The tug of war between the real economy and financial economy in the economic Olympics saw the financial economy comfortably take gold. In one camp you have businesses pressured either by a Chinese economy seeking to export its way out of a weak domestic demand problem, or by a domestic economy with housing starts at historic lows relative to population. These sit alongside financial economy businesses buoyed by immigration and asset price bubbles.

Tensions are unevenly spread, and governments everywhere are short of ideas outside government spending and money printing. The quantity of money continues to expand at a rate beyond which the economy can feasibly create businesses to absorb it. And as this money remains dominantly in the hands of individuals, companies and superannuation funds without a need to spend it, asset prices continue to rise.

Economic sustainability continues to play a backseat role. As Javier Milei, the Argentinian President put it, “If printing money would end poverty, printing diplomas would end stupidity”. It remains remarkable that many still believe interest rates and money create a magic elixir to ‘grow’ the economy and ‘create’ wealth when it should be obvious, they can do nothing more than shift wealth around.

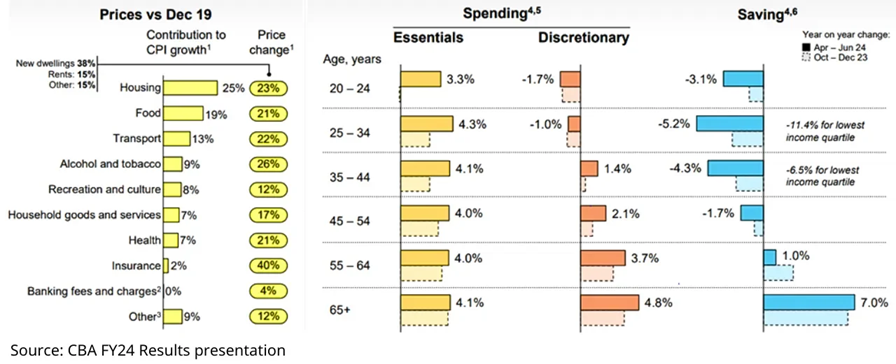

As part of their voluminous results presentation package, CBA provided their usual excellent insights into what’s really happening in the economy through analysing their customer spending data. The most recent update showed exacerbation of the same ongoing trends; older demographics have increased saving without needing to curb spending at all, whilst younger demographics have been footing the bill.

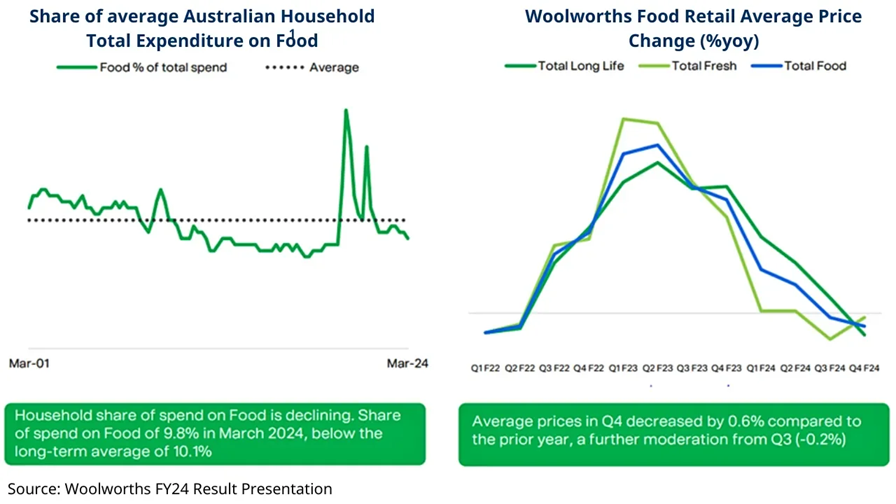

Housing remains the major villain when it comes to both CPI contribution and wealth inequality. While Coles and Woolworths results and commentary indicate the food inflation issues are now largely behind us, housing isn’t.

In this light, a few other trends which CBA highlighted were interesting.

