I have now been in the investment world for 40 years. I first looked at the lessons I learned in 2019. But they haven’t changed much since. Much has happened over the last 40 years with each new crisis invariably labelled ‘unparalleled’ and a ‘defining event’: the 1987 crash; the US savings and loan crisis and the recession Australia ‘had to have’ around 1990; the Asian/LTCM crisis in 1997/1998; the late 1990s tech boom and the tech wreck in 2000; the mining boom and bust; the GFC around 2008; the Eurozone crisis that arguably peaked in 2012 but keeps recurring; China worries in 2015; the pandemic of 2020; and the resurgence of inflation in 2021-22. The period started with deregulation and globalisation but is now seeing reregulation and de-globalisation. It’s seen the end of the Cold War, US domination and the rise of Asia and China but is now giving way to a new Cold War. And so on. But the more things change the more they stay the same. And this is particularly true in investing. So, here’s an update of the nine most important things I have learnt over the past 40 years.

#1 There is always a cycle – stuff happens!

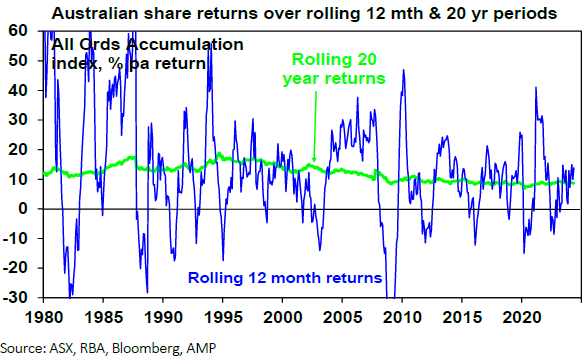

A constant is the endless phases of good and bad times for markets. Some relate to the 3-to-5-year business cycle, and many of these are related to the crises listed above that come roughly every 3 years. See the next chart. Some cycles are longer, with secular swings over 10 to 20 years in shares.

Debate is endless about what drives cycles. But all eventually contain the seeds of their own reversal and often set us up for the next one with its own crisis, often just when we think the cycle is over. So cycles & crisis are not going away. Ultimately there is no such thing as ‘new normals’ and ‘new paradigms’ as all things must pass. Also, shares often lead economic cycles, so economic data is often of no use in timing turning points in shares.

#2 The crowd gets it wrong at extremes

Cycles show up in investment markets with reactions magnified by bouts of investor irrationality that take them well away from fundamentally justified levels. This flows from a range of behavioural biases investors suffer from and so is rooted in investor psychology. These include the tendency to project the current state of the world into the future, the tendency to look for evidence that confirms your views, overconfidence, and a lower tolerance for losses than gains. While fundamentals may be at the core of cyclical swings in markets, they are often magnified by investor psychology if enough people suffer from the same irrational biases at the same time. From this it follows that what the investor crowd is doing is often not good for you to do too. We often feel safest when investing in an asset when neighbours and friends are doing the same and media commentary is reinforcing the message that it’s the right thing to do. This ‘safety in numbers’ approach is often doomed to failure. Whether it’s investors piling into Japanese shares at the end of the 1980s, Asian shares in the mid-1990s, IT stocks in 1999, US housing and credit in the mid-2000s. The problem is that when everyone is bullish and has bought into an asset there is no one left to buy but lots of people who can sell on bad news.

#3 What you pay for an investment matters – a lot!

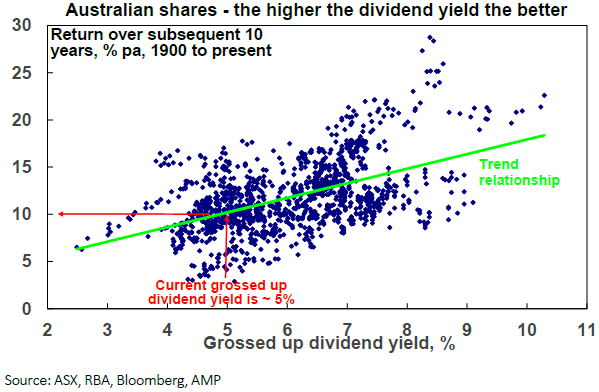

The cheaper you buy an asset the higher its return potential. Guides to this are price to earnings ratios for shares (the lower the better) and yields, ie, the ratio of dividends, rents or interest to the value of the asset (the higher the better). Flowing from this it follows that yesterday’s winners are often tomorrow’s losers – as they get overvalued and over loved. But many find it easier to buy after shares have had a strong run because confidence is high and sell when they have had a big fall because confidence is low.

#4 It’s hard to get markets right

The 1987 crash, tech wreck and GFC all look obvious. But that’s just Harry Hindsight talking! Looking forward no-one has a perfect crystal ball. As JK Galbraith observed, “there are two kinds of forecasters: those who don’t know, and those who don’t know they don’t know.”

