Now that the question of when the US Fed will increase interest rates is answered, the next big question for global markets is how far will they increase rates?

The challenge for those trying to forecast the Fed’s actions in 2016 and beyond is that we are in unchartered waters. Rates have never been at zero before, and the Fed has never increased rates when both inflation and economic growth are so weak.

Fed needs to avoid destabilising

The financial market turmoil in recent weeks adds weight to the argument for the Fed to be more patient. Markets are clearly nervous about global growth, whether it’s in China, Japan or Europe, and the news isn’t bright from any part of the world. Any move by the Fed seen to be constraining for the world’s strongest economy, the US, has the potential to destabilise financial markets further. While the Fed’s mandate doesn’t require them to manage financial markets, any major corrections have the risk of spilling over into the real economy by damaging confidence.

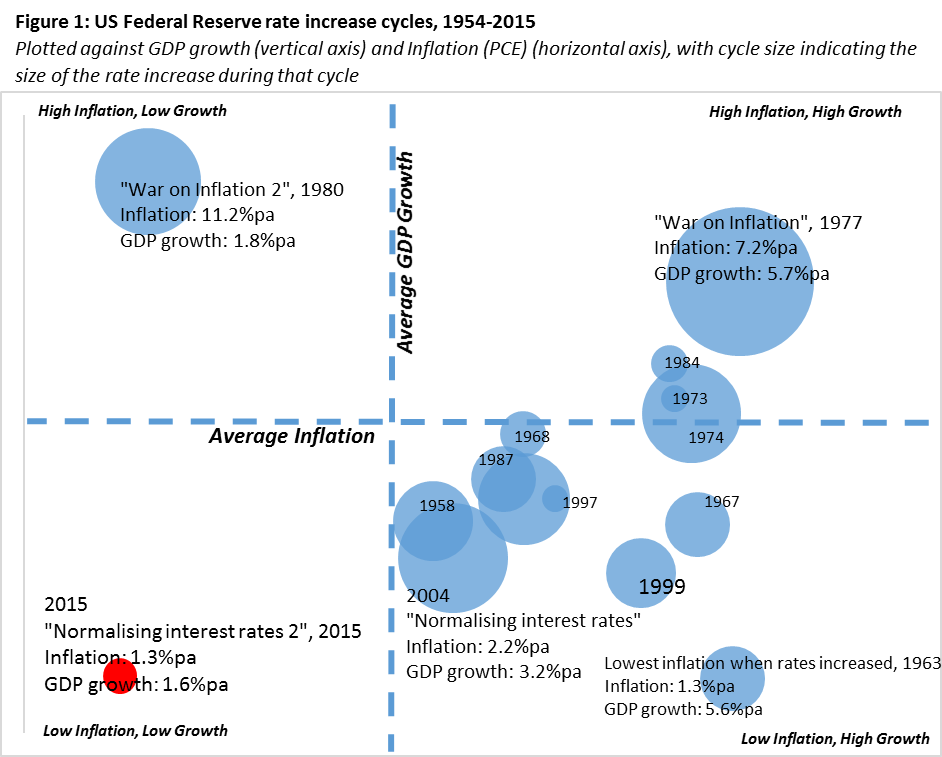

The chart below highlights how different 2016 is to any other interest rate increase cycle. The chart plots each US Fed hiking (increasing) cycle against the inflation and GDP growth figures at the start of that cycle. The larger the circle, the larger the rate increase during the cycle.

What’s happening this time?

The 2015 cycle, kicked off with the rate increase in December 2015, is the only cycle in which both inflation and growth are below average. In fact, growth is lower than the only other cycle in which the Fed has increased rates despite below average growth: the 1980 war on inflation in which inflation was running at 11.2%. And inflation is equal to the lowest of any cycle, but in the other cycle, growth was running hot at 5.6% and so inflation was a significant risk.

So this time it is different. There are two strong arguments suggesting the Fed won’t be in a hurry to increase rates:

1. A weak global economy and raging currency wars

The global economy is weak, and getting weaker. China is clearly slowing, and possibly more than their official data states. The EU and Japan are caught in a multi-decade trap of falling population and imposed fiscal austerity due to their high debt. All three economies are engaging in a currency war in an attempt to make their exports more attractive and boost their economies.

China’s weapon is to lower interest rates to make their currency less attractive, and then devalue their currency. Japan and the EU have zero interest rates already, so they are using massive Quantitative Easing programs to keep longer term rates lower and also make their currencies unattractive.

Lowering one’s currency to make exports attractive works well unless everyone else does it too. Every currency is falling against the US. This puts enormous pressure on the US economy as it weakens their export competitiveness.

This leaves the US Fed in a risky predicament. If the Fed raises rates too quickly or too far, the USD will escalate even further. The Fed will obviously be acutely aware of this and so they will only raise rates further if they have to due to inflation rising above their 2% pa target level.

2. Weak inflation outlook

Central banks’ role is to maximise employment while keeping inflation at or below a stated target level. The Fed’s target rate of inflation is 2%, and it prefers “Core PCE” as a measure of inflation, which is the increase in personal consumer expenditure items excluding food and energy. Using this measure, US inflation is just 1.33% as at December 2015. Add back food and energy, and it is just 0.39%.

Typically, the signal of future inflation risks is wage inflation, i.e. rising wages will typically occur before goods and services’ prices are increased. Wage inflation typically follows a labour market reaching the point at which employers have to compete for labour.

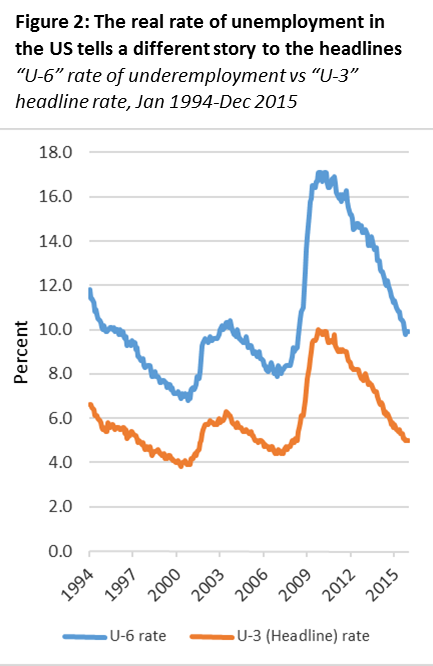

Many commentators have forecast for US inflation to jump in 2015 as the rate of unemployment is well below historic averages. This analysis is flawed as they are looking at the ‘U-3’ measure of unemployment, the measure used in the media headlines and currently 5.0%. But ‘U-3’ simply measures those people without any job, but doesn’t count those in part-time employment that want more hours, or those working for a ‘lesser’ job but seeking better work.

‘U-6’ includes this group and provides an indication of the pool of labour available before employers have to compete with each other for employees and therefore increase wages they are prepared to pay.

‘U-6’ is still well above long-term averages. ‘U-3’ below average simply means that while more people than usual have a job, there is a large proportion of the economy seeking more or better work, and therefore still a lot of slack in the economy.

Without pressure to increase rates, and with the currency wars underway globally, the Fed will be patient. Patience can be interpreted to mean increases will be slow and only if necessary. Looking at historic rate increases, there is no pattern or rule that says the Fed is obliged to increase more than once.

Given we are coming off zero interest rates, it is reasonable to assume that they will want to raise at least 3-4 times during this cycle to give some space to ease again if they have to, but there is nothing to stop them from pausing or even reducing rates along the way. This cycle will be very long and very flat.

Craig Swanger is Senior Economist at FIIG Securities Limited, a leading fixed interest specialist. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.