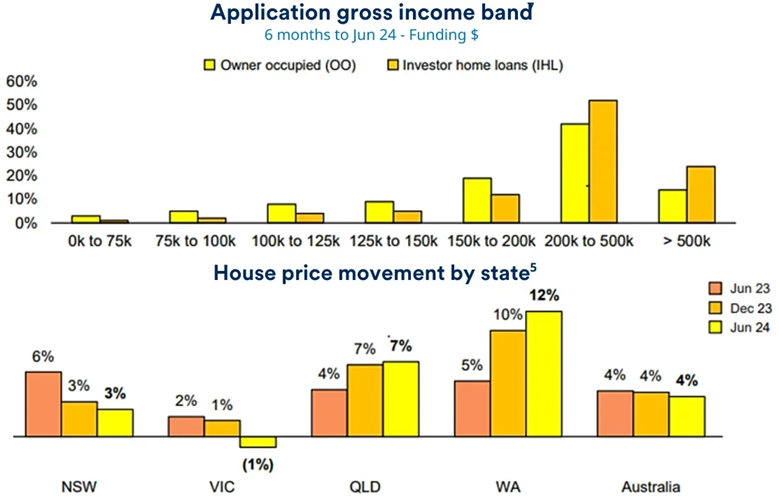

As very high levels of immigration and a raft of other policies providing artificial support to house prices and demand coincided with some of the lowest levels of supply addition in many years, house prices have remained supported despite appalling affordability.

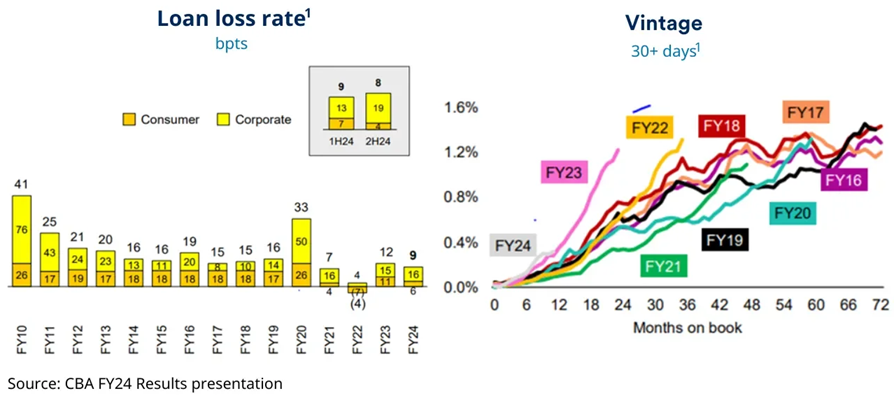

Positive house price movements have meant almost no consumer loan losses. More interestingly, despite most incremental loans being made to borrowers with very high levels of gross income, arrears are climbing. Seeing arrears levels climb quickly on loans only made in the last 1-2 years suggest finding creditworthy borrowers in Australia remains challenging. This contributes to our view that only very low levels of private sector credit growth look sustainable given the starting point.

As China continues to grapple with the aftermath of funnelling vastly too much credit towards property over an extended period, it remains difficult to understand why so many believe the same economic principles don’t apply here. On the positive side, corporate lending losses remain incredibly benign.

CBA has erudite and capable leadership. But we remain perplexed as to why an earnings yield of not much more than 4% and market capitalisation of around 10% of Australian GDP equates to an appealing investment proposition given a barely flat earnings outlook given limited volume growth, already reasonable net interest margins and still rising costs.

As falling commodity prices and resulting earnings declines see investors desert materials, energy and anything experiencing cyclical decline, it is perhaps not much more complex than flat being better than down.

