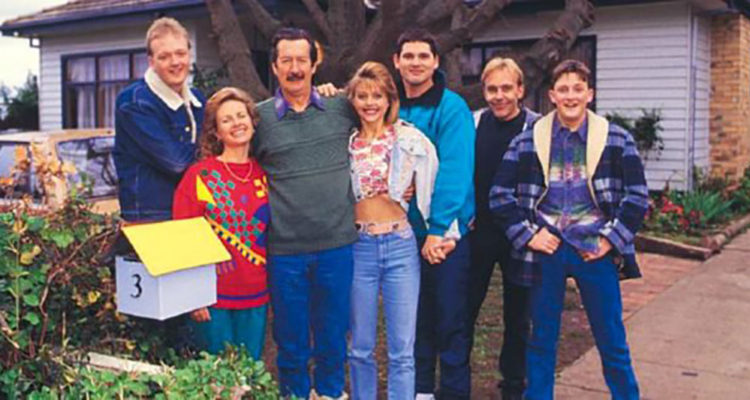

In 1997, the low-budget cult hit film, ‘The Castle’, which depicted the quintessential Aussie family and the fight for their home, was released to critical acclaim. The famous line, “A man’s home is his castle”, captured then, as now, the Australian dream of owning a home, traditionally one’s largest and most important asset. Little did the Kerrigans, introduced to us a mere five years after compulsory superannuation, realise that we’d accumulate trillions of dollars in superannuation wealth, increasingly concentrated in mega funds that have now become some of the largest allocators of capital in the world.

In the last decade, these mega funds have increasingly been allocating low and middle-income Australia’s hard-earned dollars in sophisticated and opaque unlisted assets. Gone are the days of just owning a holiday rental in Bonnie Doon. The Kerrigans are now private equity investors.

The problem is these assets don't trade on an open market and are valued infrequently. Big super, or the mega funds, sell this as a feature, smoothing the ups and downs of the investment cycle. However, as these funds offer thousands of co-mingled members daily liquidity to contribute or withdraw funds, there is a funding mismatch. And are these valuations fictitious or real?

How private equity returns are calculated

Private Equity 101 would suggest we ask a private equity manager what their historical rate of return - typically measured as Internal Rate of Return (IRR) - is across all their deals. Breaking up this track record across funds or ‘vintages’ also helps to consider a manager’s performance across the investment cycle. Whilst gross IRR reports total return, net IRR shows the return net of all fees, essential for assessing how much of the pie the manager is eating before they feed you. Realised IRR shows the return to investors from investments that have been exited. If Net IRR is notably higher than Realised IRR, then unrealised investments in the strategy may be getting carried at very high values.

The Total Value to Paid In ratio (TVPI) measures the sum of distributions and carrying value on investments made as a multiple of all funds paid into that vehicle. For example, a TVPI of 2.0x would indicate that at today’s carrying value, an investor has doubled the money they have contributed – paper wealth. The Distributions to Paid In ratio (DPI) strips out carrying value and merely shows how much has been paid back to date – money in the bank. The goal is to convert carrying value embedded in TVPI into DPI as a vintage matures and underlying assets are successfully exited. If a manager has old vintages where TVPI is still much larger than DPI, questions need to be asked.

Currently the amount of TVPI over DPI is at record levels at an industry level. As carrying values have become inflated over the last decade, some experts estimate that it will take as much as $600 billion of impairments in Venture Capital alone to get TVPI back down to historical norms. Private Equity is an even bigger beast.

Since 1994, 1,276 private equity funds over $1 billion have been raised around the world. Only 22 have managed to return more than 2.3x, a return considered consummate to compensate for the risk and illiquidity of these investments. The law of large numbers dictates the larger a private equity fund is, the harder to realise returns. Larger ‘winners’ are required to pay back the invested capital, something data shows is hard to do at scale. Yet the big super funds, due to their size, often preference these larger deals.

Private market valuations haven't caught up to public markets

It’s hard to know if these dynamics are at play within the super funds, yet as the liquidity tide goes out and public market valuations have been crushed, requisite valuation moves are yet to occur in private markets. Much of the capital globally has been allocated in recent vintages at a time when carrying values and TVPI are far above historical norms. If they invest like private equity investors, Big Super should be required to report like private equity investors. What is the level of unrealised returns they are reporting to members relative to the historical norms they have traditionally been able to realise?

As the illiquidity of these funds' increases, so too does their liquidity risk. Worryingly, APRA has said some funds lack formal liquidity and stress-testing processes whilst others fail to incorporate results into the investment decision making process. All these funds offer daily liquidity and pricing to members who are free to withdraw pensions, contribute funds or switch investment options at the click of a button. Yet many of the underlying assets are valued quarterly at best and are completely illiquid.

Reform is needed

Standardised liquidity and stress testing should be introduced, and the findings made public, along with the methodology and assumptions used, just as it is for banks. This way, Australians can assess the funding risks inherent in their super.

Innovations are on the way to provide more liquidity for unlisted assets. Platforms where investors can allocate to private assets, but also realise them sooner by listing them in a secondary market, are now available. Listed Investment Trusts (LITs) and Listed Investment Companies (LICs) are vehicles listed on public exchanges that can hold unlisted assets and provide daily liquidity at prevailing market pricing. Given disclosure requirements in public markets, reporting is essential and far superior to that provided by the mega funds.

Previously exploited by public market equity managers as asset gathering exercises, the image of LITs and LICs has been tarnished by conflicted commissions, poor performance and thin liquidity. Rejuvenation efforts are underway to build and scale these listed vehicles into credible offerings of unlisted assets for the masses.

Further out on the horizon, massive investment in financial technology and innovation is taking place. The best software engineers from the best schools are joining the crypto and blockchain arms race to create the most effective ‘Dex’s’ (Decentralised Exchanges) that contain ‘AMMs’ (Automated Market Makers), which pool liquidity from users and price assets using algorithms. The aim is to create deep liquidity for all assets at low transaction fees 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, where nearly any asset or ownership right can be tokenised with key terms coded into a smart contract.

Whilst many attempts will fail, the history of finance and money has taught us that innovation always outpaces regulators and governments. It's innovation that is required to reduce these frictions. Such change will take decades, but the irony is some of the biggest problems associated with unlisted assets may come from the private markets themselves.

In the interim, Big Super will argue that increased disclosures and scrutiny will divulge commercially sensitive information that is contrary to their members’ interests. The reality is the information can be presented in a way that respects these concerns. Whilst a reasonable allocation to unlisted assets can improve portfolio outcomes, transparency is key, so risks can be properly scrutinised.

Kieran Rooney is a Senior Consultant at Evergreen Consultants. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.