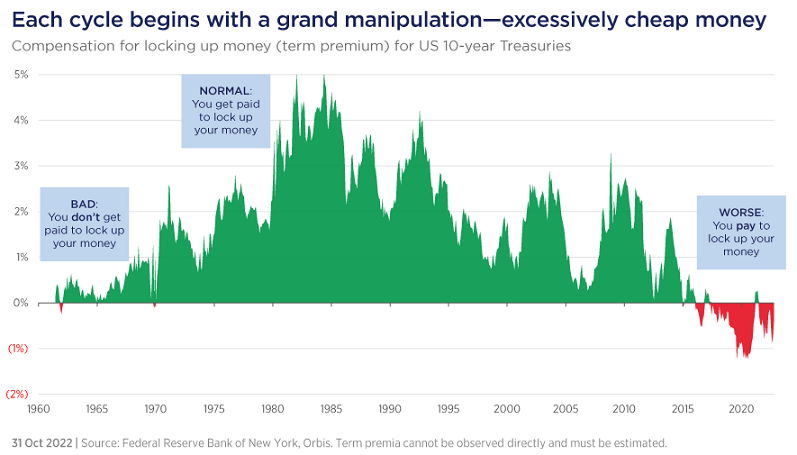

There is no logical reason this chart should ever go into negative territory. That it has is a clear indication that the market’s relationship with money has become distorted and has been for a long time.

What is a term premium?

This is the compensation you get for agreeing to lock up your money, for taking on 'time risk'. The longer you lock your money away, the more time there is for unexpected things to go wrong and the more of a ‘premium’ or added incentive you should be paid to make it worth your while.

In a normal economic environment, you should get paid more to hold a bond that matures in 10 years than you do to hold 10 one-year bonds, for example, because you’re taking on that extra risk.

Currently, as the chart shows, investors must pay for the privilege of locking up their money for 10 years in US government bonds.

This suggests that investors don’t think any premium is required; that essentially money today is no more valuable than money tomorrow, or next year or in the next decade and as a result they aren’t demanding extra rewards to offset that long-term uncertainty.

This extremely loose money, or negative term premium, environment has tended to favour growth stocks because investors have to defer their rewards, eschewing profits now in the hope of significant growth in the future. A decision that seems sound when there is an expectation that the future holds no additional risks and the alternatives are established, boring (albeit cash-generative) businesses that aren’t likely to grow dramatically from where they are today.

Has this ever happened before?

As the chart shows, the term premium has recorded lows before, particularly in the 1960-70s and the late 1990s-early 2000s. Those two periods were similar to what we’re seeing today, where there were loose money environments that coincided with very frothy market conditions that created a bubble.

Although the term premium did not fall into negative territory, as we’re witnessing now, these extremely loose money environments led to underinvestment by ‘real economy’ businesses, those that make or produce actual things, like energy, paper or cement, while more capital made its way towards ‘new’ economy businesses such as technology.

This cycle of underinvestment in the ‘real economy’ led to lower supply, which led to higher prices, which led to higher inflation.

A similar environment is evident today, as seen by the current energy supply shortages. But we’re facing even greater challenges than previous periods given that we have the added burden of external factors such as transitioning to clean energy to reduce CO2 emissions.

What happens next?

The good news is these cycles eventually unwind, but this can take a long time. For example, on the energy side, it took around 8-12 years in the 1970s to rebuild production and alleviate shortages.

Until that happens, those shortages remain inflationary as low supply and high demand will push prices higher, which in turn drives inflation. Luckily, this metric is a key focus for most central banks and to try and curb inflation rises they will look to tighten the money supply – usually through higher interest rates. This in turn will lead to a more rational term premium as people will start to value money today more highly, leading to a focus on more essential items and capital being allocated more efficiently in the real economy.

What does this mean for investors?

A tighter policy stance from central banks will be negative for asset prices, which means general stock market returns might disappoint. That means stock selection becomes critical.

Currently there is a significant gap between the value and growth stocks in the market. This is because in a loose money environment valuations become dispersed along specific lines and in each of the periods we’ve discussed, this fracture in the market has been between ‘old economy’ and ‘new economy’ businesses.

The willingness of investors to focus on the slim chance of a big future payoff rather than money today, can drive speculative capital into new economy or growth assets that then see the share price rise and their ability to invest in new projects increase. Meanwhile, the reverse is true for businesses whose share prices have been left in the dust, for example, these old economy, lower growth companies. A low share price means they have little incentive to invest in new projects, which affects production and supply.

However, as the term premium returns to normal leading to better rewards for taking on longer-term risk, the situation above should reverse which should see the extreme valuation gap between the value and growth stocks starting to close.

In this type of environment, it’s therefore important that investors understand what a business is worth and what you should pay for it in order to generate satisfactory returns and avoid overpaying for a stock.

This tends to bode well for active stock selection, and more so for value driven investors who can take advantage of this mispricing as they are more focused on the underlying value and fundamentals of a business.

Shane Woldendorp, Investment Specialist, Orbis Investments, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article contains general information at a point in time and not personal financial or investment advice. It should not be used as a guide to invest or trade and does not take into account the specific investment objectives or financial situation of any particular person. The Orbis Funds may take a different view depending on facts and circumstances. For more articles and papers from Orbis, please click here.