With a backdrop of the Financial Services Royal Commission and a cooling property market, Australian investors are understandably looking to diversify from the bank-dominated ASX/S&P 200 Index.

Yet risks also abound offshore with interest rates rising after years of low real rates, inflation is inching higher and equities appear more expensive after a strong decade-long run.

So how does an investor navigate this environment?

While equity valuations are stretched, they are more attractive investments than fixed income securities and direct (unlisted) investments such as property and infrastructure. These asset classes could face even greater risks in an interest rate tightening environment.

There are, however, segments of the equity market that are trading at extreme valuations and that is where the greatest risk lies.

The Golden Rule

Why do we think these valuations are extreme and not just the 'new normal' as some commentators have said? A problem is that the market is pricing in low rates into perpetuity, while also maintaining heroic growth assumptions. This represents a theoretical mismatch. Why so?

Any company valuation essentially has two parts:

- Earnings or cash flows (the numerator)

- The multiple or discount rate, usually P/E (the denominator)

This is the basis for what we refer to as the 'Golden Rule' of equity investing. The Golden Rule is: In the long run, nominal GDP growth should correlate with nominal long-term interest rates. In other words, in the long run, there must be a link between the numerator (earnings growth or cash flow) and the denominator (the multiple or discount rate).

In times of heady investment markets, like today, we often see investors break this Golden Rule and build heroic growth assumptions without applying higher interest rates. In our view, there are only two alternatives: either growth will be higher and rates will rise, resulting in a higher discount rate and lower valuations; or growth will be structurally lower and earnings will come down.

The earnings side of the equation

The expansion in price to earnings ratios (P/Es) and other metrics in certain areas of the market is not what concerns us the most. We are also concerned about the risk of inflated earnings of some companies, or the ‘E side’ of the equation.

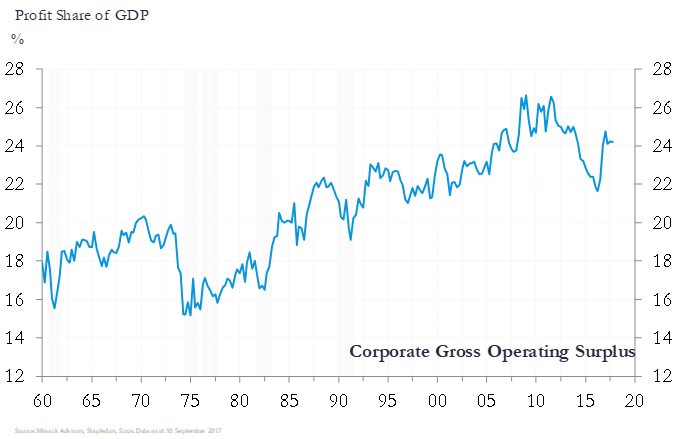

Profits as a percentage of the economy are now high by historical standards (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1 – Profit share of GDP

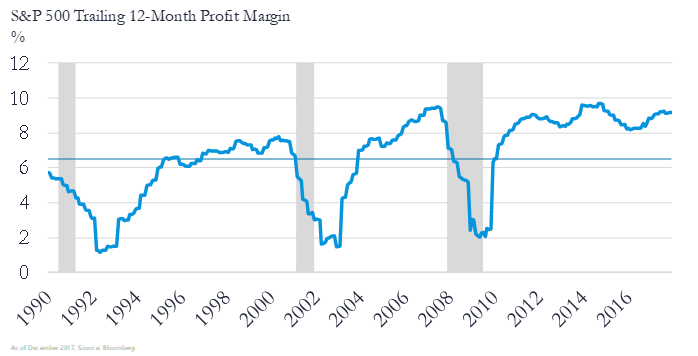

Corporate profit margins are expanding and are well above long-term averages (Exhibit 2). In our view, for most companies this margin growth is unsustainable in the long term. Ultimately, we believe profit margins over the long term will decline, either through slower sales growth (associated with lower GDP) or higher input costs (wages and cost of funding via higher interest rates). We believe this has the potential to dramatically impact some companies, particularly those with both high margins and a high P/E multiples.

Exhibit 2 – Corporate profit margins rising

A better guide is the Shiller P/E

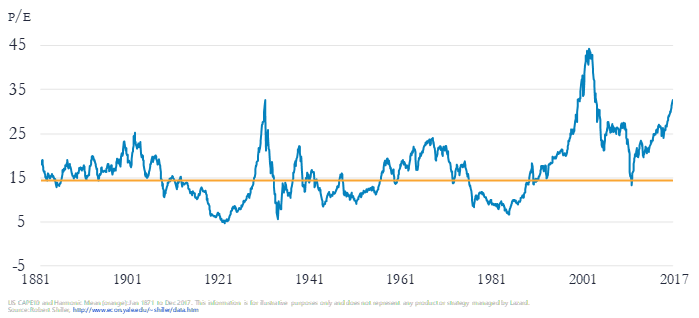

To put market valuations in an historical context, we think the Shiller P/E acts as the best guide. Standard P/E uses the ratio of an index over the trailing 12-month earnings of its constituent companies. During economic expansions or bull markets, companies can have inflated profit margins and earnings and the P/E falls as a result.

The Shiller P/E eliminates fluctuations caused by the change in profit margins during different business cycles. Currently, the Shiller P/E is at a level only reached three times in history, the others being in 1929 and in 2000 (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3 – US 10-year cycle-adjusted P/E

What to avoid

We primarily see two main risks for investors:

1. Companies with unsustainably high margins

We are concerned about some companies’ rapidly rising profit margins, which lead to expanded earnings, and the hefty multiples paid for their stocks. It is dangerous to assume these companies can maintain such profitability into the future and an investor needs to understand how sustainable the current level of profitability is.

This sustainability is particularly important should the economy soften. The ability to generate stable margins is actually quite rare, particularly in times of economic dislocation.

2. Expensive defensives

The prolonged low-interest rate environment has driven investors to seek out bond proxies: companies that have a combination of relatively attractive dividend yields and stable earnings. Consumer staples companies are the classic case, as are other traditional safe havens such as North American utilities and global REITs.

In consumer staples, the growth rates required to justify current share prices are substantial, which contradicts the sluggish revenue growth most of these companies are actually experiencing today. We believe either rates will rise, making these stocks less appealing, or growth rates will disappoint, bringing multiples down.

Where to go?

As the investment environment normalises, investors must adapt their portfolios to achieve their return target. Generating an adequate return from global equities will not be as easy as in the past. Now investors need to:

- Focus on the right companies, such as higher quality names with more predictable earnings.

- Focus on valuation, and invest in the right companies but only at the right prices.

- Diversify sensibly, not naively. A widely diversified portfolio perversely may be more risky than a concentrated portfolio given the overall level of risk in equity benchmarks.

- Expect currency exposure to play a major role in the performance process.

We expect a greater spread between the small number of winners and the larger number of losers. Risk should be defined as the probability of a permanent loss of capital, and, in the environment we face today, that risk is coming into sharper focus.

Warryn Robertson is a Portfolio Manager and Analyst at Lazard Asset Management. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.