The recent return of inflation has spurred a sudden surge in interest in the implications for investors. In reality, inflation has always been a destroyer of the spending power of money, and therefore of critical importance for investors, even in the so-called ‘low inflation’ years.

Don't underestimate the impact of inflation

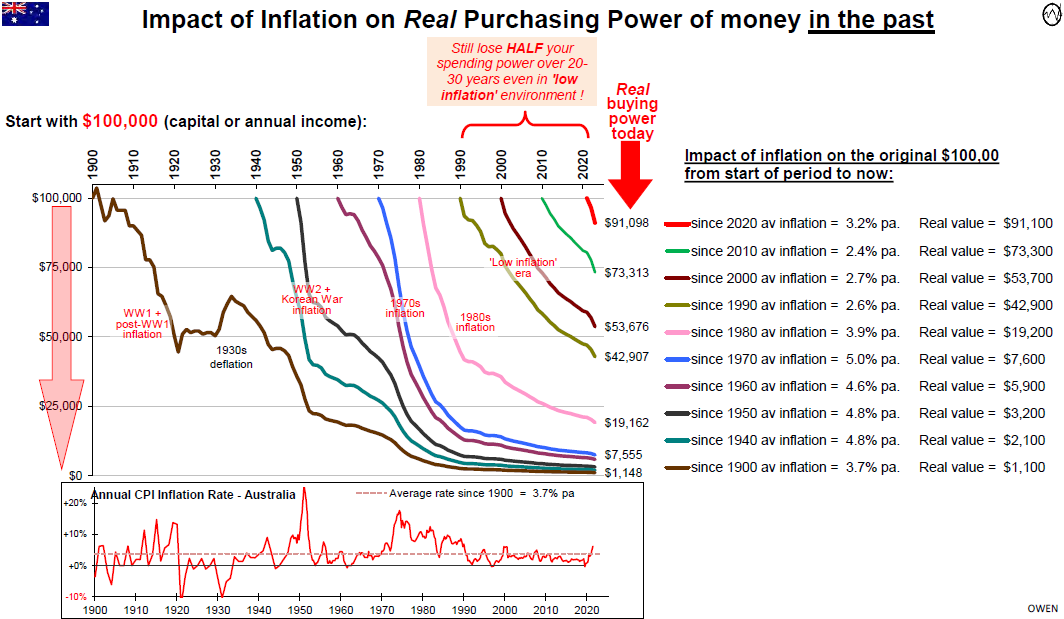

The chart below shows the impact of inflation on $100,000 in assets or income over time in Australia, from different starting points. For example, $100,000 of assets or income in 1980 was a lot of money at that time (the median Sydney house price was just $69,000 in 1980) but $100,000 in 1980 dollars would have been whittled down to just $19,000 in today’s dollars if you didn’t protect it against inflation.

Another way of looking at it is if you had $100,000 in cash in 1980 and locked it in a safe then opened the safe today, you still have that same $100,000 but it would only buy $19,000 worth of today’s goods and services. (Or if you invested in term deposits in 1980 and you lived off the interest). Inflation over the years has eaten away 81% of its purchasing power.

The 1980 ‘real’ (i.e., after inflation) value line is the pink line starting from 1980 near the middle of the chart. We can see that the real purchasing power of $100,000 in 1980 decayed very quickly in the high inflation 1980s, but then the rate of value decay eased off (a less steep downward value decay curve) in recent decades. The section at the bottom of the chart shows the annual CPI inflation rate in Australia since 1990. Inflation was very high in the 1970s, then declined in the 1980s, and has been relatively ‘low’ in the 2000s and 2010s decades.

The problem is that, even in these so-called ‘low inflation’ years, inflation still had a serious detrimental impact on wealth and incomes. For example:

- $100,000 starting in 1990 has been eaten away to a purchasing power of just $43,000 today.

- $100,000 starting in 2000 has been eaten away to a purchasing power of just $54,000 today.

- Even in the ultra-low inflation post-GFC years, $100,000 in 2010 has been eaten away to a purchasing power of just $73,000 today.