5

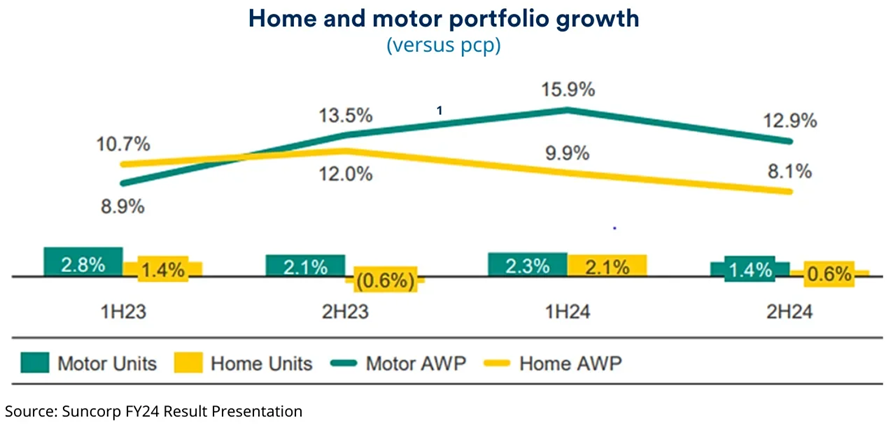

Outside banks, the insurance sector has been the other beneficiary of strongly rising pricing over recent years.

Insurance brokers have sidestepped the regulatory inquiries which have mired the rest of the financial services industry in worthless paperwork and online training courses, and have enjoyed a boom from commission revenues attached to sharply inflating premiums. Meanwhile, the insurers have continued to leak most of the growth in premiums in rising claims costs.

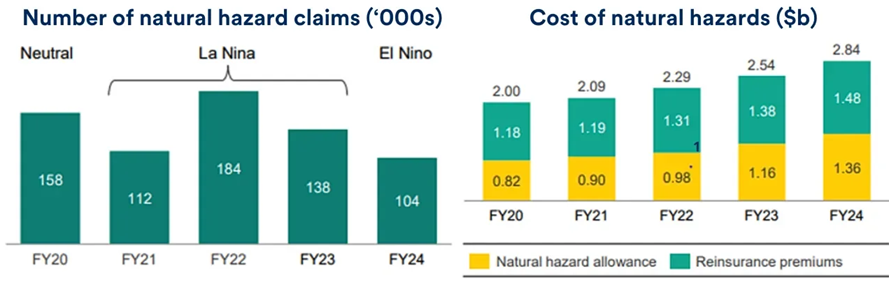

Contrary to popular wisdom, Suncorp data indicates the problems relate almost solely to increasing costs per claim rather than claim numbers. Blaming climate change for rising costs might be convenient, however, it is not supported by the data. Flexible plumbing pipes (shorter lives and greater failure rates), lower quality workmanship, fire risk from lithium batteries and building on flood plains are amongst the myriad of factors exaggerating the ballooning costs of labour and regulation, highlighting again the hidden costs of sacrificing the long-term for the short-term.

In the same vein, as sales of electric vehicles hit a few speed bumps, insurance costs (courtesy of higher repair costs and greater write-offs) and poor resale values are emerging as reasons why the total cost of ownership for EV’s is far less persuasive (i.e. higher) than proponents would hope.

Along with headaches on shouldering the costs of charging and electricity transmission infrastructure, which is also becoming a barrier for data centre development, there is a long line of businesses with a preference for socialising the high costs of infrastructure on which their ‘capital light’ business piggyback. It is not easy to disembark the subsidy train and this train has an increasing number of passengers.

The gold medallist in the ‘capital light’ love affair remains the technology sector, where investors continue to pile on astonishing large amounts of market value for astonishingly small earnings surprises. Meanwhile, much of the rest of the economy struggles to determine where their efficiency gains have gone as they digest yet another massive price increase from Microsoft or AWS, and put through a few more ‘one-off’ charges for a new ERP system or transitioning to the cloud.

Companies delivering earnings gains of vastly greater quantum saw nothing like the same dollar increments in valuation. The machines which increasingly dominate equity market price setting might create the ridiculous reactions to incremental information. Yet we remain amazed at the extent to which supposed fundamental investors can happily multiply earnings by whatever random number is necessary to justify copying this behaviour.

