The word ‘bubble’ is thrown around in investment circles on a regular basis, but billionaire investor Howard Marks can lay some claim to literally writing the memo on bubbles. In January 2000, exactly 25 years, he wrote what he calls a memo (ie. an investor letter) called ‘bubble.com’ and the subject was the irrational behaviour he thought was happening in tech and e-commerce stocks at that time. The memo garnered much attention because it proved right, and right quickly.

The tech-media-telecom bubble was the first of two spectacular bubbles in the 2000s. The second was the housing bubble and subsequent banking crisis of 2008.

Having been through these periods, many investors are on heightened alert for bubbles, and Marks is often asked about whether today’s market represents the third major bubble of this century.

Are we in a bubble now?

First, Marks goes through some familiar facts on the ‘Magnificent Seven’ stocks (Microsoft, Nvidia, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, and Tesla) and their impact on markets, including:

- The stocks represent around 33% of the S&P 500 Index;

- That’s roughly double their share of the index five years ago; and

- Prior to the Magnificent Seven, the highest share for the top seven stocks over the past 28 years was 22% in 2000.

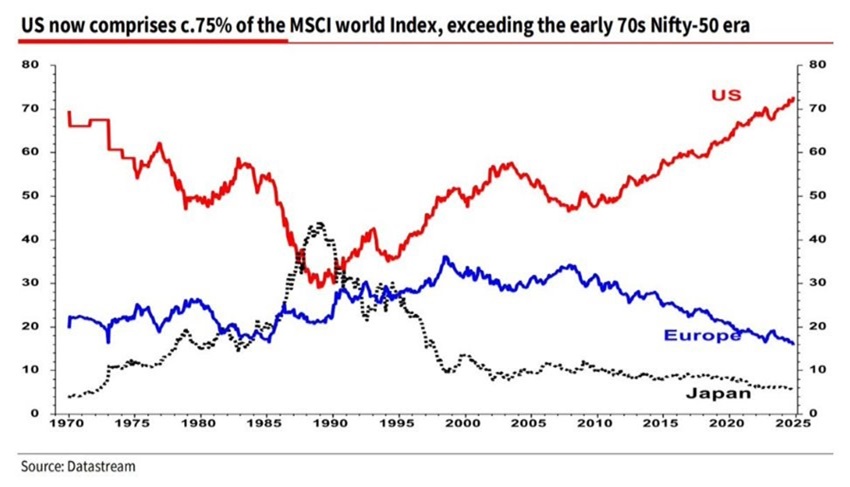

The rise of the Magnificent Seven has resulted in US stocks being 75% of the MSCI World Index, the highest percentage since 1970.

The big question is: is this a bubble?

What is a bubble?

Marks initially steps back to ask what a bubble is. For him, it’s “more a state of mind than a quantitative calculation”. He says a bubble isn’t just about rising share prices, but is a temporary mania characterised by:

- Highly irrational exuberance

- Adoration of the subject companies or assets, and a belief that they can’t miss

- Massive fear that you’ll miss it if you don’t invest in the companies ie. FOMO

- Conviction that there’s no price too high for said stocks

Mark suggests the final point is critical. Investors can’t imagine any flaws in arguments to buy the stocks and are terrified they’ll be left behind by those who do purchase the shares.

Therefore, Marks thinks bubbles aren’t just about valuations; they have a psychological element. He quotes from Charles Kindleberger’s seminal book, ‘Manias, Panics and Crashes’:

“… As firms or households see others making profits from speculative purchases or resales, they tend to follow. When the number of firms and households indulging in these practices grows larger, bringing in segments of the population that are normally aloof from such ventures, speculation for profit leads away from normal, rational behaviour to what have been described as “manias” or “bubbles.” The word “mania” emphasizes the irrationality; “bubble” foreshadows the bursting. (Emphasis added)”

Bubbles can sometimes be recognised through anecdotal evidence, such as when J.P Morgan knew there was a problem when the person shining his shoes started giving him stock tips.

How bubbles form

The question Marks then addresses is what it is that makes investors behave irrationally. The first thing that he identifies is ‘newness’ or the ‘this time is different’ phenomenon.

Bubbles are invariably associated with new developments. Historical examples include:

- The 1630s craze in Holland over recently introduced tulips

- The 1720 South Sea Bubble in England over a trading monopoly that the Crown had awarded to the South Sea Company

- The Nifty Fifty stocks in the 1960s

- TMT/internet stocks in the late 1990s

- Subprime mortgage-backed securities in 2004-2006

Marks says that normally if a company or country’s shares are at unusually high valuations, people can point to history to act as a tether to temper the enthusiasm.

However, “if something is new, meaning there is no history, then there’s nothing to temper enthusiasm” and when “a whole market or group of securities is blasting off and a specious idea is making its adherents rich, few people will risk calling it out.”

The second aspect that Marks believes forms a bubble is a belief among investors that things can only get better. The attractions of a new product or way of doing business are obvious, yet the pitfalls are often hidden and are therefore ignored.

He says the trick with bubbles is that there’s usually a grain of truth which underlies them; it just gets taken too far.

