Our instincts are generally poor guides when it comes to investing. Millions of years of evolution have left us with brains that are hard-wired to put safety first whenever we can. When faced with hunger, disease, or the odd Saber-toothed tiger, it’s hard to fault safety first as the go-to organising principle.

When it comes to more cerebral tasks, such as investing, these old instincts can sometimes cause us more harm than good. One of the best-known examples of this is what behavioural economists refer to as ‘loss aversion’, a phenomenon that sees us instinctively worry more about losing money than making money.

For example, when presented with a theoretical investment proposition that offers an equal chance of either doubling your capital (a 100% gain), or seeing it halved (a 50% loss), many of us will decline to make the investment, fearful of the 50% prospective loss. Meanwhile steely professional investors would relish such an opportunity, with the prospective outcomes (if not odds) stacked heavily in your favour.

Today a new form of loss aversion is stalking the investing public. With the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) having lifted interest rates by 4.25% over the past 18 months, there is a growing narrative in the market that holding cash has now become an attractive investment option in its own right.

At face value, the argument has a certain seductive appeal. Given the capital strength of the big four Australian banks, placing your savings into one of these banks is certainly an exceedingly safe thing to do. Moreover, relative to recent history, interest rates today are very high. Savings accounts at the big four currently offer rates of between 4 and 5%, a vast improvement on the circa 1% they averaged over the five years prior to the RBA starting to lift interest rates. Indeed, outgoing RBA chairman, Philip Lowe, said at one of his last parliamentary committee meetings that he had received many letters of thanks for lifting interest rates, and in the process finally letting savers earn a good rate of return on their cash investments.

The silent tax

The flaw to this logic is the factor that has driven interest rates so much higher recently: inflation.

Inflation is often referred to as the ‘silent tax’. Silent because we don’t see it reaching into our back pockets the way we see governments do when they tax us directly. But just because we don’t see it, it doesn’t make it any less real. Inflation works in the background to reduce the real-world buying power of our savings.

Over the past three years, the average basket of goods and services we buy in Australia has increased by 16.4%. If you had left your savings in a bank account over that time, you would have earnt 4.1% in interest. In the real world then, you are 10.6% worse off, even though your bank account balance looks higher.

Given the RBA is tasked with protecting people’s purchasing power by maintaining inflation at low levels (admittedly not an easy thing to do), those writing to Philip Lowe had more reasonable grounds to be complaining about significantly reducing the real value of their savings, rather than thanking him for lifting interest rates.

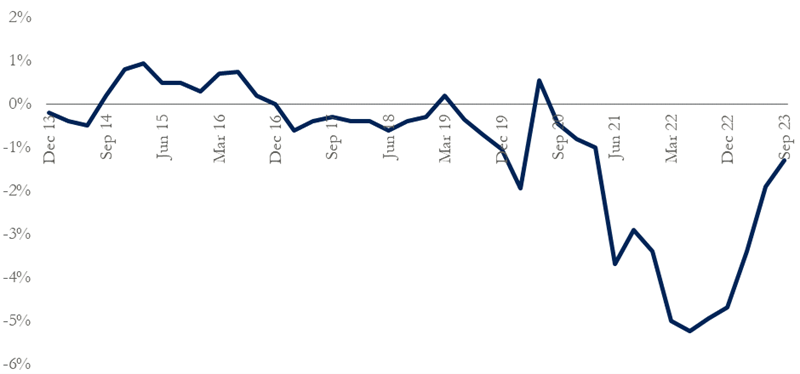

The chart below shows the prevailing RBA target interest rate less Australian inflation over the past ten years, to give an approximate real (or after inflation) measure of the returns that have come from leaving money in the bank.

Real Australian interest rates1

1RBA target overnight interest rate less Australian CPI. Source: Bloomberg LP

It has been a long time since savers could put money in the bank and earn a positive after-inflation return on their investment. The last few years, when inflation peaked at 7.8%, have been particularly grim. While inflation has begun to fall again, the last reading of 5.4% (based on quarterly CPI data which is considered more accurate than the monthly indicators) is still above any current interests that any major bank can offer. Instinctively, putting money in the bank always feels like a safe thing to do with your savings. Sadly today it is still guaranteeing you a negative real-world loss, given where rates of inflation are. Hardly an attractive investment option, in our view.

Other alternatives

The better news is that, in theory, higher base interest rates should mean higher prospective returns are available to investors across other asset classes. The most intuitive place to see this theory in action is in the debt world. With the RBA lifting rates as much as they have, the interest rate that is available to creditors when lending their money to companies has increased considerably. Two years ago the average yield on an investment grade bond in Australia was 2.1%, while it was 4.7% for sub-investment grade borrowers. Today those figures are 5.2% and 8.0% respectively.

Moving further out the risk curve, the same principle ought to apply to higher-risk assets, like shares. As base interest rates go up, the discount rates used to value these assets moves higher. In theory, that should mean prices fall in tandem with rising rates, but that after this adjustment, future expected returns should be higher than they were historically, reflecting the new higher base rate in the economy. Unfortunately, theory and practice do not always come together perfectly (witness Australian property prices, where predictions that higher rates would lead to a correction have failed to eventuate).

Nevertheless, investors today should be armed with the basic principle that higher RBA base rates should mean higher prospective returns from their investment portfolios (or their fund managers) and be demanding as such. It will only be with these higher returns that any of us can look forward to a real (after inflation) return on our savings.

Miles Staude of Staude Capital Limited in London is the Portfolio Manager at the Global Value Fund (ASX:GVF). This article is the opinion of the writer and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.