE. Governments cannot continue to increase their spending ahead of the growth in tax revenues required pay the interest bills.

There are two types of scares that rattle investment markets - inflation scares and slowdown scares. We have seen many examples of both types of scare in the past and we will see many more in the future. The difference between the two types of scare is their impacts on shares and bonds. Both shares and bonds suffer in inflation scares (both sold off in the February and October 2018 inflation scares), but in slowdown scares share markets fall but bond prices rise, as they did in the December slowdown scare. Inflation scares are the more difficult for investors as they hit both shares and bonds (including bond proxies).

The good news is that inflation scares (where both shares and bonds are hit) are less likely to be on a global scale now. The only risk of serious (say 5%+) inflation is in the US and Australia and some other small markets like Canada. We are unlikely to see serious inflation in Europe or Japan for many years – or perhaps ever, under their current political regimes. The problem (or good news for bond investors) is that Europe and Japan are dying – literally – with aging and declining populations, declining tax-payer bases, but rising welfare bills. One solution is immigration but this is proving politically impossible. The likely future is decay and deflation, not inflation.

On the other hand slowdown scares are more likely but they are less of a threat to investors because bonds (especially government bonds) tend to do well in big slowdown scares like the GFC, 2001-02 tech wreck and 1990-01 contraction.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.