The relationship between bonds and equities is a feature of all balanced portfolios, especially how the price of one moves in relation to the other. Correlation is a measure of the strength of the co-movement, with a positive correlation indicating prices usually move in the same direction.

As this relationship drives the performance of superannuation for many Australians, it’s useful to know how the correlation between bonds and equities has varied over longer time periods. This article also looks at some of the key drivers of the correlation structure, and how different levels of correlation impact a portfolio’s performance.

Correlation between bonds and equities over longer time periods

Questioning the persistence of the negative correlation between equity and investment grade fixed income price returns (that is, when equities rise, bond prices fall and rates rise, or when equities fall, bond prices rise and rates fall) has become timely because of the intersection of a few topics.

In particular, co-movement of the equity and sovereign bond markets during the March 2020 market sell-off reignited the concern about the hedging potential offered by fixed income assets. This led to a reinvestigation of the sovereign bond-equity correlation relationship, a relationship that has been negative over the past two decades. Many argue that much of this negative correlation can be attributed to the lowering and persistently low levels of inflation over this same period.

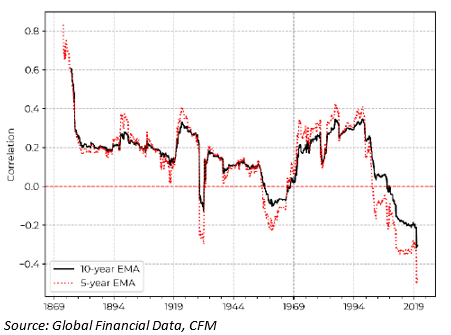

While stock and government bond prices have been moving in opposite directions since the beginning of the new millennium, the correlation prior to around 1997 in the US, as seen below, was broadly positive for more than a century. Using data going back to the mid-19th century, the correlation between equities and bonds has been mostly positive, making the recent and consistent stretch of negative correlation the anomaly, rather than the rule. (EMA=Exponential Moving Average).

Long-term evidence of positive correlation between bonds and equities

How do different levels of correlation impact returns?

Investors use the Sharpe ratio as a measure of risk-adjusted returns, or how much excess return you receive for taking more risk. You would expect a higher return from an equity portfolio than a bond portfolio over time because equities are more volatile (and, by this measure, riskier).

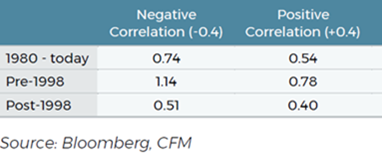

The table below shows the Sharpe ratios of a 60/40 portfolio in three different time periods: 1980-today, 1980-1998 and 1998-today.

The latter two periods are characterised by the flip in correlation that occurred in 1997. In the first column of the table, we assume an arbitrary -0.4 correlation between equities and bonds and recalculate the Sharpe ratios. We repeat for the second column with an arbitrary +0.4 correlation.

What is striking is the increase in pre-1998 Sharpe ratio from 0.78 to 1.14 by flipping the correlation, and from 0.40 to 0.51 following the same flip in sign for the period post-1998. So the risk-adjusted returns of a 60/40 portfolio are very sensitive to the level of correlation between equities and bonds!

How have other ‘safe-haven’ assets performed in difficult markets?

Asset managers have become accustomed to being able to rush into the safest and most liquid of assets, typically US treasuries, as a hedge when equity markets sell-off.

The ‘protective’ property of so-called ‘safe-haven’ assets such as US treasuries (and other low risk sovereign debt, gold, and especially the currencies of the US, Japan, and Switzerland) has been called upon to hedge equity exposure in periods of high (and often continued) market stress and significant drawdowns.

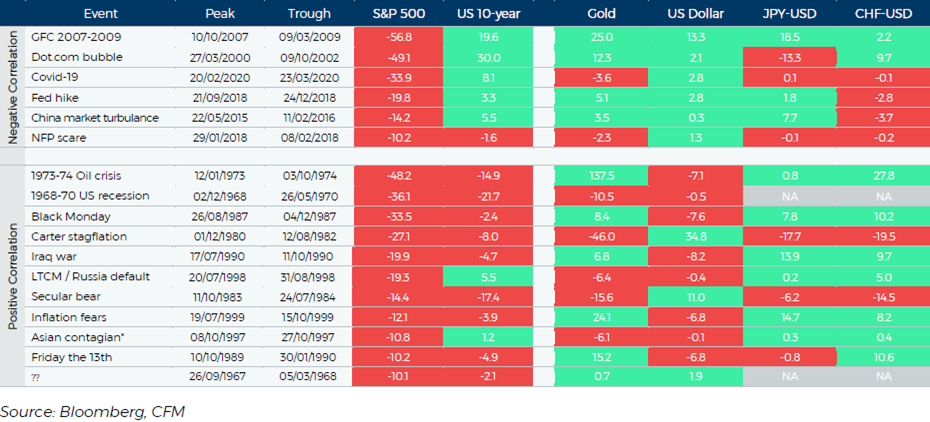

However, this market feature, looking back over the past 60 years, has only recently been available to all investors. In the table below we show all equity drawdowns (market falls) greater than 10% since the 1960s. We tabulate the total return of the S&P 500 from peak to trough, along with the comparative total return of US treasuries along with other major safe-haven assets. There is a distinctive pattern, corresponding with the correlation structure of equities and bonds as discussed above.

Before the end of the 90s, bonds typically moved in lockstep with equities, offering no protection to investors during these, the most severe drawdowns. Even in the couple of cases it did, the returns were marginal. However, after the end of the 90s, the pattern changed markedly, when, in most cases, bonds acted as an effective hedge against the equity sell-off.

Our conclusions

Given these observations, both the return and hedging potential of bonds are reduced when interest rates are low and correlations are positive.

If bonds become a less effective hedge for portfolios, investors will be left with few choices other than an expensive portfolio of options. We think they would be better advised to look for alternatives to bonds for diversification in the current environment.

Craig Stanford is a Director of Capital Fund Management. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. Any description or information involving investment process or allocations is provided for illustration purposes only. There can be no assurance that these statements are or will prove to be accurate or complete in any way. All figures are unaudited. This article does not constitute an offer or solicitation to subscribe for any security or interest.