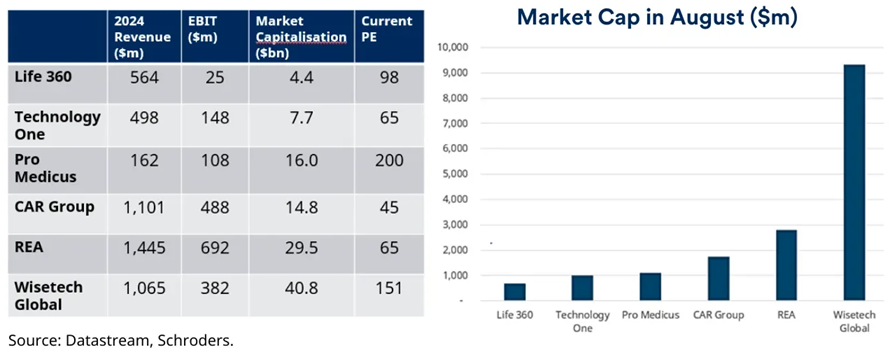

Wisetech Global (+25.1%) was probably the poster child for this behaviour during August.

Revenue growth of a little over $200 million (aided by acquisitions) saw EBIT growth of around $80 million aided by R&D capitalisation rising by $60 million. Nevertheless, guidance for rising EBITDA margins (up from 48% to 51-52%), was sufficient to whip investors into a frenzy, adding more than $9 billion in market value. Just the August share price increment was more than 24 times the total EBIT of the business in 2024. Crazy times indeed.

On the real economy side of the equation, life was more uncomfortable. While businesses such as Brambles, Telstra and Seven Group delivered strong results driven by efficiency gains and an ability to pass on higher costs to customers, those without this insulation suffered.

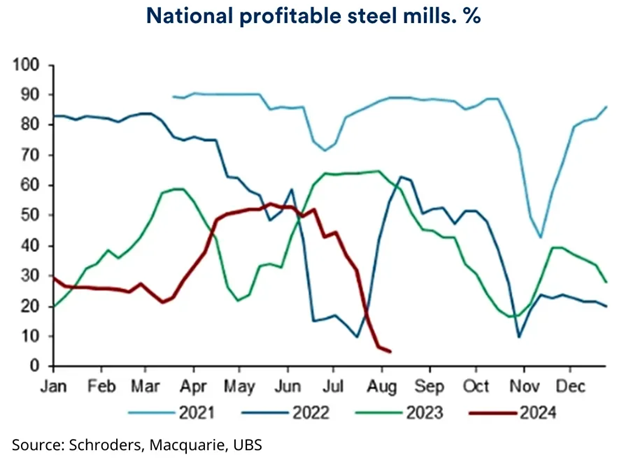

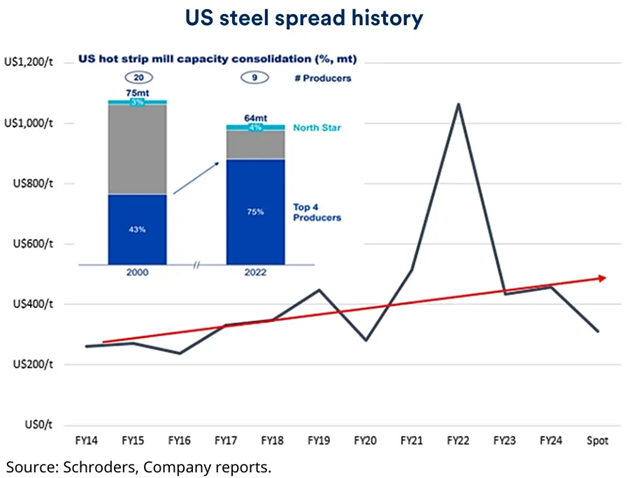

Generally falling commodity prices are impacting all resource producers, whilst the impact of China’s increasing reliance on exports to drive growth despite abysmal profitability, is seeing price pressure transmitted globally. Steel markets are a major case in point. Despite successful strategies to build end market brands, highly capable companies such as Bluescope Steel are seeing margins crunched as Chinese steel exports near 100m tonnes, far in excess of the ability of rest of world demand to digest.

While all economic logic suggests loss making mills should eventually close, supply reduce (along with iron demand) and margins rebound through a combination of lower iron ore and/or higher steel prices, the time frame for logic to prevail is often longer than expected. We’ve seen this movie before. A healthy balance sheet and strong cost position means Bluescope remains well positioned to enjoy the inevitable improvement, and its through the cycle returns remain impressive.

In an investment landscape in which the incremental piece of information is the holy grail, while the starting point of being incredibly cheap or incredibly expensive means little, our inclination for patience and a focus on the long-term may be tantamount to shouting at the rain; we’ll yell anyway.

