The period August to October is a time for anniversaries of financial market crises – the 1929 share crash, the 1974 bear market low, the 1987 share crash, the emerging market/LTCM crisis in 1998, and of course the worst of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. The GFC started in 2007 but it was the collapse of Lehman Brothers on 15 September 2008 and the events around it which saw it turn into a major existential crisis for the global financial system. Naturally each anniversary begs the question whether it can happen again and what the key lessons are. And so it is with the 10th anniversary of the worst of the GFC.

A brief history of the GFC

The GFC was the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. It saw the freezing of lending between banks, multiple financial institutions needing to be rescued, 50% plus share market falls and the worst post-war global economic contraction. Low interest rates prior to the GFC saw too many loans made to US homebuyers that set off a housing boom that went bust when rates rose and supply surged. Specifically:

- About 40% of loans went to people with a poor ability to service them – sub-prime and low doc borrowers. And many were non-recourse loans so borrowers could just hand over the keys to the house if its value fell.

- This was encouraged by public policy aimed at boosting home ownership and ending discrimination in lending. Some extolled the 'democratisation of finance'.

- It was made possible by a huge easing in lending standards and financial innovation that packaged the sub-prime loans into securities, which were then given AAA ratings on the basis that while some loans may default the risk was offset by the diversified exposure. These securities were then leveraged, sold globally and given names like Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs). But after securitisation there was no 'bank manager' looking after the loans.

- Banks were sourcing an increasing amount of the money from global money markets.

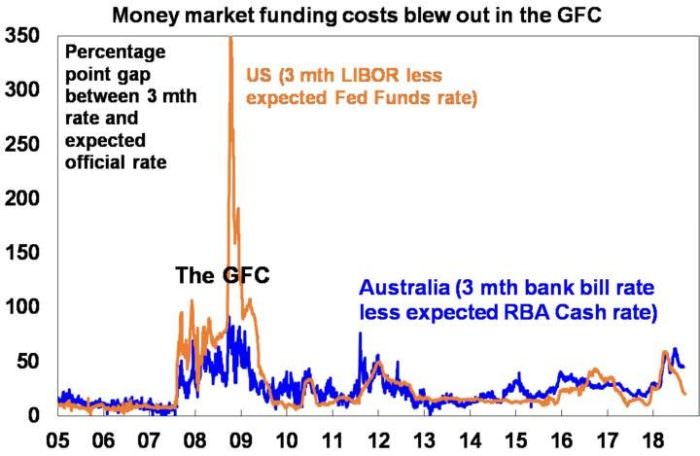

This stopped in 2006 when poor affordability, an oversupply of homes and 17 Fed interest rates hikes saw US house prices slide. Sub-prime borrowers struggled to refinance loans after their initial 'teaser' rates so they started defaulting, causing losses for investors. In August 2007, BNP froze redemptions from three funds because it couldn’t value the CDOs within them, triggering a credit crunch with sharp rises in the cost of funding for banks. See the surge in short-term borrowing rates relative to official rates in the chart. A reduction in credit availability initially caused sharp falls in share markets.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

Shares rebounded but peaked around late October 2007 before falling about 55% as the credit crunch worsened, the global economy fell into recession and many banks failed with a big one being Lehman.

The crisis went global as losses magnified by gearing mounted, forcing investment banks and hedge funds to sell sound investments to meet redemptions which spread the crisis to other assets. The wide global distribution created a loss of trust resulting in a freezing of lending between banks and sky-high borrowing costs which affected confidence and economic activity.

The GFC ended in 2009 after massive monetary and fiscal stimulus along with government rescues of banks, but aftershocks continued for years with sub-par growth and low inflation into this decade. From an economic perspective the GFC highlighted that:

- Fiscal and monetary policy work. There is a role for government, central banks and global cooperation in putting free market economies back on track when they go into a downward spiral. While some have argued that easy money just benefitted the rich, doing nothing would have likely ended with 20% plus unemployment and worse inequality.

- The return to normal from major financial crises can take time. The blow to confidence depresses lending and borrowing and hence consumer spending and investment for years afterwards. The key is to allow for this and not turn off the policy stimulus prematurely, but also to avoid thinking it is permanent as the muscle memory does eventually fade.

- 'Stuff happens'. After each economic crisis there is a desire to make sure it never happens again, but history tells us that manias, panics and crashes are part and parcel of the process of creative destruction that has led to an exponential increase in material prosperity in capitalist countries. The trick is to ensure that the regulation of financial markets minimises the economic fallout that can occur when free markets go astray but doesn’t stop the dynamism necessary for economic prosperity.

Will it happen again?

