In September 2022, the UK government released a budget update and economic plan. By mid-October 2022, both the Prime Minister and the Chancellor of the Exchequer had resigned due to the significant increase in borrowing required to fund the new fiscal policies, which led to a substantial sell-off of UK government bonds and skyrocketing yields.

More recently, following the outcome of the US Presidential election, there has been close monitoring of US fiscal policy and its implications for bond issuance in 2025 and beyond. However, one market that hasn’t seen as much focus is Australia. Could this be about to change?

Elevated Government spending

The RBA Governor, Michelle Bullock, mentioned the higher-than-expected growth in government spending in Australia in a recent press conference. In fact, the RBA has highlighted the high level of government spending several times over the past few months.

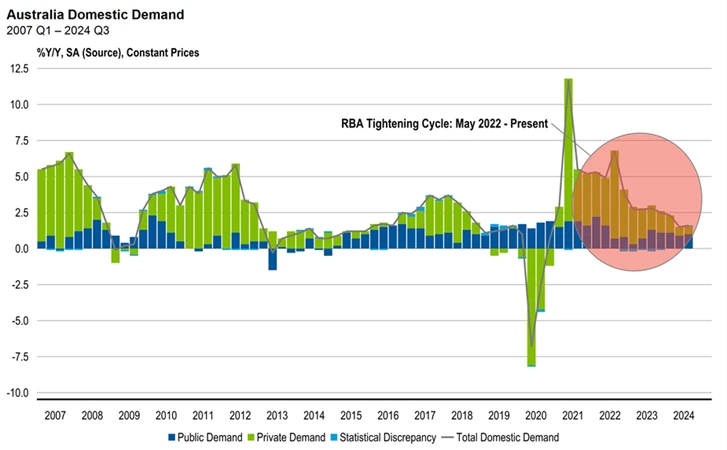

Exhibit 1 below shows Australian domestic demand by sector. The private sector is reducing its spending in response to higher interest rates, which is helping to rebalance the economy. The economy was growing at an above-trend rate for several quarters, and this triggered the most severe bout of inflation seen in decades. But while the private sector is adjusting, the combined government sector continues to spend at elevated levels.

Exhibit 1: Australian Domestic Demand by Sector, 2007 Q1 – 2024 Q2

Source: Franklin Templeton, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Macrobond.

This spending is broad-based. At the national level, the spending shows in government-related employment growth, particularly in the health care industry. However, high commodity prices over the past few years have boosted revenue and led to a national budget surplus. If only this were the whole picture…

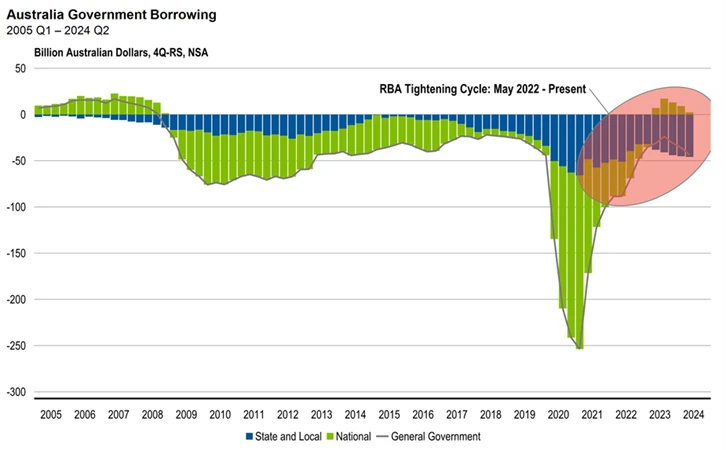

In Australia, a significant portion of government spending occurs at the state and territory level. And this is where the numbers aren't so rosy. Some states, such as Western Australia, are reporting strong budget surpluses due to high commodity prices. Conversely, other states are reporting large deficits as soft property markets limit revenue growth and large investment pipelines boost expenditure growth. The fact that many of these projects are behind schedule and over budget exacerbates the situation.

When we examine the effective level of government borrowing, it becomes clear that the states and territories are living beyond their means at a time when the RBA is advocating for more frugality.

Exhibit 2: Australian Government Borrowing, 2005 Q1 – 2024 Q2

Source: Franklin Templeton, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Macrobond.

Bond issuance is key

But what does this have to do with bond vigilantes?

