After going eight years without a 5% down day, global stockmarkets experienced four in March. It was testament to the extreme fear and uncertainty gripping markets in the face of a truly global health crisis.

In the weeks that have passed since then, the world has remained on edge as countries have extended then relaxed their lockdowns, growth rates have fallen, and unemployment has shot up. Despite this, markets rebounded in April and into May. US stocks experienced their biggest monthly rally since 1987.

We cannot know how this particular crisis will end, or whether the April and May rally will continue or sputter out. What we do know is that at times like this, it is easy to let one’s time horizon shrink. To focus on the immediate priorities. And, while that is undoubtedly important, both from a personal and a financial perspective, it is also at such times that long-term thinking can be greatly rewarded.

The rhyme of history

While there is no denying that the COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented in almost every aspect versus global crises that came before it, the same can be said for each of those crises too. Each one is unique, but there are some lessons that can be learned from them that are helpful to think about now.

The first is that this crisis, like all others, will end. When that will happen and what the world will look like when it does are questions we think through closely, but those questions are hard to answer with any confidence. To us, the first and most relevant question for investors is: Will this company survive the current crisis?

After all, a company’s long-term fundamentals are only meaningful if the company in question is going to be around for the long term. Hoping for a government bailout will most likely be disappointing as a shareholder.

So in a crisis, it is vital to think like a lender and it is why we are far more interested in companies with strong balance sheets and net cash than those with high degrees of leverage.

The second lesson from the past is that crashing markets tend to move in unison, driven on the downside by panic and forced selling, and on the upside by shreds of hope. But, while share prices often move in lockstep, companies’ prospects do not.

No regrets, where is the value now?

In order to work out the difference between those shares that have good reasons to have fallen dramatically and those that are suddenly on sale, we ask ourselves another question:

What will the business be worth over the long term and how does that compare to the current price?

Or said differently, when we look back five years from now, which companies will we regret not having bought at today’s prices?

In some cases, the answer seems clear cut. To us companies like Netease and Tencent should be clear beneficiaries. Both operate online computer games in China and have already seen an uptick in users as people are stuck at home. Looking further ahead, there are other broader considerations. Netease also offers online education services, which could benefit significantly in the long term if the pandemic and the resultant social distancing fundamentally alters education systems. Likewise, Tencent’s remote working business also stands to benefit if the lockdown changes how we learn and work.

Other companies we own are less clear cut. XPO Logistics is, on the face of it, a cyclical trucking and logistics business operating in Europe and America that is feeling the full force of the COVID-19 shutdowns and subsequent economic fallout. The reality is that while some parts of XPO’s business are down significantly, other parts are currently booming. The crisis has laid bare how critical logistics assets are and over time those services will be valued higher by investors and customers. The increase in e-commerce through the crisis is likely to be sticky and this volatility gives a chance for XPO to form closer customer relationships. A crisis like this reveals great management teams and businesses and we believe that XPO has a great management team and is a great business.

Don’t waste a crisis

These longer-term considerations relate to the third similarity that has historically run through investment markets at times of major upheaval—big global events can often accelerate societal change.

'Never let a crisis go to waste' is the mantra of many an astute politician. Caught in the here-and-now of the immediate crisis, big structural changes can sneak by unnoticed. In the wake of the dotcom bust of 2000-01, for example, most people were figuring out which parts of the ‘new’ economy would survive the bust and which elements of the old economy that so many had previously shunned were still relevant. And, as a result, many missed the full import of China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation and the impact it would have on the global economy. Specifically, the natural resources bonanza that was driven by the sharp increase in demand created by its rapidly growing middle class.