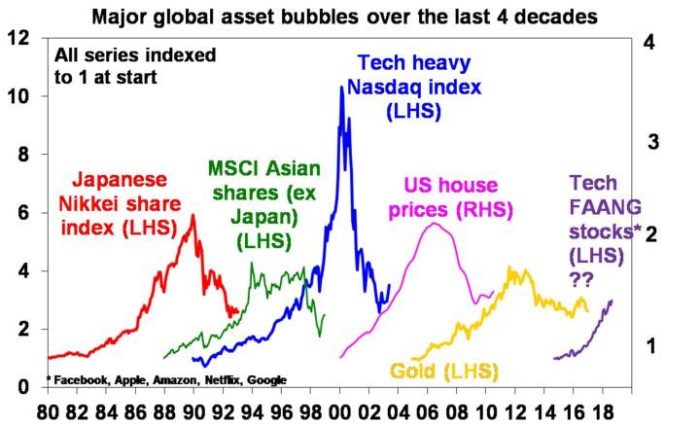

History is replete with bubbles and crashes and tells us it’s inevitable that they will happen again as each generation forgets and must relearn the lessons of the past. Often the seeds for each bubble are sown in the ashes of the former. Fortunately, the post-GFC environment has seen an absence of broad-based bubbles on the scale of the tech boom or US housing/credit boom. There was a brief surge in gold and some commodity prices early this decade but it did not become too big. Bitcoin and other cryptos blew up before sucking in enough investors to have a meaningful global impact. E-commerce stocks like Facebook and Amazon are candidates for the next bust but they have seen nowhere near the gains or infinite P/E ratios seen in the late 1990s tech boom.

Source: Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg, AMP Capital

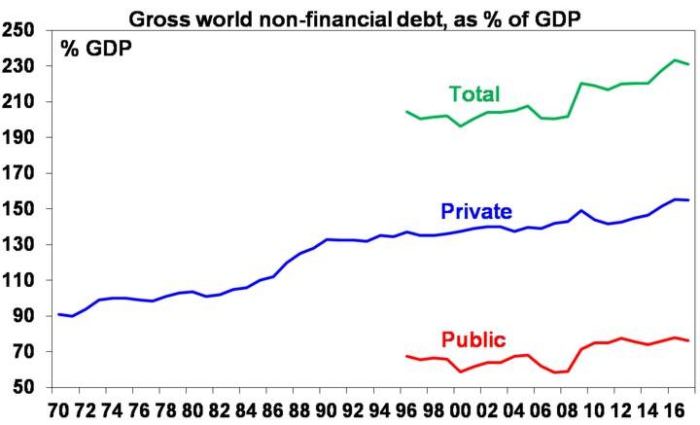

Post GFC, global debt has grown to an all-time high relative to global GDP, but this alone does not mean another GFC is upon us. The ratio of global debt to GDP has been trending up forever, much of the growth in debt in developed countries has been in public debt and debt interest burdens are low thanks to still low interest rates. Other signs of excess like those in the GFC are not present on a widespread basis. Inflation is low, monetary policy globally remains easy, there has been no widespread overinvestment in technology or housing.

Source: IMF, Haver Analytics, BIS, Ned Davis Research, AMP Capital

Banks are required to have higher capital ratios and raise more funds from their depositors. Much of the surge in debt post the GFC has been in private emerging market debt rather than in developed countries suggesting emerging markets are at greater risk. Another economic crisis is inevitable at some point, but it will likely be different from the GFC.

Seven lessons for investors from the GFC

The key lessons for investors from the GFC are:

1. There is always a cycle. Talk of a 'great moderation' was all the rage prior to the GFC but the GFC reminded us that long periods of good growth, low inflation and great returns are invariably followed by something going wrong. If returns are too good to be sustainable they probably are.

2. While each boom-bust cycle is different, markets are pushed to extremes. The asset at the centre of the upswing becomes overvalued and over-loved at the top and undervalued and under-loved at the bottom, which for credit investments and shares was in first half of 2009. This provides profit opportunities for patient contrarian investors.

3. High returns come with higher risk. While risk may not be apparent for years, at some point when everyone is relaxed it turns up with a vengeance. Backward-looking measures of volatility are no better than attempting to drive while looking at the rear-view mirror.

4. Be sceptical of financial engineering or hard-to-understand products. The biggest losses for investors in the GFC were generally in products that relied heavily on financial alchemy purporting to turn junk into AAA investments that no one understood.

5. Avoid too much gearing of the wrong sort. Gearing is fine when all is well, but it magnifies losses when things reverse and can force the closure of positions at a loss. When lenders lose their confidence and refuse to roll over maturing debt or when a margin call occurs, investors are forced to sell when they should be buying.

6. The importance of true diversification. While listed property trusts and hedge funds were popular alternatives to low-yielding government bonds prior to the GFC, through the crisis they ran into big trouble (in fact Australian Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) fell 79%), whereas government bonds were the star performers. In a crisis, correlations go to one except for true safe havens.

7. The importance of asset allocation. What matters most for your investments is your asset mix – shares, bonds, cash, property, etc. Exposure to particular shares or fund managers is a second order risk.

Dr Shane Oliver is Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist at AMP Capital, a sponsor of Cuffelinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

For more articles and papers from AMP Capital, please click here.