In the 1970s in the US, a dog food called Alpo was marketed using actor Lorne Greene claiming he personally fed Alpo to his own dogs. Thereafter, the phrase ‘eating your own dog food’ meant using the product you were promoting or marketing. Later, as software applications became more common, the term ‘dogfooding’ became popular with developers to mean using their own software to improve the experience and understand problems users might encounter.

It's appropriate to expect that if a product is as good as a company's marketing says, then the people who work there should use it themselves. By having a consumer experience, or by ‘eating their own food’, they should understand the product and its benefits better.

To what extent do we expect this of company and government executives?

1. Dogfooding in business

There are many versions of dogfooding in business. Or not dogfooding enough. Given the terrible user experience of contacting call centres at banks and communications companies, it’s doubtful many CEOs have phoned their own businesses with a user problem. If they had, they would call their senior staff into a room early next morning and tell them to fix the mess immediately. No executive who goes through a couple of hours of agony on the phone with their own staff should accept the experience. Similarly with websites which only the designers can fathom how to navigate.

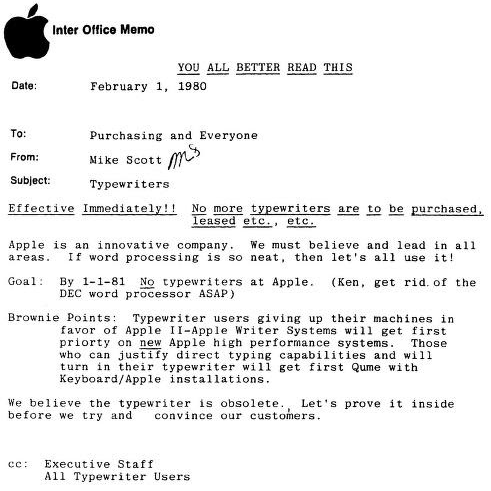

A good example was the initiative by the President of Apple, Michael Scott, in 1980, when word processing and personal computers were in their infancy. An internal memo banned typewriters, as he wrote “We must believe and lead in all areas. If word processing is neat, then let’s all use it!”

Apple’s 1980 internal memo: No more typewriters

That's a great line (was it typed on a WP?): "Let's prove it inside before we try and convince our customers."

Another example is the ride-sharing company, Lyft, which requires all corporate employees to know what it is like to drive a car or service passengers. Salaried staff must spend at least four hours every quarter experiencing what their drivers do, which can include staffing the call centre or working as a Lyft driver.

2. Dogfooding in funds management

If there is one common characteristic every investor wants in fund managers, it is evidence of their ‘skin in the game’. Perhaps in the lucrative world of investing, a better expression is ‘to drink your own champagne’. Fund manager presentations often include a statement about the portfolio managers investing a considerable proportion of their own wealth in their own fund. It shows an alignment of interest, a way to give the investor confidence that the fund manager is working hard for everyone including him or her self.

Morningstar supports this principle as a good signalling factor for investors. For example, Kaustubh Belapurkar, a Director of Fund Research at Morningstar, says:

“We do positively view asset managers encouraging or mandating fund managers to invest in their own funds as a good stewardship practice.”

He cites Royce & Associates, a New York-based fund manager with a policy that lead portfolio managers must invest at least $1 million in their own funds, co-portfolio managers $500,000 and assistant managers $250,000. If they do not have enough money, their bonuses are deferred into the fund.

But such an edict, and our preoccupation with fund managers investing in their own fund, must have its limits.

First, every fund manager, whether or not their own wealth is invested there, wants to do the best for the fund. Should we demand they put everything on the line, including their salary, their bonus, their reputation, their status? Unlike other professions, the performance of a fund manager is on public record at least once a month. A fund manager who underperforms must explain the poor results to everyone, including investors, bosses and the public. It’s already a massive incentive to do well, yet we demand they lose sleep because their personal investments are on the line.

Second, business leaders advocate for the benefits of a more balanced life and hope our agents look after their personal needs, including their family. Like most people, fund managers at a certain time in life will want to buy a good home (yes, we have a tax system that heavily favours home ownership over renting). They should not forfeit this major life event due to a requirement that the majority of their wealth be exposed to their fund.

Third, the fund might not suit the manager’s investment journey. We would not expect a 30-year-old investor to place all their assets in a bond fund, so why expect it from a 30-year-old bond fund manager? It’s just not good investing at such a young age, even if they are a talented manager.

Every investor needs diversification, and for example, a manager running a technology fund is already substantially exposed to growth in that sector without committing all their personal wealth.

We accept when senior executives with large shareholdings in their own companies sell some of their exposures for personal reasons. They might wish to buy a house, pay a tax bill or simply bank some reward for their efforts.

So while alignment is good and expecting a fund manager to have ‘skin in the game’ is desirable, it is given more prominence than is warranted. Every fund manager is desperate for their fund to do well. They don’t need to overwhelm themselves with worry in the process.

Another commitment to the cause by a fund manager is demonstrated by Warren Buffett and his daily consumption of Coke. He bought $1 billion of shares in 1988 then worth over 6% of the company, and it remains a top 3 holding today. He promotes the drink at every opportunity, as he does with many products he has invested in. The Berkshire Hathaway Annual Shareholder meeting is dubbed “Woodstock for Capitalists” as it features discounts and displays for products sold by Berkshire subsidiaries.

3. Dogfooding in government and economic policy

So two basic principles of dogfooding are that we expect:

- business executives to know their products by using them and understanding the consequences of their decisions and feeling the pain if something goes wrong, and

- fund managers to align their interest with ours.

How do these principles apply to politicians and government policymakers?

It’s the opposite. We encourage them to avoid the consequences of their actions by requiring them to disclose personal interests. Apparently, this makes them more 'open and accountable' but in practice it encourages them to be passive in their investing. We expect them to feel little or no impact from the decisions they make. In fact, we don’t seem to want them to have much experience outside their current roles.

