One of the bigger challenges facing investors is to hang on to their shares during a market selloff, or when the perception that the future for equities is bleak. Investors often justify the sale by telling themselves they will ‘buy back at a lower price’, but that will probably become a doomed attempt to make two correct timing decisions. It may mean the investor is out of the market and misses long-term gains.

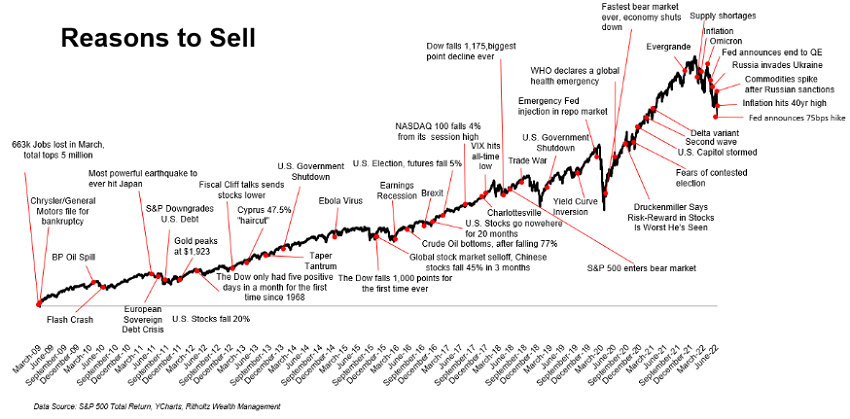

The sharemarket falls by 10% or more at some stage in most years and suffers negative returns in about three out of every 10 years. Substantial falls of over 30% occur every 20 years or so. There is never a shortage of reasons to sell, as shown below, and always an expert fund manager warning of doom. For retirees in particular, the threat of a significant loss of capital can be too much to bear, leading to selling even when shares are supposed to be part of a long-term portfolio holding.

Click to enlarge

Double trouble, both the sale and the repurchase decision

The right time to sell is difficult enough to time, and generally done at the wrong moment. Deciding to sell and then buy when the market might be somehow lower is even tougher, doubling the required timing luck. As Howard Marks said:

"In both economic forecasting and investment management, it’s worth noting that there’s usually someone who gets it exactly right … but it’s rarely the same person twice."

Those who are reassured by the intention to buy back in as soon as things have ‘settled down’ face two major hurdles:

- If the market falls, the temptation is to wait longer for the bottom, as if someone rings a bell on the critical day. OR

- If the market rises, there is a psychological hurdle of paying more for the same shares that were recently sold at a lower price.

At least the decision to sell may be justified and driven supposedly by short-term risk mitigation, or a market event or changed outlook which justified caution. But what trigger does the investor look for to buy back in?

The impact of major falls such as in the GFC

The GFC was about 15 years ago but its impact has remained profound for many investors. Between November 2007 and March 2009, the S&P/ASX200 Accumulation Index fell 51%, and it was a shock for many.

The most unfortunate impact was that retirees experienced such a rapid loss in the value of their retirement savings that it turned them against equity investing. They not only missed the subsequent recovery but the large fall drove a conservatism that misses the long-term benefits of equity market growth.

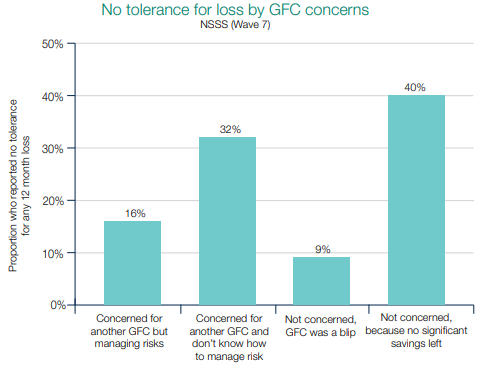

The most comprehensive survey of the reactions of older Australians to the GFC was conducted by National Seniors. Although Once Bitten Twice Shy was published five years ago in 2018, it shows the ongoing impact of a significant market fall. The survey concluded:

“Ten years on from the GFC, its impact lingers for most older Australians, who express a ‘once bitten twice shy’ sentiment as a result of their experiences. Seven out of 10 are still concerned about another potential market collapse. Older Australians are still wary of market turmoil, with only one in fourteen thought they would be able to tolerate a loss of 20% or higher – about the same as the fall in superannuation returns during the GFC a decade ago. One in four said they could tolerate losses greater than 10%, though the same proportion said they could not tolerate any annual loss on their portfolio.”

Relationship between having no tolerance for loss and GFC concerns (%)

Long-term consequences for investment returns

There are many studies which show that investors earn less than the funds they invest in. For example, Morningstar produces an annual Mind the Gap report, which concludes in 2023:

“Our annual study of dollar-weighted returns (also known as investor returns) finds investors earned about 6% per year on the average dollar they invested in mutual funds and exchange-traded funds over the trailing 10 years ended 31 December 2022. This is about 1.7% less than the total returns their fund investments generated over the same period. This shortfall, or gap, stems from poorly timed purchases and sales of fund shares, which cost investors roughly one fifth the return they would have earned if they had simply bought and held.”