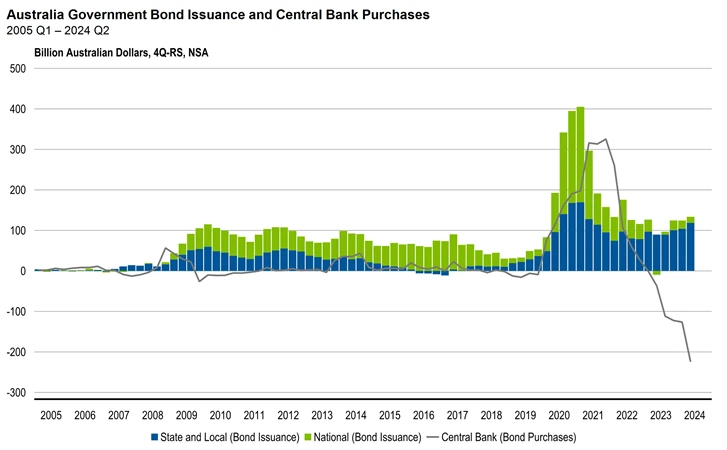

It is all about bond issuance. In the early stages of the pandemic, both the national and state/territory governments increased bond issuance to finance assistance packages. This was paired with the RBA purchasing government bonds as part of its response to the pandemic. Remember 'Team Australia'!

Since then, national government bond issuance has normalised. In fact, it is running below the pre-pandemic level thanks to the tailwinds noted above. In contrast, state and territory governments are issuing a significant amount of debt at a time when the RBA is transitioning from being a net buyer of bonds to a net seller. This is when bond vigilantes pay close attention.

Exhibit 3: Australian Government Bond Issuance and Central Bank Purchases, 2005 Q1 – 2024 Q2

Source: Franklin Templeton, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Macrobond. Note: State and Local includes issuance by Central Borrowing Authorities.

Whilst we do not manage portfolios against a UK government bond benchmark, it is safe to assume those benchmarks performed poorly in late 2022 amidst the bond market turmoil.

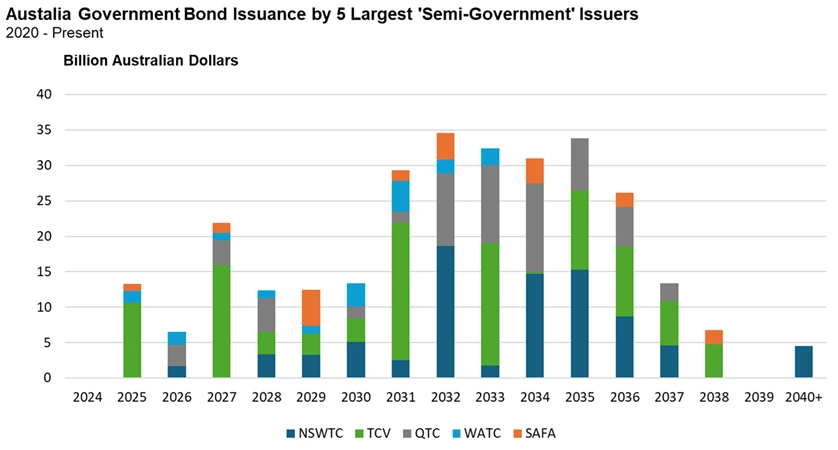

When considering the outlook for Australian government bond benchmarks, specifically the AusBond Composite Index, we are particularly concerned about the level of bond issuance from the states and territories. These issuers, collectively termed the 'Semi-Government' sector, have shown a preference for issuing mid- to longer-dated bonds, i.e., 5- to 15-year maturities, as illustrated in Exhibit 4 below.

This trend does not bode well for the performance of the AusBond Composite Index and arguably goes some way to explaining its relatively poor performance, despite many central banks commencing rate-cutting cycles.

Exhibit 4: Australian Government Bond Issuance by five Largest ‘Semi-Government’ Issuers, 2020 – Present

Source: Franklin Templeton, Bloomberg.

Global bond markets have their fair share of headwinds at present.

The US government is issuing record amounts of debt, with neither major political party showing interest in balancing the budget. Japan might finally tighten its monetary policy, reversing a strategy that flooded the local market with liquidity and compelled Japanese investors to be net buyers of global government bonds.

Additionally, the demand for capital from the private sector is likely to increase to finance clean energy investments. All these factors suggest that interest rates will remain higher than pre-pandemic levels.

Against this backdrop, Australia's state and territory issuers need to find buyers for their bonds. The national government is also just an iron ore price drop away from needing to issue a much larger amount of bonds. Fixed income can still serve as a defensive asset class, but perhaps not in benchmark form. Beware the bond vigilantes.

Joshua Rout, CFA is a Portfolio Manager and Research Analyst at Franklin Templeton Fixed Income. Franklin Templeton is a sponsor of Firstlinks. This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice.

For more articles and papers from Franklin Templeton and specialist investment managers, please click here.