Despite the very long-term nature of the Australian superannuation system, investors can move between options and super funds on a daily basis. This liquidity mechanism means the liquidity profile of a fund cannot be ignored. But looking at the level of illiquid assets as a proportion of total assets is only part of the story. Understanding the future cash flow profile and member demographics of the fund also gives an indication of the sustainability of the level of illiquid assets. While liquidity stress-testing is required to be conducted by funds under SPG530 – Investment Governance, the level of public disclosure on this issue is limited.

We attempt to piece together some key metrics of a handful of large funds to see how they stack up.

Which funds?

The five funds selected for the purposes of the analysis are: Australian Retirement Trust, AustralianSuper, Aware Super, Cbus, and UniSuper. Of the roughly $2.25 trillion of total fund assets reported to APRA as of 30 June 2022, these five funds represented almost 40% of this pool.

Unlisted as a proxy for illiquid?

Measuring illiquidity is challenging. The number of days an asset can take to trade is often a guess, particularly when it comes to individual assets not traded on exchanges. Even when the assets are traded on an exchange, asset managers try to predict liquidity by understanding average daily trading volumes, which can fluctuate wildly depending on the security and market conditions. The available liquidity of unlisted assets is even more of a challenge to predict.

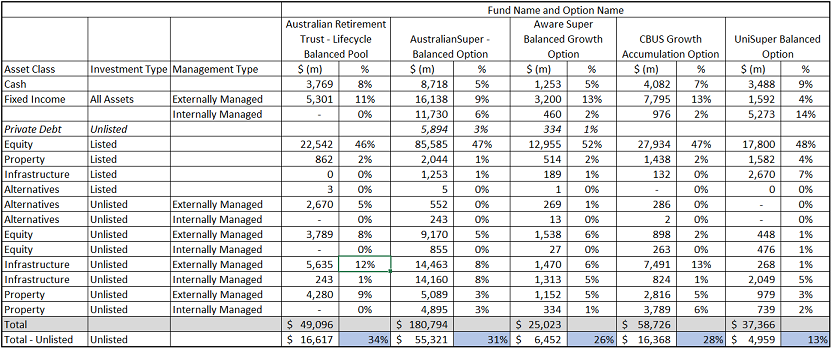

As imperfect as it may be, this analysis uses the Portfolio Holdings Disclosures, which specifies a super fund’s allocation to 'unlisted' assets for a particular option. The funds’ larger options, typically in the balanced and growth categories, have been selected for the analysis.

‘Unlisted’ does not necessarily equal ‘illiquid’; ‘unlisted’ is defined as a security not traded through an exchange under the regulations. There are plenty of ‘unlisted’ funds that hold listed equities that are traded daily through an exchange, and you could receive your money back from the ‘unlisted fund’ in a matter of days - which is a highly liquid proposition. There will also be ‘unlisted’ funds that hold illiquid assets.

‘Illiquidity’ is a spectrum. A security or unlisted fund could take a few days, a few weeks, months or even years to return money back to the investor. Unfortunately, the liquidity ladders of super funds are not made available. That is, the assumed proportion of a fund that could be liquidated in one week, four weeks, three months, one year, and so on is not disclosed. So, in the absence of disclosure, ‘unlisted’ will crudely be used as a proxy for ‘illiquid’.

Unlisted allocations of the big funds

There are varying levels of unlisted assets held across these large super funds’ options. Australian Retirement Trust’s Lifecycle Balanced Pool holds the highest level of unlisted assets at 34%, UniSuper’s Balanced Option holds the lowest level at 13% and AustralianSuper’s Balanced Option sits at around 31%.

The level of illiquid allocations as a percentage of the total portfolio will move around, particularly in periods of volatile listed markets. When listed markets are declining in value and illiquid markets are either remaining static (due to mark to market pricing stability) or declining to a lesser degree, the illiquid allocation will naturally become a higher proportion of the portfolio through this period.

During 2022, we witnessed a strong selloff in both listed equities and bonds, and a weak Australian dollar. This selloff did not impact the asset prices of private markets to the same degree and, as a result, it's likely that some of these unlisted allocations are slightly higher than fund targets.

