We spend a significant amount of time explaining to investors our process for entering and exiting investments, which we call 'technical research'. This process occurs after a stock has met our fundamental criteria and it gives us a framework on how best to enter and exit a position. Technical research is based largely on the ‘psychology of the market’ or the ‘psychology of a particular stock’. The process is designed to eliminate as much emotion as possible from the investment process.

Scaling into a position

Our previous article for Cuffelinks Cheap stocks: how to find them and how to buy them explained how we purchase a stock that we think is fundamentally cheap. We commence by adding a 1% position (1% of our portfolio value) only after a stock has finished falling and is rising in price.

There is a lot of emotion and psychology contained even in this initial 1% purchase. If this stock is fundamentally cheap, how did it become cheap? Market participants must have been selling it, but why would they be selling a fundamentally cheap stock? Why did some stocks during the GFC halve in value despite earnings actually going up? Was it based on fundamentals or psychology or, the most important of the emotions, fear? Notably, any initial position is only a 1% position: we are not ‘betting the farm’ and if we are wrong we simply sell the position and take a small loss. This means that each investment decision is not a life and death decision but merely part of an established process.

We do not add to an initial 1% position unless the stock price is going up. We add to our positions in 1% increments and never add to the position if it falls in price.

More often than not potential investors who pride themselves on being deeply fundamental investors challenge this approach. A common question is: if you liked it at $1, don’t you like it more at $0.90? Actually no, we have already lost over 10% on the first position and do not want to ‘throw good money after bad’. What if the fundamentals we have evaluated are wrong, then we would simply be adding to the size of a position that is already going against us. Another common emotional state is that ‘you never go broke taking a profit’, so instead of adding another 1% to a position that has gone up in value why not just sell the first 1% for a profit? The answer is that whilst you cannot go broke making a 5% or 10% profit on a 1% position, you will never make much either. You will not be around to benefit if the stock doubles, triples, quadruples or goes up ten-fold (what Peter Lynch calls ‘ten-baggers’ in his book ‘One Up on Wall Street’).

We add an additional 1% to positions as a stock increases in price up to a maximum of 5% exposure (at cost). In this way we accumulate a 5% position which is a ‘winning’ position i.e. we could only have accumulated a 5% position if the initial position was purchased at lower prices. In this way we add to our winning positions and become more relaxed as our profit in the position grows.

Some investors prefer to take an initial 1% position at say $1 but will then add to the position if it falls to say, 90 cents and then add to it again at say, 80 cents. What an emotional roller coaster it must be. You have made an investment, you add to a losing position, now you are losing twice as much money on the same position and the best solution you can come up with is to add further to a losing position. Now you have a 3% position losing even more money, and where does this logic end? How often can you add to a losing position and how much pain can you bear? Once you have added to a losing position several times, how well equipped are you emotionally to admit you have made a mistake, and at what cost?

Why do share prices overreact?

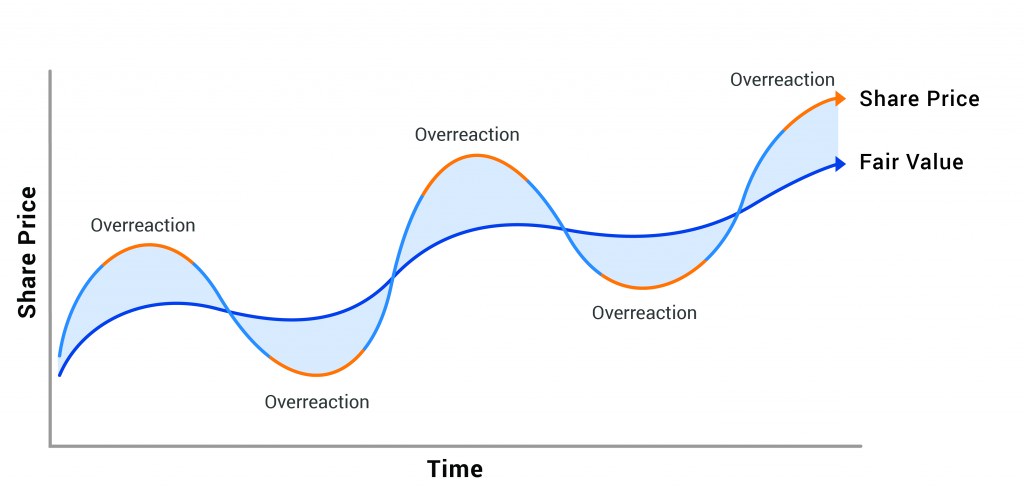

We regularly see the huge role psychology plays in investment. We believe an investor’s fundamental investment process has to be adapted to take account of psychology, including a disciplined approach to entering and exiting fundamental positions. Diagram 1 shows share price overreactions where stocks move well beyond their ‘fundamental value’.

