Every six months, I give an update on the valuations of key asset classes and how they compare. Here’s the latest chart on yields for the four major asset classes: cash, bonds, property, and stocks. I’ve included the inflation rate as a point of comparison.

What stands out from the chart is that the inflation rate of 5.4% (this is the September quarter figure rather than the monthly data which are less reliable) is higher than the yield of almost every asset class. That means that most assets are losing money in real terms (real yield is asset yield minus the inflation rate).

Why is that happening? Part of the answer is that markets expect inflation will continue to ease. Inflation in Australia is by far the highest of the top 15 developed economies in the world. It bottomed in negative territory at the start of Covid in 2020 before climbing to 7.8% at the end of last year, then falling to 5.4%.

Australia inflation rate

The new RBA Governor Michelle Bullock has said that inflation here is largely a homegrown problem. I highly doubt that and see it as a way for the RBA to justify being paranoid about inflation and thereby keeping interest rates higher for longer.

The RBA forecasts inflation will ease to 4% by mid-next year and 3% by the end of 2025. In other words, inflation won’t get back to the RBA’s target of 2-3% possibly for another two years.

The inflation picture in the US is more encouraging. Data out this week showed the consumer price index dropped to 3.1%. It could well get back to the Federal Reserve’s target of 2% next year.

If Australian inflation is principally caused by global issues, with a lag, might that mean inflation here could fall faster than expected? That’s entirely possible, though it will also depend on factors including the health of global economies.

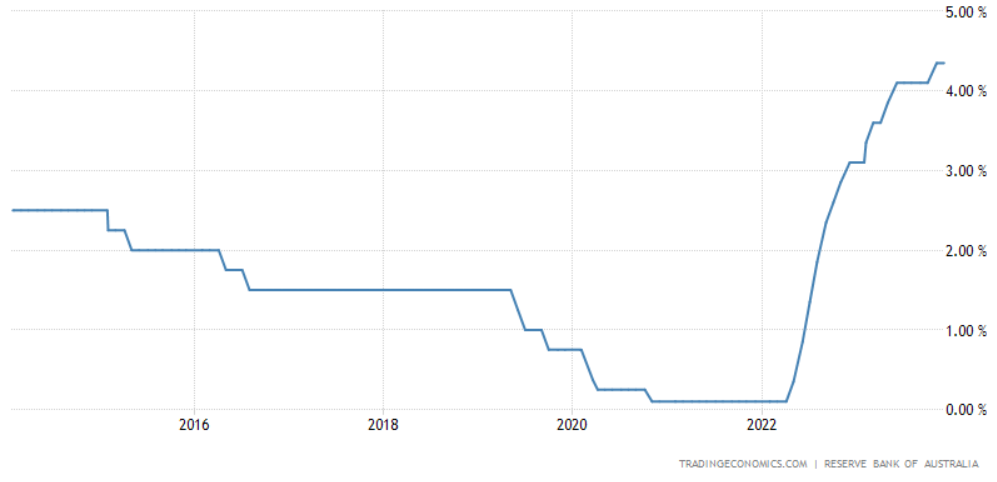

What does that mean for interest rates in Australia? As always, it’s difficult to tell. We’ve gone from a rate of 0.10% in April 2022 to 4.35% now. That hasn’t impacted the economy, especially spending, as much as most expected. Warnings about the so-called ‘mortgage cliff’ haven’t eventuated. That’s not to say that there won’t be an impact on the economy in future, though.

Australia interest rate

What’s clear is that if the RBA’s forecasts of a gradual decline in inflation are correct, then the yields on most assets won’t offer much in the way of real returns over the next 12 months.

Moreover, most asset yields trail the Australian 10-year government bond yield – the risk-free rate - of 4.35%. Ordinarily, assets should be priced at a yield above that rate to reflect the risk of owning them versus the risk-free rate. That’s not happening now, and it means that risk may not correctly priced with these assets.

Cash is back, or is it?

In 2022, stocks and bonds endured one of their worst years for some time. News headlines proclaimed, “the end of the 60/40 portfolio” and the possibility of a long bond bear market. Then in March this year, Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse both collapsed.

All this shook investors. What did they do? Many chose to switch their money out of stocks and bonds and into cash.

In the US, it’s estimated that there’s around $5.6 trillion in money market instruments. Australia has a less developed money market, so people turn instead to bank savings accounts and term deposits.

The move from stocks and bonds into cash, especially in the first half of the year, was understandable. After all, money in the bank had earnt next to nothing for 15 years. Suddenly, it had a decent yield.

Though understandable, holding cash even in term deposits this year has been a losing proposition in real terms. That is, cash has returned less than inflation. Therefore, people invested in cash have lost purchasing power.

The big question is whether cash is attractive for 2024? It really depends on inflation. If inflation heads below 5% as almost everyone expects, then having some money in a 6 to 12-month term deposit with a rate above 5% makes sense. That’s especially if you’re worried about the valuations of stocks and other assets. The risk is that inflation remains high, and cash again loses purchasing power.

Bonds are back, or are they?

Throughout this year, various bond managers have declared that “bonds are back”. That didn’t make sense for much of the year, at least for government bonds, as yields didn’t seem attractive when compared to inflation. By November, as Australia’s 10-year bond yield almost touched 5%, and with inflation pulling back sharply, bonds started to offer better value.