Exhibit 1 Super fund options by asset class, investment type, and management type

Source: Portfolio holdings data disclosed on fund websites as of Dec. 31, 2022. [Click to enlarge]

Illiquidity through another lens

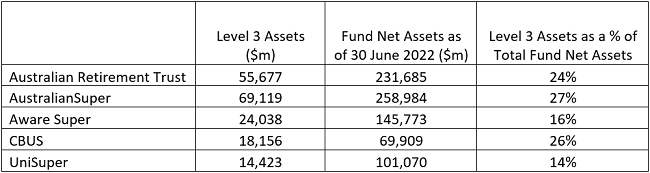

Another way of understanding the nature of assets held by superannuation funds is to dig through the annual financial statements where the accounting standards require a breakdown of estimated fair values for different market types using a hierarchy. The hierarchy basically scales from Level 1 (mainly listed equities where there are readily available quoted market prices) through to Level 3 where there isn’t observable market data and therefore fair values are based on unobservable inputs. The more-illiquid assets such as infrastructure, private credit, property, and private equity are typically included in this third level.

Exhibit 2 Level 3 assets (fair value in an inactive or unquoted market) as a % of total fund net assets as of June 30, 2022

Source: Annual financial statements 2022.

Exhibits 1 and 2 are not perfectly comparable given one considers each fund's assets invested in Level 3 assets and the other considers a particular fund option's exposure to unlisted assets.

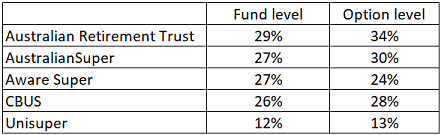

What do the funds say?

Of course, the other method of defining levels of liquidity is to just ask the superannuation funds, and their interpretations are displayed in Exhibit 3.

Exhibit 3 Fund- and option-level illiquid allocations at Dec. 31, 2022, as reported by the funds

Source: Fund responses.

Money coming in and money going out

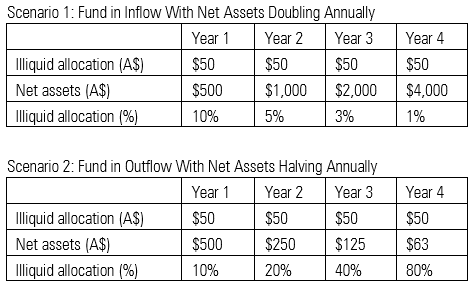

When it comes to liquidity, the money coming into or moving out of a fund is highly relevant. To illustrate the point using an extreme example, if a fund has net assets of $500, and in Scenario 1 the net assets double each year, the illiquid allocation diminishes quickly. Conversely, if a fund has net assets of $500, and in Scenario 2 the net assets halve each year, the illiquid allocation ramps up quickly.

Each year under APRA’s annual fund-level superannuation statistics, funds must disclose the level of flows broken down by member contributions (inflow), member benefit payments (outflow), rollovers (inflow/outflow), and flows as a result of merger activity.

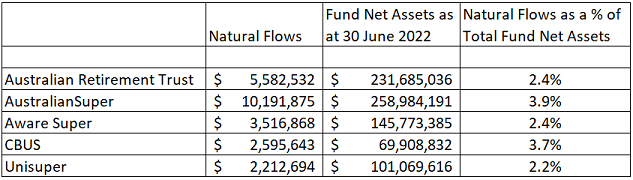

The Conexus Institute established a neat framework for thinking about the types of flows in their State of Super 2023 Booklet. For the purposes of considering the liquidity profile of a fund, Exhibit 4 considers 'total members' benefit flows in' (that is, superannuation employer and member contributions) and 'total benefit payments' (that is, lump-sum withdrawals and pension payments), termed ‘Natural flows’ in the Conexus Institute’s research.

Exhibit 4 ‘Natural flows’ as a percentage of total fund net assets as of June 30, 2022

Source: APRA annual fund-level superannuation statistics as of June 30, 2022.

Exhibit 4 shows that when it comes to natural flows, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of total fund net assets, AustralianSuper is winning the war. It’s worth highlighting that Cbus is also doing a good job of capturing flows as a percentage of its net asset base.

Member demographics and cash flows

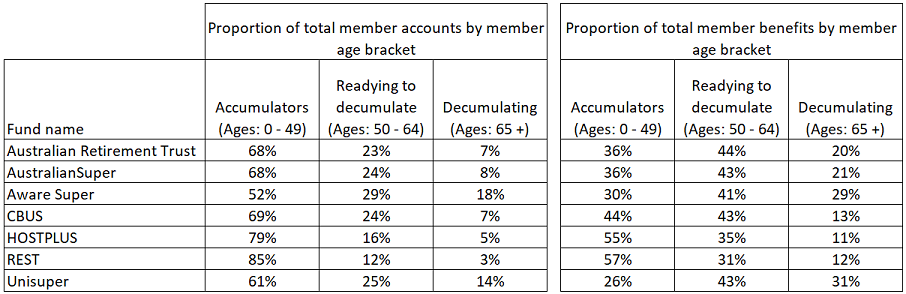

‘Natural flows’ will be impacted by the demographics of a member base. For example, an older member base will likely be drawing down their superannuation rather than contributing to it. Further, how the profile of a member base changes over time should also impact the liquidity profile of a fund. If a fund knows that a significant portion of its member base is nearing retirement and will either start drawing down its super balance or switch funds, liquidity levels should shift in response.