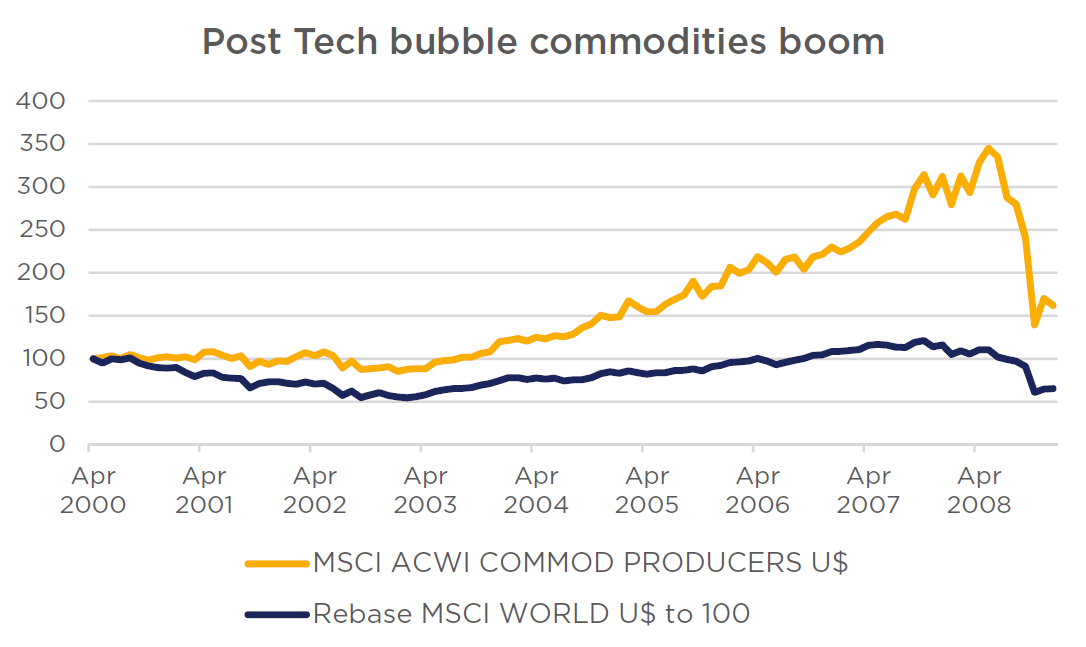

For those that were paying attention, however, there were significant gains to be made in the decade. The graph below shows the performance of a global basket of commodity-producing companies versus the global stock market. Had you invested in just the commodity producers, your investment would have grown more than threefold in the eight years before the GFC, compared to the global market which remained basically flat. Happily, you did not need a crystal ball to profit from the commodities boom in 2000, you simply needed to recognise resource companies were incredibly cheap at the time.

Source: Datastream

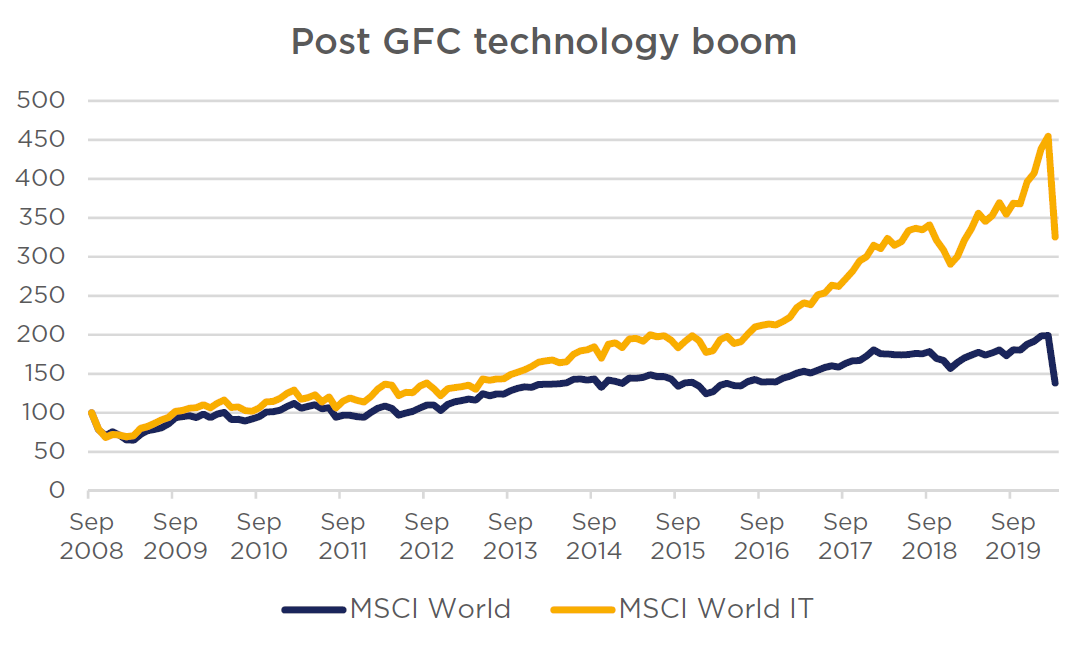

Similarly, in the aftermath of the GFC, instead of debating whether or not to wade back into banks or to stick with something more defensive, the insightful play, as is evident below, would have been to follow the advent of the smartphone, which enabled entirely new business models to emerge and dominate in the 2010s. The next graph, which compares the performance of a basket of global technology shares and the broad market, demonstrates that in the decade that followed the GFC, while the overall market roughly doubled, technology shares increased more than 4½ times.

Source: Datastream

As bottom-up stockpickers, we are not in the business of trying to predict what the next big thing will be. However, the last decade has been incredible for the US stock market and US growth stocks in particular. The next decade could well be about something else altogether.

If there is a clear lesson from previous crises it is that no matter how bad things may be right now, forcing yourself to keep a cool head and focusing on the long term can be enormously valuable.

Charles Dalziell is Investment Director at Orbis Investments, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This report constitutes general information only and not personal financial or investment advice. It does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or individual needs of any particular person.

For more articles and papers from Orbis, please click here.