When Howard Marks speaks, investors listen. Marks is well known to regular Firstlinks readers as the Co-Chairman of Oaktree Capital Management, which he co-founded in 1995 and is the world's largest distressed debt investor. He’s written two books and is best known for his client memos published since 1990.

In his latest memo and interview, Marks outlines how today’s markets are dramatically different from those of the past 40 years, that equity valuations are mildly expensive, and the most compelling opportunities for investors in 2024.

When the good times rolled

Marks says that almost everyone working in finance today had only ever seen interest rates go down ... until 2021:

“You have to be working in this business more than 43 years, before 1980 to have ever seen anything other than declining interest rates and ultra-low interest rates. So it’s only natural to conclude that declining and ultra-low interest rates are normal.”

But he says that period was anything but normal, especially from 2008-2021, when reserve banks dropped interest rates to ultra-low levels. He says that resulted in “easy times, fueled by easy money”.

He details the effects of low interest rates, including:

- Stimulating the economy

- Lifting asset prices

- Encouraging risk taking and potentially unwise investments

- Enabling deals to be financed easily and cheaply

- Encouraging greater use of debt

- Fueling expectations of continued low interest rates

- Producing winners and losers by subsidizing borrowers at the expense of savers and lenders

In sum, ultra-low rates made it easy to run a business, easy for investors to enjoy asset appreciation, easy to lever investments, easy for businesses to get loans, and easy to avoid default and bankruptcy.

End of an era

Marks believes that many investors are counting on a return to this period of ultra-low rates. Yet he thinks that era is over.

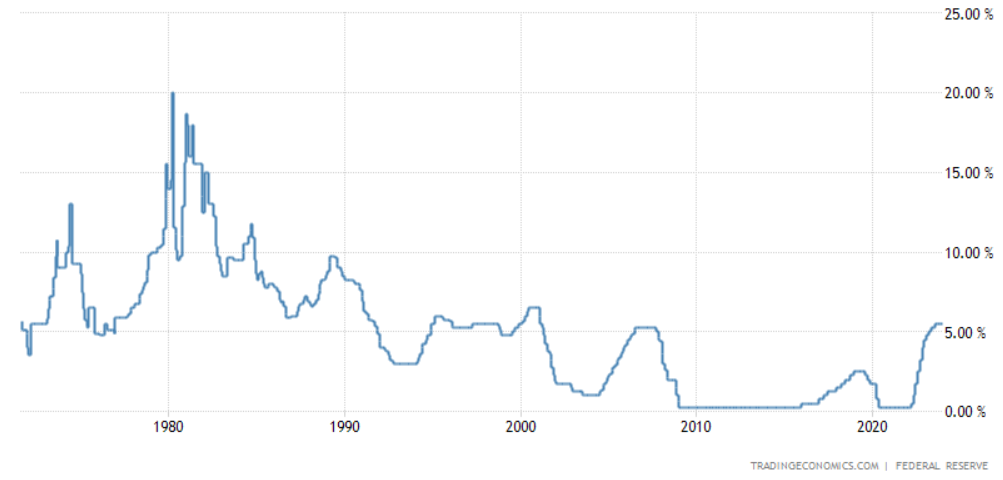

First, he dismisses concerns that today’s rates are high. He says while rates are higher than they’ve been in 20 years, they aren’t high in absolute terms or relative to history. He recounts how when he started work in 1969, the Fed funds rate averaged 8.2%. In the 20 years after that, the rate ranged from 4% to 20%. From 1990-2000, the last period that Marks thinks was ‘normal’, the rate was between 3% and 8%, suggesting a median equal to today’s rate of 5.25-5.5%.

Fed Funds rate

Marks then addresses why we’re unlikely to go back to ultra-low rates any time soon. His reasons include de-globalisation, the Fed wanting to prevent another bout of inflation, central bankers wanting enough room to cut rates if there’s an economic downturn, as well as avoiding further assets bubbles, malinvestment and creating economic winners and losers.

Future rate predictions

Marks outlines where he believes market consensus sits today:

- Inflation will soon reach the Fed’s target of roughly 2%.

- Therefore, additional rate increases won’t be necessary.

- Consequently, there’ll be a soft landing marked by a minor recession or none at all.

- The Fed will be able to take rates back down.

- This should spur the economy and the stock market.

He doesn’t directly disagree with this consensus view, though questions it. Even if the consensus is right, Marks predicts that US rates will be around 2-4% over the next few years. And that if he had to be more specific, that rates will average 3-3.5% over the next 5-10 years.

Investors need to adapt to a new environment

One of Marks’ big themes is that investors need to adapt to a new investment environment where rates don’t go down to ultra-low levels. Yet changing ingrained habits is difficult:

“Well, if you made money doing one thing over the last 43 years, it’s kind of hard to say, “You know what? That’s out the window.” And that organization that I put together, I got to get rid of those people because I need a new skillset. Everything I ever told you is no longer true to the clients. This is complicated by our human nature, if that’s the right term. But I’ve been making reference to a book Mistakes Were Made, But Not by Me by Carol Tavris. It’s about cognitive dissonance and self-delusion. And you have a position, you’ve had it for a while, you’re convinced it’s right, it has worked. And now you get some information coming in which says, “No, you have to change your position.”

But Marks says only by changing strategies can investors expect to outperform in future. And he says that “if you grant that the environment is and may continue to be very different from what it was over the last 13 years – and most of the last 40 years – it should follow that the investment strategies that worked best over those periods may not be the ones that outperform in the years ahead.”

Equity valuations are somewhat expensive

I find one of Marks’ best attributes is to take the temperature of markets in an objective and balanced way. While many investors try to grab headlines with black and white, or extreme views, Marks is usually more nuanced.

His latest views on equities reflect this. Marks thinks the US market is neither crazily high nor low, and that it doesn’t offer a 'fat pitch’, which harks back to a famous Warren Buffet saying:

“I call investing the greatest business in the world because you never have to swing. You stand at the plate, the pitcher throws you General Motors at 47! U.S. Steel at 39! and nobody calls a strike on you. There’s no penalty except opportunity lost. All day you wait for the pitch you like; then when the fielders are asleep, you step up and hit it.

… Wait for a fat pitch and then swing for the fences.”

Marks thinks the US stock market is about 10% overvalued and at these levels it could go in any direction from here. The “fact that it’s 10% overvalued means that there’s a slightly greater tendency than usual for it to go down rather than up. But the point is not enough to take action on. I feel the same way about the economy.”

Compelling investment opportunities

Marks is more bullish on debt than equity:

“… you can potentially get equity type returns from credit with less risk in better companies than used to be the borrowers with less leveraged companies than used to be the borrowers. And these returns, whether they’re approaching 10 for liquid credit or above 10 for private credit, these are fully competitive with equities more than most people need, and they can be earned with greater safety than with equities. So I continue to think that the opportunity is compelling.”

Marks’ colleague, David Rosenberg, a co-portfolio at several of Oaktree’s credit-focused funds, goes further, suggesting debt is one of the best trades that he’s seen in his career, as “what we have right now, which is so unique, is the market is handing investors this opportunity to say, “I can sell my equities and go buy debt, which is bringing my risk meaningfully down, but actually preserve the same expected return.” … In the investment world, we call this a no-brainer, this trade. The ability to bring your risk down without having to meaningfully impact your expected return is very valuable and something that’s really, really exciting.”

James Gruber is an assistant editor at Firstlinks and Morningstar.com.au