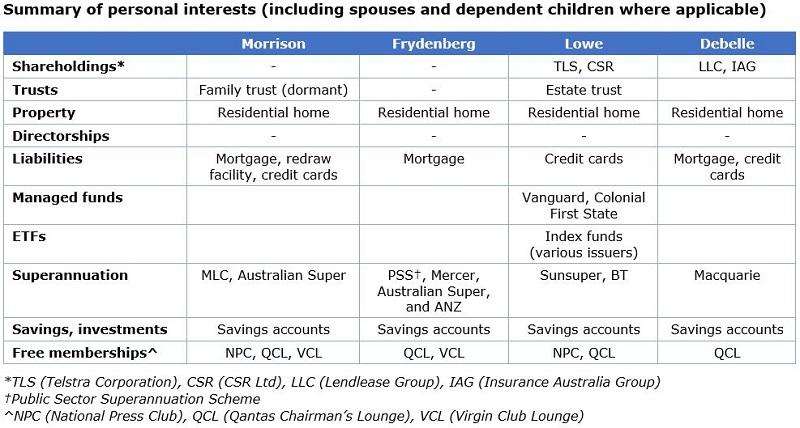

The personal investments of the Governor of the Reserve Bank (RBA), Philip Lowe, and his Deputy, Guy Debelle are on the public record, as advised by the RBA:

“Material personal interests of the Governor and Deputy Governor are published by Reserve Bank. These declarations are made voluntarily to promote openness and accountability.”

It’s the same with Members of Parliament:

“Under the resolution of the House, within 28 days of making and subscribing an oath or affirmation as a Member, each Member is required to provide to the Registrar of Members' Interests a statement of the Member’s registrable interests. The registrable interests of which the Member is aware of the Member’s spouse and any children wholly or mainly dependent on the Member for support must also be included in the statement.”

We know what Scott Morrison, Josh Frydenberg and all MPs own.

Here are the personal interests of these four men, the leading decision makers in our nation.

Source: Australian Parliament website, Reserve Bank of Australia website

The answer to what they invest in is … not much. They seem to have little practical experience in hands-on investing, probably avoiding any perceptions of conflict as we may make them accountable.

The Governor owns his house outright, leaves his superannuation in Sunsuper and BT and outsources some investments to ETFs and managed funds via Vanguard – best known for its index funds - and Colonial First State. His wife owns some Telstra and CSR shares.

It’s a passive investment strategy. Perhaps he has no interest in more active management, is too busy or he simply believes in an efficient market and an inability to beat the index after fees. Funds are heavily marketed and he might not buy the story. He does not appear to hold any investments such as bonds, alternatives or investment property directly.

Guy Debelle is similar, although he still has a mortgage. He has no managed funds or ETFs, but his wife has investments in Lend Lease and IAG.

Our Prime Minister and Treasurer are the same, with no investments on their records. Both have a mortgage but their wives own nothing.

All four are members of the prestigious Qantas Chairman’s Lounge, and the politicians also enjoy hospitality from Virgin. They even need to declare flight upgrades.

Should they have more investing and business experience?

It’s not the typical experience of most people who have reached a position of power and accumulated considerable assets. No SMSFs in here.

Lowe and Debelle guide the RBA in its policy settings. The RBA’s duty includes “the economic prosperity and welfare of the Australian people”. It conducts monetary policy by “working to maintain a strong financial system.” Both are required to make judgements on the impact of their policies on Australians while maintaining a strong financial system. When they make speeches about market conditions, everyone listens as if the voice of great experience is speaking.

While they are highly regarded in policy formulation and reading conditions in the economy, they have little ‘skin in the game’ experience. We seem to prefer it that way.

Lowe joined the RBA in 1980, straight from university. That’s over 40 years in one place, never in business. Debelle joined the RBA in 1988 from Treasury and his time has included stints at the International Monetary Fund and Bank for International Settlements. Like Lowe, he has no business experience.

Lowe might be accused of self-interest if he owned five investment properties with large mortgages when he lowered interest rates. Yet he seems to have a lot of cash and nobody will accuse him of self-interest when he raises rates.

While Frydenberg spent some time as a lawyer after university, he went into politics without hands-on business experience, and Morrison was in tourism before politics.

Of course, allowing such leaders to invest in major companies introduces potential conflicts. For example, the recent decision to provide taxpayer funding to Ampol to keep its Lytton refinery open led to a 9% rally in Ampol's share price. It would not look good if a political decision-maker on the subsidy were a shareholder.

But plenty of politicians go on to work in the private sector after their parliamentary careers, and we will never know what arrangements were made before they left office. They also become lobbyists for clients in the same industries where they were once ministers. While in office, they do favours for political donors, often for land deals and property developments, or for media supporters. There are major infrastructure projects for dubious benefits and multi-million consulting contracts to provide government services.

Compared with these potential conflicts which never make it onto a personal conflict register, owning a few shares in a company seems a trifle.

Why do we want dogfooding in business and investing but not in government?

There is no doubt Lowe and Debelle make decisions in the genuine best interest of the country, so why don't they own more investments?

We not only allow fund managers to invest in their own funds but we demand it. We expect businesses to use their own products to learn the experience as a customer, and we remunerate executives with company shares.

But for some reason, we do not expect policymakers to know what it’s like to run a business, to fire staff when cashflow dries up, to lose a rental tenant, to agonise over a fall of 50% in the sharemarket and to more fully understand the consequences of their decisions. Why do government members have so little experience outside their current roles?

At least it means you can readily invest like the Governor of the RBA or the Prime Minister of the country. Just whack your super in a fund and buy some ETFs.

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Firstlinks.