As shown in Exhibit 5, some funds have a significantly higher proportion of their member base who are decumulating. Hostplus and Rest superannuation funds have been included in Exhibit 5 to contrast the proportions for funds with a substantially younger member profile.

Exhibit 5 Proportion of total member accounts and member benefits by member age bracket at fund level

Source: APRA annual fund-level superannuation statistics as of June 30, 2022.

Theoretically, this logic should be applied at the option level, too. If a fund were to segment their member base, some options should hold higher proportions of illiquid and riskier assets (that is, options invested in by much younger, accumulating members), and other options invested in by older members may need a lower level of risk and more liquidity. Fund-level analysis is only part of the story, but this level of portfolio personalisation is still a way off for many funds.

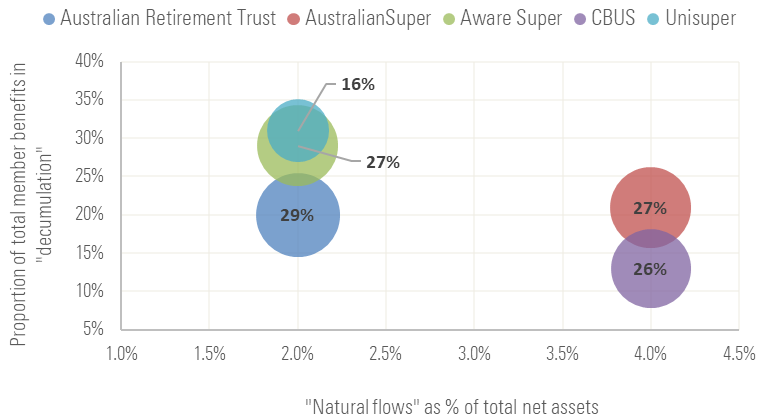

Exhibit 6 Comparison of proportion of illiquid assets* at fund level (as labelled in bubble) relative to natural flows as a percentage of total fund net assets and the proportion of total member benefits in decumulation.

Source: Morningstar. *Bubble size reflects proportion of illiquid assets at fund level as reported by the funds.

Given the higher proportion of decumulating members at UniSuper and the lower levels of ‘natural flows’ relative to these other funds, it makes sense that UniSuper have lower levels of illiquid assets under the measures considered. But there is no perfect answer to the right level of illiquid assets.

How illiquid is too illiquid?

Under the Corporations Act, guidance is provided for managed investment schemes. The provision states that “a scheme is liquid if liquid assets account for at least 80% of the value of the scheme property.”

The best we can hope for is that fund trustees are focused on their Liquidity Management Plans and how they stand up to different market conditions. Notably, the funds passed the test handed down in early 2020 - including the Early Release Scheme introduced, the aggressive selloff in listed markets, and the level of switching that occurred in response to volatile markets.

But it would be remiss to get too comfortable. A run on a fund (or a bank) can happen at any time, and Silicon Valley Bank is a timely reminder. Large member outflows, a risk-off environment where listed markets selloff aggressively, and the Australian dollar in free fall would see funds' allocations to illiquid assets likely increase as a proportion of total assets. Ongoing regulatory oversight of this issue is critical, and increased public disclosure on funds’ liquidity profiles would be welcome.

With its long-term framework, the retirement system supports the ability of superannuation funds to buy multigenerational (often illiquid) assets, which should deliver great returns for investors over time. However, we need to preserve the sustainability of such a system to ensure the illiquid component of these funds are prudently managed.

Measuring liquidity is complex with interrelated factors, but currently there isn’t cause for alarm across these five funds.

Annika Bradley is Morningstar Australasia's Director of Manager Research ratings. Firstlinks is owned by Morningstar. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. This article was originally published by Morningstar.

Access data and research on over 40,000 securities through Morningstar Investor, as well as a portfolio manager integrated with Australia’s leading portfolio tracking service, Sharesight. Sign up to a free trial below:

Try Morningstar Investor for free