Why does this happen? In ‘Reminiscences of a Stock Operator’, Jesse Livermore gives three main reasons: hope, fear and greed! These three emotions affect the psychology of the market or a particular stock. We experience these emotions despite what the fundamentals are saying.

Remember the point at which you need to rely on your fundamentals is the same point when you start to doubt them. (It is important to note at this stage that the phrase ‘fundamental analysis’ is generally incorrectly used. These so called ‘fundamentals’ are in fact future earnings estimates for a particular company, which are at best informed guesses and at worst pure ‘pie in the sky’ fabrications.) We start to doubt our future earnings estimates (i.e. act emotionally) at the very moment we need to rely on them.

Generally speaking stock prices tend to move up on good news and earnings growth and down on poor news and poor earnings growth. As outlined above, these moves tend to ‘overshoot’ in each direction.

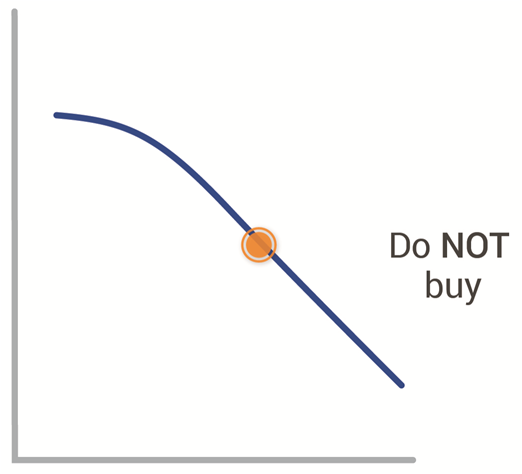

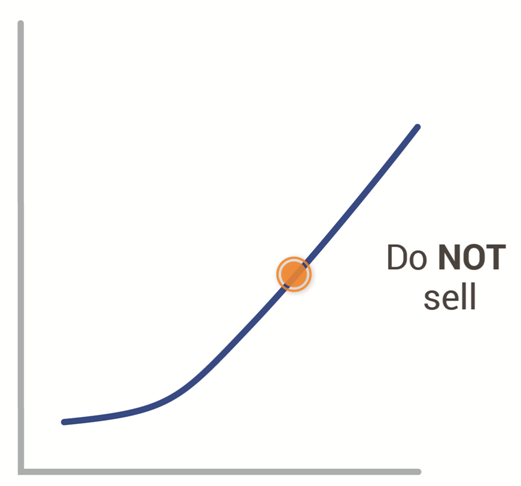

The diagrams below illustrate two basic rules that prevent an investor making common emotional mistakes in an over-reacting market.

Rule Number 1: Do not buy a falling stock

Why are investors attracted to buying falling stocks? Emotions. If it was cheap at higher prices it must be cheaper now. Pick the bottom and look like a hero. Fear of missing out on getting the lowest price and paying more if the price goes back up.

Rule Number 2: Do not sell a rising stock

Again why would someone sell a rising stock? Emotions. The stock has doubled so it must be expensive, and fear that the stock will fall again. Locking in a profit after a doubling of a price feels safe. The desire to ‘lock in a profit’ and ‘be safe’ is potentially one of the biggest investment mistakes we can make.

You would think these two simple rules would be easy to follow, but all the emotions tied up when trying to follow these rules prevent most people from doing so.

Don’t ignore market emotions

Ignoring the psychology of the market is like investing in a bubble. Each investor should realise that with every buy and sell decision, they are bringing to the table a number of powerful and potentially destructive emotions. Good investors should recognise these emotions when they are experiencing them and have processes to deal with them.

Karl Siegling is the Managing Director of Cadence Capital, see www.cadencecapital.com.au. This article is for general education purposes only and does not consider the personal circumstances of any investor.