Morningstar Australia’s Mark LaMonica examined the history of the report and the numbers have been similar for many years. He says:

“The larger point is that timing the market is hard. Expectations are baked into prices which means that once there is more clarity on the certainty of an outcome it is often too late. Timing the market means anticipating future events before other investors. It also means getting the call right. That can be a lonely and intellectually challenging exercise. Because everyone else is doing and saying the opposite. It is hard to go against the crowd.”

My missed reinvestment after a ‘forced’ sale

For many years, when presenting to audiences on investing and superannuation, I focussed my material on portfolio construction, asset allocation and long-term planning. I am not a stock analyst and I argued that returns will be driven more by allocations between various asset classes than particular stocks over the long run. I might discuss managed funds versus ETFs but not Rio versus BHP or Westpac versus CBA.

Despite this background, I am invariably asked for my stock picks. People love stock stories, and to show I am not clueless on particular companies, I explain that I spend most waking hours in some interaction with the products of three great US companies – Microsoft, Apple and Google (Alphabet). I like funds which hold these stocks or I invest directly.

For example, it would be impossible for me not to renew my subscription with Microsoft. I am highly price insensitive, and when this email came in recently, I did not even compare it with the previous year, but I have no doubt it is a higher cost:

“Your subscription is scheduled to be automatically renewed. On Saturday, August 19, 2023, AUD 139.00 including taxes will be charged to XXX.”

And of course, Microsoft has other great businesses (cloud and server, LinkedIn, hardware, gaming, etc).

Similarly, I use my mobile phone dozens of times a day. A few years ago, I switched cost from Apple to Samsung because I wanted a phone with a pen to jot down ideas. Apple does not produce such a phone. But for overall functionality, I found Samsung was not as smooth and well sorted, and after a few years, I switched back to Apple, despite the new iPhone costing $1,400. Apple raises its prices every year and still sells hundreds of millions of its phones and a billion people are integrated into its services.

And Google is so much part of our lives that it is a verb, my personal email is Gmail, I watch a lot of YouTube and use maps and Chrome.

So I tell my audiences that I think there is a strong case to include these great companies in most portfolios, perhaps subject to valuation, and I intend to hold them for a long time.

But I didn’t.

For reasons of administrative simplicity, I invested directly in these US companies using the Deutsche and Chi-X (now Cboe) product called TraCRs, as well as via some growth-oriented funds. It allowed easy investment in many leading US companies on the ASX, handling the FX and any other requirements, as if buying an Australian company. Then in November 2021, Deutsche announced it was terminating the product from 21 February 2022. Investors were given the choice to sell, convert to the underlying US shares by opening a new brokerage account, or do nothing and Deutsche would arrange the sale. I decided to sell the TraCRs on market (completed between 17 and 21 February 2022) but I opened a new international brokerage account with the intention of buying the shares directly.

But I didn’t.

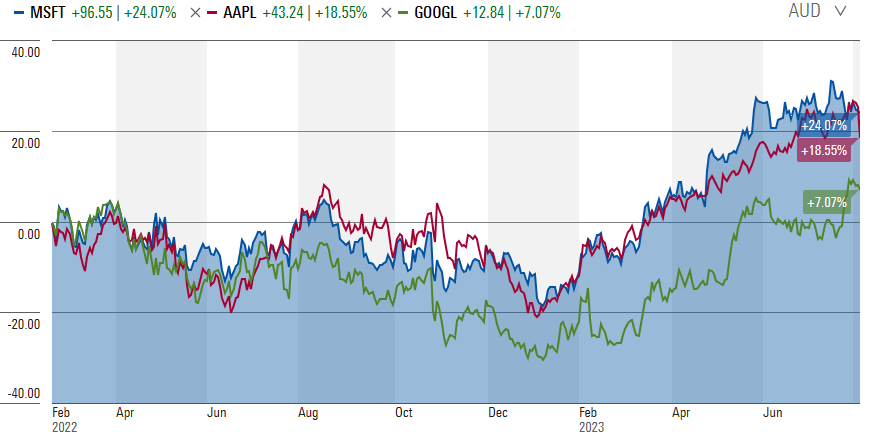

For much of 2022, I looked like a timing genius. Although I wanted to hold these great companies, they all fell in price over 2022 as interest rates rose, investors thought they were overvalued, and the recession threat loomed.

Then along came AI and each of them has boomed in 2023. My plan to reinvest was missed. While I can defend myself by claiming I was pushed to sell, I could have bought back immediately, but I took a stab at market timing.

The chart from Morningstar below shows that since I sold my TraCRs in February 2022, in AUD terms, Microsoft is up 24.1%, Apple is up 18.6% and Alphabet is up 7.1%. They fell heavily over 2022 but have come back with a surge, and I don’t own any of them, other than through managed funds and ETFs. I did not anticipate the AI boom and I expected interest rate rises to bite harder, in a failed attempt to time the reinvestment price.

What’s the main lesson?

Although this example relates to a few specific companies, the main lesson relates to exposure to equity markets overall. Perhaps timing of the exit will look good for a while, but the reinvestment might be missed, and with it the long-term exposure.

If you have identified a great company, let the vicissitudes of the markets and months roll past and the years and decades will look after themselves. Correct execution of two timing decisions will be more a matter of luck than profound foresight.

Graham Hand is Editor-At-Large at Firstlinks. This article is general information and not investment advice.