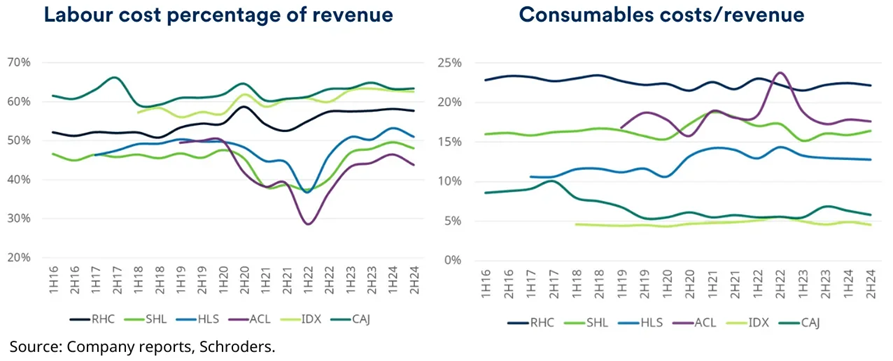

Of the many other more pedestrian results, a few themes were consistent. Large labour forces experiencing significant wage inflation and government or powerful payers disinclined to allow revenue to compensate for this cost inflation featured prominently.

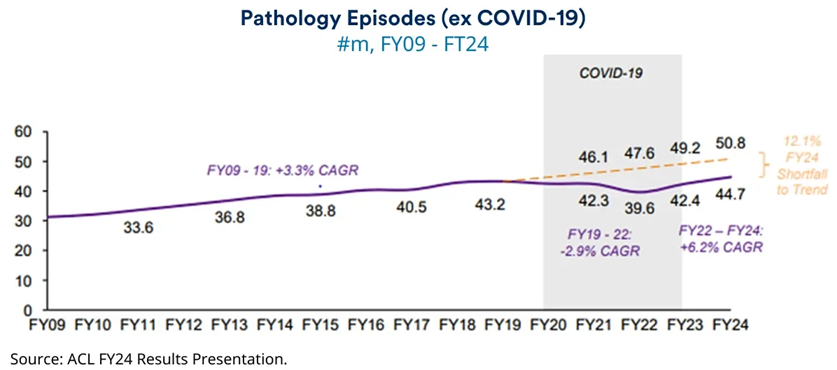

Healthcare services companies such as Ramsay Healthcare, Sonic Healthcare, Healius, Capital Health, Integral Diagnostics and Australian Clinical Labs have all been in this camp over recent years. More drawn out recovery from COVID interruptions together with capacity addition, which has perhaps failed to adapt to trends towards day surgery and out of hospital care, means capacity utilisation remains challenged.

Pathology episodes are only just recovering to pre COVID levels. Cost processes more attuned to dealing with stable and growing demand have also struggled to deal efficiently with volatility. Gradual margin decline and erosion in return on capital has been the order of the day. Excessive gearing accumulated through years of growing size, rather than underlying profitability, has added to the pain as interest rates have risen. Reasons for pessimism abound.

We’d approach from a more positive standpoint. Management teams channelling Kevin Costner in Field of Dreams; “Build it and they will come”, are increasingly meeting capital providers more inclined towards ‘don’t build it or you’ll be gone’. Weak players in a challenged industry are likely to disappear and the threat of public hospitals being overwhelmed by demand may begin to force the government’s hand.

Stand offs between hospitals and PHI’s (Private Health Insurers) may well grow. As crucial services with substantially growing demand and (in the case of pathology and radiology) massive payoffs in quality of life and healthcare savings, together with significant potential gains through technology and AI, the scope for sentiment, valuations and profitability to expand as pessimism subsides is substantial.

Outlook

Many, including us, have been surprised at the resilience of equity markets to the interest rate rises which would normally prove a headwind.

It is clear interest rates are not inducing the same reactions as past cycles. Interestingly, given the much larger size of asset markets relative to the economy, the role interest rates have played in diverting more wealth towards the elderly and wealthy demographics with the propensity to save and invest rather than spend, and away from the demographics more likely to spend than invest, the potential for falling interest rates to impart the reverse impact seems somewhat logical.