After an extraordinary November, the 10-year yield is back to 4.35%. That’s more than 1% below the current inflation rate. Inflation has to pull back a lot for that yield to become attractive again.

Source: Trading economics

Yes, you can buy other bonds at better yields. Corporate bonds can be purchased with +5.5% yields, and non-investment grade bonds at much higher yields. These other bonds also looked better value a month ago than they do today.

How do bonds compare to cash? At this moment, I think cash offers more value than government bonds. Yet, it’s important to note that the two assets serve different functions in a portfolio. Bonds give investors protection if there’s an economic slowdown, whereas cash doesn’t.

Residential real estate: the gift that keeps on giving

Residential real estate dwarfs all other asset classes in Australia. Valued at $10.3 trillion, it’s almost 3x the size of the superannuation sector and 3.7x the size of the ASX.

After a sharp pullback in 2022, real estate has come back again. Housing prices have risen 7% over the past 12 months across Australia. In capital cities, they’re up 8.2%. Perth was the strongest market, rising 14%, with Brisbane and Sydney the next strongest. Perth, Adelaide, and Brisbane, now have real estate prices back at record highs, and Sydney’s are not too far away.

Source: CoreLogic

If I’d told you in April 2022, that rates would rise by 425 basis points over the next 19 months and that housing prices would be at or near record highs, you probably would have sent me to the nearest psychologist. But as mentioned earlier, the ‘mortgage cliff’ fears haven’t been realised as people had enough cash in reserve to handle the higher rates.

It’s not only that demand has held up. Supply has been pitiful as construction firms struggle to meet costs, and governments and councils make big promises yet fail to deliver on land releases and development approvals.

The undersupply is reflected is rents having increased by 8.1% nationwide over the past year. It’s interesting to me that even coming off a Covid-inspired boom, regional rentals have also held up remarkably well (commercial property and other assets have been hit much harder).

Source: CoreLogic

Where does that leave valuations for residential housing? As has been the case for a long time, they’re terrible.

Nation-wide, the average rental yield is 3.7%. In capital cities, it’s 3.5%. In Sydney and Melbourne, it’s 3% and 3.4% respectively. These are gross yields, before costs.

Source: CoreLogic

These yields don’t make sense from a valuation perspective. They significantly trail the risk-free rate of 4.35%.

Buying residential housing is relying on capital gains over time. And those capital gains are dependent on governments continuing to undersupply the market and juice demand through subsidies such as the first homeowners grant and negative gearing. Governments have had homeowners backs for a long time, and it’s a reasonable bet they’ll continue to in future.

The main potential snag with that is with affordability. Over the past 15 years, income growth has been anemic, and as a result, people have had to take on more debt to be able to afford ever expensive housing. With rates where they are now, Australians are practically maxed out on debt. That means for house prices to continue to rise, they’ll be more reliant in income growth than previously.

Either way, valuations don’t stack up to me.

The extraordinary bounce in US stocks

12 months is a long time in stock markets. In 2022, the S&P 500’s total return was -18%. This year to date, that’s swung around to +22%. Large cap stocks, especially the ‘Magnificent Seven’ have led the way. The Nasdaq 100 has jumped an astonishing 48% in 2023.

Not a day goes by without a commentator mentioning the crowding of investors into US large caps and tech stocks. But it isn’t just something that’s happened this year. Since 2011, the Nasdaq has returned 18% per annum (p.a.) in price terms, while the S&P 500 is up 13% p.a. Yet, over the same period, US mid-caps have returned an annualized 10% p.a. while US small caps have risen 8% p.a.

What’s led to this disparity in returns? Software “eating the world” and the rise of artificial intelligence may be factors. The increasing influence of passive investing could also be a factor. As could the growing global dominance of the US economy as China slips.

Whatever the reasons, they’ve left US large cap valuations looking stretched while the rest of the market seems less so. The S&P 500 is trading at a trailing price-to-earnings ratio (PER) of 21.2x and a forward PER of 18.7x. Yet, midcaps and small caps are both trading at an undemanding forward PER of less than 14x.

Some investors are betting that the concentrated rally in large-cap tech stocks will broaden to include mid and small caps in 2024. That’s not an unreasonable assumption. For long-term investors too, valuations at the small end of the US market look far more compelling than at the large end.

Australian stocks: boring is beautiful?

Compared to the euphoria of the US market, the ASX has been decidedly dull in 2023. The ASX 200 and All Ordinaries have barely risen in price terms, and up more than 4% when including dividends.

The difference in performance can be partly put down to Australia lacking the large-cap tech stocks that the US has. The ASX relies far more on banks, where earnings have been pedestrian, and resources, where earnings have struggled.

The All Ordinaries, trading at a trailing PER of 17x, doesn’t look especially exciting. That PER is deceptive though as there are considerable differences in valuations between the different sectors. The largest sectors of financials and resources trade at much lower multiples than industrials. That reflects both their cyclicality and earnings potential.

Does the ASX offer value, then? The market here has healthy dividends with limited prospects for capital gain. That may not be a bad thing, though. If investors can get close to a 4.5% fully franked dividend with some earnings growth, that should produce nice returns in the long run. And it’s not hard to see decent earnings growth as Australia’s economic outlook seems bright, given we have plentiful resources to fuel the energy transition, strong population growth, abundant capital via the superannuation sector, and low government debt.

Of all the assets, ASX stocks seem to offer the best value.

James Gruber is an assistant editor at Firstlinks and Morningstar.com.au