- In the past two years alone, $100,000 at the start of 2020 has already lost 9% of its purchasing power to $91,000 today (the steep red value decay curve to the right of the chart).

The wealth-destroying effects of inflation never went away. Remember how central bankers dreamed about reviving inflation in the post-GFC years, and especially in 2020-21. We are all paying for that now!

Planning for future inflation

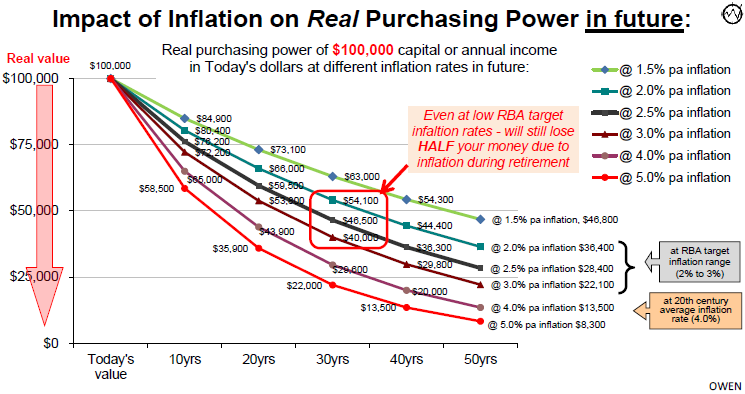

The next chart shows the impact of inflation on the purchasing power of money over time, at different rates of inflation. Obviously the higher the rate of inflation, the greater the destruction of the real purchasing power of money.

Even if inflation can be contained within the RBA’s target range of 2-3% per year, money still loses half of its purchasing power over 30 years (highlighted in the red box) if we don’t invest in assets that at least keep pace with inflation. Even if inflation were contained at a very low 1.5% per annum, you will still lose 37% of purchasing power over 30 years.

The second key lesson from this chart is that the longer we need the money to last, the more of it is eaten away by inflation, and therefore the more important it is to invest in ‘growth’ assets that offer some inflation protection.

In previous generations, time in retirement was relatively short. Most people had working lives of 40 years or more (from their late teens to retirement in their 60s). Retirement was usually only for half a dozen years or so, if that. Inflation, and even high inflation, did not have much time to work its destructive damage on their savings, and most people lived off the age pension, which was indexed to wage inflation.

Now, a large proportion of the population live well into their 90s, or even past 100, and life expectancy is increasing further with advances in medicine and nutrition. Retirement funds need to last several decades, and so the capital values and incomes need to be invested in growth assets to keep pace with inflation for several decades.

The need for growth assets over time

There are many types of assets used in long-term investment portfolios, but they fall into two main groups – ‘growth’ and ‘defensive’ assets.

The main types of growth assets are equity (ownership) interests in businesses (e.g., in the form of shares in listed or unlisted companies), and real estate (residential, commercial offices, retail shops, etc.). Companies (especially of diversified mix) can often offer good inflation hedges, with rising revenues, profits, dividends and capital values. In the case of property, well located and managed properties (especially a diversified mix) can also see their rents and capital values rise with inflation, depending on their location, supply and demand for tenants, etc. The main downside with ‘growth’ assets is that the income (dividends, rent), and also their capital values, can suffer big falls in business/credit cycles, especially in broad economic recessions.

On the other hand, defensive assets are mainly debt funds lent to governments (in the form of treasury bonds, notes and bills), debt funds lent to businesses (corporate bonds, notes), debt funds lent to banks (bank deposits, bills, notes and hybrids), and debt funds lent to property owners and developers (mortgages, debentures).

In essence, with ‘defensive assets’ you are a lender, but with ‘growth assets’ you are a part-owner.

The defensive (debt) assets are usually favourites with retirees because they offer advantages of regular, relatively reliable income, and usually relatively stable capital values. The downside of their relatively stable capital values and income is that capital values (and future income) do not provide any protection against inflation. They suffer the inflation decay illustrated in the above charts. People investing for periods of more than a few years (which includes almost all retirees) still need high quality, diversified ‘growth’ assets in their portfolios.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.