As spending power is put back in the hands of those currently struggling, hopefully providing a boost to the real economy, the expectations that falling interest rates provide yet more impetus for equity markets may yet be challenged. The chorus of commentators determined to hit the ‘nail’ of inflation with the ‘hammer’ of interest rates, suggests there is not much nuance in the conversation.

Why interest rates are the best tool to quell inflation stemming from government spending, constrained housing supply, uncontrolled housing demand and high immigration levels remains a challenging one from our perspective.

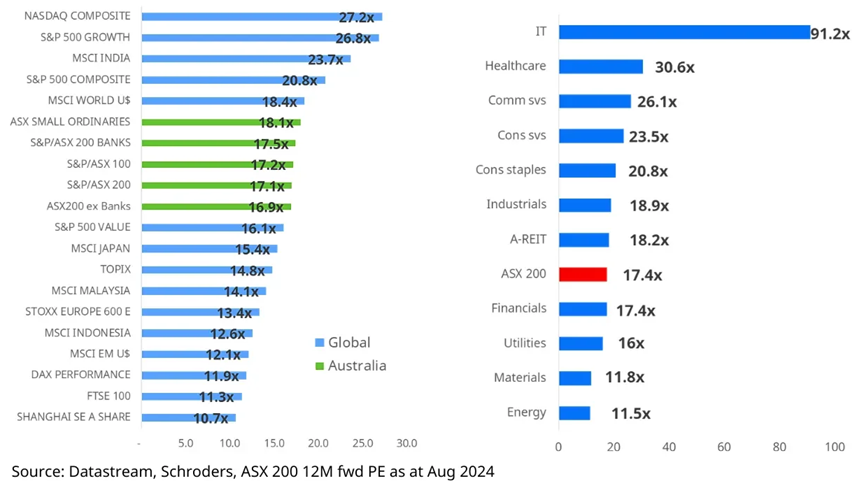

The allure of growth remains as appealing and as highly valued as almost any time in history. At an overall market level, where growth is perceived (US technology, India) multiples know almost no bounds, while the mundane and challenged (Europe, China) remain friendless. Within the domestic equity market, where we have expected extreme bifurcation to close, it has only grown.

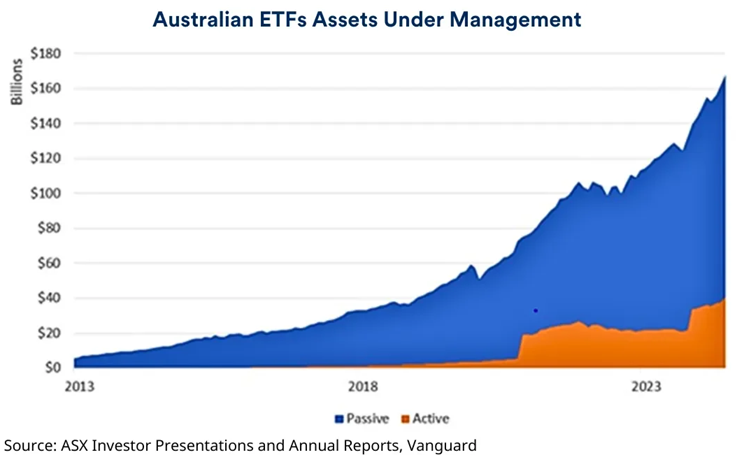

While volatility creates the perception of increasing risk, we would beg to differ. Financial leverage at the company level is not increasing and most companies have coped well with the challenges of volatile demand brought on by COVID and rising interest rates. As we have mentioned previously, volatility is a symptom of less trading volume setting the price on more market capitalisation. As the ASX statistics below show, cash market trading value has barely moved whilst market value has doubled. Passive free riders continue to grow.

We remain of the (somewhat unpopular) view that risk escalates as the price paid for future cashflows escalates. Money is papering over a lot of cracks while buying reality is getting cheaper.

Martin Conlon is Head of Australian Equities at Schroders, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article does not contain and should not be taken as containing any financial product advice or financial product recommendations. It does not take into consideration your personal objectives, financial situation or needs.

For more articles and papers from Schroders, click here.