This can result in investors treating all contenders in a new field as likely to succeed and assigning them valuations assuming success. Though only a few may thrive, or even survive.

It can also lead to investors adopting a ‘lottery ticket mentality’, thinking a startup in a hot industry could return 200x, then it’s worth investing in even if there’s a 1% chance of success. Thinking this way, there are few limits to what investors will pay for these stocks.

“Obviously, investors can get caught up in the race to buy the new, new thing. That’s where the bubble comes in,” Marks says.

Valuation also comes into play

As a value investor, Marks is loath to ignore the role of valuations in a bubble. He makes a great point of a common misunderstanding when it comes to the most used valuation metric, the price to earnings (P/E) ratio. The price of the S&P 500 has averaged around 16x earnings over the past 80 years. Marks says it’s typically described as, “you’re paying for 16 years of earnings.” He says it’s more than that, because the process of discounting makes $1 of profit in the future less than $1 today. A 16x P/E ratio is really more than 20x (depending on the discount rate used for future earnings).

Marks says that in bubbles, stocks sell for far more than 16x earnings. For instance, Nifty Fifty companies in 1969 sold for 60 to 90 P/E ratios.

The good news is that Mark believes today’s Magnificent Seven are far superior companies to those involved in past bubbles. They have huge scale, dominant market positions, and high margins.

And their valuations aren’t as steep as the Nifty Fifty companies. For example, Nvidia’s forward P/E ratio is in the low 30s.

The problem of remaining on top

Marks does see an issue with P/E ratios in the low 30s, though. He says it assumes that Nvidia (NYSE:NVDA) will be in business for decades to come, that its profits will grow over decades, and that it won’t be overtaken by competitors. He says, “investors are assuming Nvidia will demonstrate persistence.” In other words, that Nvidia will remain on top for a long time to come.

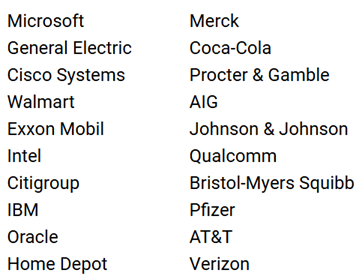

History demonstrates that this will be hard to achieve, according to Marks. He points out that that the following companies were in the top 20 in 2000:

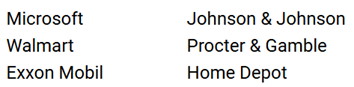

Of these, only six remained in the top 20 by the start of 2024:

It’s worth noting that this list is now down to five companies with Johnson and Johnson NYSE:JNJ) slipping out, while Walmart (NYSE:WMT), Home Depot (NYSE:HD), and Proctor & Gamble (NYSE:PG) are just hanging on to 18th, 19th, and 20th places in the S&P 500.

It’s also worth noting that of the Magnificent Seven, only Microsoft was in the top 20 in 2000.

Marks suggests that in bubbles, “investors treat the leading companies – and pay for their stocks – as though firms are sure to remain leaders for decades. Some do and some don’t, but change seems to be more the rule than persistence.”

And in bubbles, Marks says that they initially are concentrated in a small group of stocks, though that can extend to whole markets as the fervour spreads.

Where do today’s markets stand?

With this background, Marks turns his attention to the current market. He points to the obvious: that the above average returns of the past two years can’t last forever. After all, US corporate profits increase by an average 7% per year. For the S&P 500 to rise more than 20% as it’s done over the past two years, is unusual and can’t go on forever.

He says there are only four times in the history of the S&P 500 when it returned 20% or more, and in three of those four instances, the index declined in the subsequent two-year period. The exception was 1995-1998 when the TMT bubble formed, only to burst in 2000.

So, what about the future?

Marks lays out several cautionary signs including:

- The optimism that has prevailed in markets since late 2022

- The above average valuation of the S&P 500, and that US stocks in most sectors sell at much higher multiples to comparable stocks in the rest of the world

- The enthusiasm for a new thing in AI

- The presumption that the Magnificent Seven will continue to be successful

- The possibility that the rise of the S&P has been aided by ETFs that automatically purchase stocks, without regard to valuation

- The 465% rise in the price of Bitcoin over the past two years “doesn’t suggest an overabundance of caution.”

He also outlines the counterarguments:

- The P/E ratio of the S&P 500 is high but not insane

- The Magnificent Seven are magnificent companies and their steep valuations may be warranted

- He doesn’t hear investors saying “there’s no price too high”

- The markets, while high-priced and perhaps frothy, don’t seem nutty

(As an aside, I disagree with Marks on point three: I have heard this with the Magnificent Seven, as well as with Australian stocks such as Commonwealth Bank (ASX:CBA), Pro Medicus (ASX:PME), and WiseTech Global (ASX:WTC). In fact, I read a recent stockbroker note which essentially said that Pro Medicus was a buy, no matter what the price.)

What’s the final verdict?

Though Marks doesn’t say it, I think he believes that though the US market is expensive and exhibits some signs of irrational exuberance, it doesn’t constitute a bubble in his eyes. But it’s not to say that it won’t become a bubble in future.

James Gruber is Editor at Firstlinks.