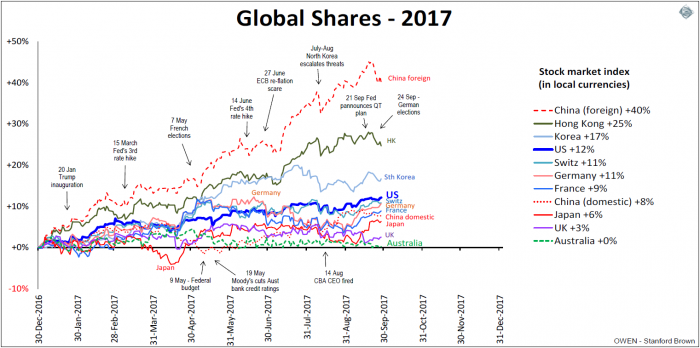

The 2017 calendar year has been reasonably good for shares around the world. Nearly all stock markets are posting gains against the headwinds of rising protectionism, monetary tightening, political fragmentation and military tensions.

Australia is crawling along at the bottom of the pack despite enjoying the highest economic growth rate in the developed world and strong rises in company earnings and dividends. The problem is that most of the increases in profits and dividends are merely making up for losses and dividend cuts last year caused by the 2014-15 commodities collapse. The turnarounds in profits and dividends this year were driven by the commodities rebound from China’s stimulus in 2016, which was pure luck and totally out of our control. This rebound has flattened and will be reflected in next year’s results. An economy in which company and tax revenues are at the mercy of commodities prices set by foreigners, and which runs chronic current account deficits because it spends more than it earns and so is always reliant on foreign capital, is called a ‘banana republic’.

Low allocations to global shares has punished portfolios

The US has been the strongest of the developed markets, despite two further rate hikes this year and more on the way. A positive has been the 8% decline in the US dollar as the early Trump euphoria has worn off. On 21 September the Fed announced its long-awaited plans for ‘QT’ (quantitative tightening) to replace ‘QE’ (quantitative easing), where the Fed will reduce its $4.5 trillion pile of bonds it bought after the GFC to depress interest rates and the US dollar, and to lift asset prices.

European shares have also done reasonably well given sluggish growth and rising political and social tensions. European confidence was boosted early in the year by Dutch PM Mark Rutte’s win in the Dutch elections on 14 March, followed by Emmanuel Macron’s win in the French elections on 7 May. These early hopes were dashed by Angela Merkel’s poor showing in the German elections on 24 September which saw the dramatic rise of the anti-EU and anti-immigration AfD Party.

Click to enlarge

Japanese shares are also up modestly this year, led by Keyence (IT), Sony and Softbank. The economy is finally showing signs of life but the resultant strong yen is hampering exports and share prices. PM Shinzo Abe has grabbed the opportunity for another early election to try to rebuild his support in the face of the rising military threat from North Korea and China. Three terms of ‘Abenomics’ have done little for economic growth and inflation, but they have certainly boosted share prices.

Chinese domestic shares (those traded inside China by locals) have edged higher this year. Whereas 2016 was a year of stimulus spending and easy money, 2017 has been a year of rate hikes and regulatory curbs to slow the housing boom and to stem capital outflows. On the other hand, Chinese foreign shares (traded mainly in New York) have been the stars. The glamour tech stocks like Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu and many others are all up between 50% and 100% so far this year. The boom in Chinese tech stocks is reminiscent of the 1990s US ‘dot com’ boom.

Are shares long-term ‘safe havens’?

Recently I have been receiving an increasing number of enquiries asking whether investors should get out of the share market because shares are seen as ‘scary’ and ‘risky’ and instead put their money into ‘safe havens’ – in particular gold, bank deposits or government bonds. If you read the media headlines it seems that share prices are ultra-high, property prices are about to crash, inflation is about to take off, and now we are heading for another global war!

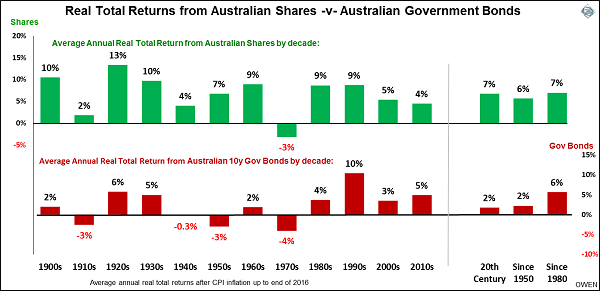

The problem is that even if all of these things were true (which they are probably not), broad diversified share investments are better for long term investors than the so-called ‘safe havens’. Australian shares as a whole have delivered not only higher average returns than the ‘safe haven’ assets but they have been more consistent and reliable for long-term investors. Shares have experienced fewer periods of negative returns, higher (or ‘less bad’) negative returns, and shorter times to recover their real value after downturns.

We are not talking about daily returns and daily volatility here – nor even monthly or yearly ups and downs. That’s for day traders and short-term punters to worry about. Long-term investors should look through the short term ‘noise’ in the media headlines to understand how markets work over the long term. Even for retired couples in their 60s or 70s, one of them is likely to live to 100, so that’s a 30- or 40-year investment horizon.

The chart below shows long-term real returns (after inflation) from Australian shares versus government bonds for each decade since 1900. (We will look at gold and bank deposits next week). The right of the chart shows average returns for the 20th century, returns since 1950, and since 1980.

Diversified Australian shares have generated consistently higher average returns than bonds and have suffered only one decade of negative real returns, in the high inflation 1970s.

Government bonds provided hardly any protection against neither shares nor inflation. Nor were they a store of wealth, with four decade-long periods of negative real returns. They generated low average returns over the whole period, at about 5% per year lower than shares, and four times as many decades of real losses than from shares. In the only decade when shares when backwards - the 1970s - government bonds did even worse.

Briefly, what lies ahead?

Notwithstanding the long-term benefits of shares, there are plenty of risks to local and global markets. The widely-feared global ‘reflation’ scare - which raised bond yields and the US dollar late last year and immediately following the Trump election - has faded. The US dollar and bond yields have subsided as optimism faded. We believe there are more risks in global slowdowns than in runaway inflation.

The US has gone from Trump euphoria to Trump policy stagnation. Economic activity and jobs growth have picked up this year but is likely to slow again if Trump fails to achieve the big stimulatory actions of tax cuts and infrastructure spending. If passed, the tax package will probably be favourable, in particular the reductions in taxes on companies and on foreign profits, and measures to repatriate the $3 trillion of cash from past profits of American companies. Working against this will be Trump’s rising list of trade protection measures.

Europe is seeing a continuing trend away from integration toward nationalism, as witnessed by the rise of the right wing in the German elections. Europe needs young immigrants to work and pay taxes to fund the rapidly-growing rump of retirees. Immigration has always been the driver of economic growth but xenophobia and racism are more powerful forces.

Global tightening of monetary policy should ordinarily be seen as a good sign that economies are strong enough to allow rate rises. This is the case in the US and China. But in Europe and Japan, where there is early talk of scaling back QE asset buying and negative/zero interest rates, it is because central banks and governments have simply run out of ideas on how to stimulate growth, employment and price inflation. They have finally realised that ‘QE’ and negative interest rates have done little more than distort markets and artificially inflate asset prices.

The best chance for a rapid revival of price inflation is war or a rapid military build-up. Trump and Kim Jong-un are doing their bit to move that along.

(Next week, we will examine whether bank term deposits or gold are good safe haven investments).

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at privately-owned advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is general information that does not consider the circumstances of any individual. Investors should seek professional advice before acting on any of these comments.