Despite the fact that gold has increased in price from below AUD450 an ounce to over AUD1700 an ounce since the turn of the century, investors in developed markets remain reticent to invest in gold today.

In the late 1990’s, gold was languishing below AUD500 an ounce, having suffered a near double decade bear market. No yield, ongoing storage costs, and significant opportunity cost does not a happy investor make.

It wasn’t just investors, with central banks net sellers of the metal from the late 1980s until the onset of the GFC, divesting close to 6,000 tonnes over this 20-year period. One of those central banks was the RBA, which in 1997, sold off roughly two-thirds of Australia’s national gold reserves, netting some AUD2.4 billion in the process.

What was the RBA thinking?

The rationale for the RBA gold sale was in a detailed memorandum prepared in December 1996. The memo noted that gold represented some 20% of foreign exchange reserve assets, and that there was considerable cost of holding this reserve, especially in terms of income foregone. When looking at the outlook, the memo noted that “it would be optimistic to expect sizeable increases in the price of gold in the near term”.

It also included the table below, which contains the returns on physical gold vs. US Treasuries.

Compound annual returns (percentage)

This analysis was partly used as justification for the gold sale, with the memo stating that:

“The value of $100 invested in US Treasuries in 1900 would now be about $3,700 (assuming all coupons were reinvested), which is about twice the value of a similar investment in gold.”

Whilst the data is accurate, the insight drawn was questionable at best, for the memo itself noted the gold price was fixed until 1971. Had the 70-year period where gold prices were fixed been removed, then the return comparison of gold versus US Treasuries would show that the yellow metal’s performance was double that of Treasuries.

Impact of the physical gold sale

Those 167 tonnes would be worth close to AUD9.4 billion today. The decision to sell at an almost double-decade low has cost some AUD7 billion in capital gains foregone. In fairness to the RBA, we must acknowledge the growth of the proceeds they received for the gold sale. Given the duration profile of their assets, and the countries they invested in, the return on 2-year US Treasuries between March 1997 and March 2018 would give an annualised return of 2.54%. The proceeds of the gold sale would be worth some AUD4.1 billion by now, meaning the decision by the RBA to sell back in 1997 has likely cost the nation back closer to AUD5.3 billion.

Make Australia gold again

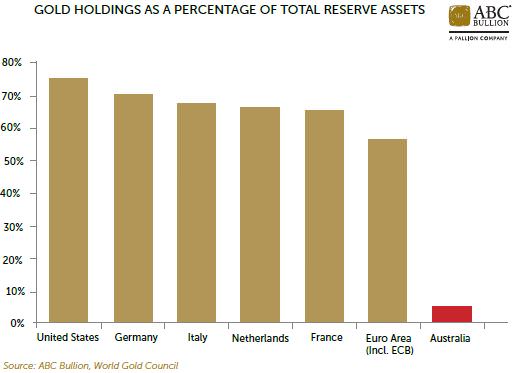

RBA gold holdings currently make up less than 5% of our foreign reserve assets, a number that is alarmingly low compared to the holdings of other developed market nations, as the chart shows.

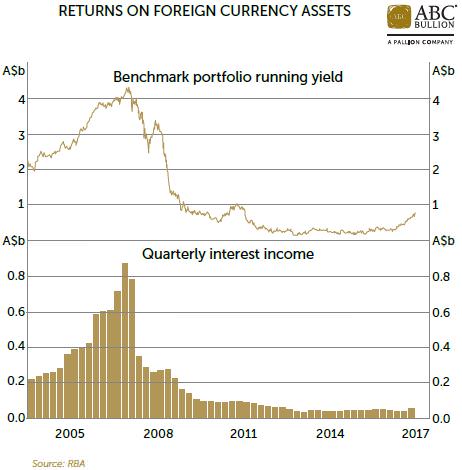

There is now a lack of income being generated on our portfolio of foreign exchange assets. The latest RBA Annual Report includes the following chart, which highlights the fact we earn less than 1% on our assets.

Given the RBA actually earns roughly 0.20% on its gold loans (contrary to popular opinion, one can earn a yield on gold), the opportunity cost of holding gold is now far less.

A central bank (or any investor) might look to trim their gold holdings if they could earn over 4% in ‘real’ terms investing in low-risk, low-volatility financial assets, but we are not operating in that environment today, and likely won’t be for years to come.

The deterioration in public sector balance sheets across the developed world will almost certainly result in higher inflation in the coming years, adding weight to the argument that the RBA would benefit by topping up our physical gold reserves.

Central bank gold buying is a global trend

Since the GFC, central banks have turned net buyers of physical gold. Collectively, they’ve purchased the better part of 3,000 tonnes of gold in the past eight years with total official gold reserves now back to where they were in 1999.

The buying has been spearheaded by emerging market nations, including China, India, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Turkey, many of which are likely to be accumulating for some time too, as on average, they still have less than 8% of their reserves in gold, far below that of the United States and many European nations.

Since the GFC, Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany, have all either moved, or are taking steps to move some of their gold holdings back within their own borders. Central banks are in no doubt as to the importance of holding gold, and the RBA should take note.

Time to move back to 1997

Given the paucity of yield on offer in sovereign bonds, the prospect of higher inflation and gold’s unique attributes as a monetary asset, now is the time for the RBA to begin increasing our gold reserves. A 15-20% weighting would be appropriate, in line with our holdings prior to the 1997 gold sale, and roughly equivalent to the proportion of foreign reserve assets that gold constituted when the ECB was formed back in the late 1990s.

A significant portion of these reserves should be held within Australia. Australia is a politically stable, AAA-rated sovereign. There seems little point in mining and refining physical gold in Australia, only to have all of our national gold reserves held offshore.

Storing national gold reserves locally would also send a positive message to Asia, where gold is seen as money by both citizens and central banks alike. Provided it was leveraged the right way by the private sector, it could grow our banking and financial services links with the region.

Rebuilding our national physical gold reserves will better balance out the RBA’s reserve assets for what may be some rough years ahead.

Jordan Eliseo is the Chief Economist for ABC Bullion, Australia’s largest private bullion dealer and precious metal depository. This article is in the nature of general information only and not intended as investment advice.