Usually the grander the forecast – calls for ‘great booms’ or ‘great crashes’ – the greater the need for scepticism as such calls invariably get the timing wrong (so you lose before it comes right) or are dead wrong. Market prognosticators suffer from the same psychological biases as everyone. If getting markets right were easy, prognosticators would be mega rich and would have stopped long ago. Related to this, many get it wrong by letting blind faith – ‘there is too much debt’, ‘house prices are too high’ – get in the way of good decisions. They may be right one day, but an investor can lose a lot of money in the interim. The problem for ordinary investors is that it’s not getting easier. The world is getting noisier with the rise of social media which has seen the flow of information and opinion go from a trickle to a flood and the prognosticators get shriller to get clicks. Even when you do it right as an investor, a lot of the time you will be wrong – just like Roger Federer who noted that while he won almost 80% of the 1526 singles matches in his career, he won only 54% of the points, or just over half. It’s unlikely to be much better for great investors. For most investors its best to focus on the long-term trend in returns – ie, the green line as opposed to the blue line in the first chart.

#5 Investment markets don’t learn, well not for long!

German philosopher Georg Hegel observed “The one thing that we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history”. This is certainly the case for investors where the same mistakes are repeated over and over as markets lurch from one extreme to another. This is despite after each bust, many say it will never happen again, and the regulators move in to try and make sure it doesn’t. But it does! Often just somewhere else or in a slightly different way. Sure, the details change but the pattern doesn’t. As Mark Twain is said to have said: “History doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes”. Sure, individuals learn and the bigger the blow up, the longer the learning lasts. But there’s always a fresh stream of new investors so in time collective memory dims.

#6 Compound interest is key to growing wealth

This one was drummed into me many years ago by my good friend Dr Don Stammer. Based on market indices and the reinvestment of any income flows and excluding the impact of fees and taxes, one dollar invested in Australian cash in 1900 would today be worth around $259 and if it had been invested in bonds it would be worth $924, but if it was allocated to shares it would be worth around $879,921. Although the average annual return on Australian shares (11.6% pa) is just double that on Australian bonds (5.6% pa) over the last 124 years, the magic of compounding higher returns leads to a substantially higher balance over long periods. Yes, there were lots of rough periods along the way for shares, but the impact of compounding returns on wealth at a higher long-term return is huge over long periods. The same applies to other growth-related assets such as property. So, to grow your wealth you need to have a decent exposure to growth assets.

#7 It pays to be optimistic

Benjamin Graham observed that “to be an investor you must be a believer in a better tomorrow”. If you don’t believe the bank will look after your deposits, that most borrowers will pay back their debts, that most companies will grow their profits, that properties will earn rents, etc, then you should not invest. Since 1900, the Australian share market has had a positive return in roughly eight years out of ten and for the US share market it’s roughly seven years out of 10. So, getting too hung up worrying about the two or three years in 10 that the market will fall risks missing out on the seven or eight years when it rises.

#8 Keep it simple, stupid

We have a knack for overcomplicating investing. And it’s getting worse with more options, more information, more apps and platforms, more opportunities for gearing, more fancy products, more rules and regulations. But when we overcomplicate things we can’t see the wood for the trees. You spend too much time on second order issues like this share versus that share or this fund manager versus that fund manager, or the inner workings of a financially engineered investment so you end up ignoring the key drivers of your portfolio’s performance – which is its high-level asset allocation across shares, bonds, and property. Or you have investments you don’t understand or get too highly geared. So, it’s best to keep it simple, don’t fret the small stuff, keep the gearing manageable and don’t invest in products you don’t understand.

#9 You need to know yourself

The psychological weaknesses referred to earlier apply to everyone, but smart investors seek to manage them. One way to do this is to take a long-term approach to investing. But this is also about knowing what you want. If you want to take a day-to-day role in managing your investments then regular trading and/or a self-managed super fund (SMSF) may work, but that will require a lot of effort to get right and will need a rigorous process. If you don't have the time and would rather do other things like sailing, working at your day job, or having fun with the kids then it may be best to use managed funds or a financial planner. It’s also about knowing how you would react if your investment just dropped 20% in value. If your reaction were to be to want to get out, then you will either have to find a way to avoid that as you would just be selling low and locking in a loss or if you can’t then you may have to consider an investment strategy offering greater stability over time and accept lower potential returns.

What does all this mean for investors?

All of this underpins what I call the Nine Keys to Successful Investing:

1. Make the most of the power of compound interest. This is one of the best ways to build wealth, but you must have the right asset mix.

2. Don’t get thrown off by the cycle. Cycles can throw investors out of a well thought out investment strategy. And they create opportunities.

3. Invest for the long-term. Given the difficulty in getting market moves right in the short-term, for most it’s best to get a long-term plan that suits your level of wealth, age and tolerance of volatility and stick to it.

4. Diversify. Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. But also, don’t over diversify as this will just complicate for no benefit.

5. Turn down the noise. After having worked out a strategy that’s right for you, it’s important to turn down the noise on the information flow and prognosticating babble now surrounding investment markets and stay focussed. In the digital world we now live in this is getting harder.

6. Buy low, sell high. The cheaper you buy an asset, the higher its prospective return will likely be and vice versa.

7. Beware the crowd at extremes. Don’t get sucked into the euphoria or doom and gloom around an asset.

8. Focus on investments you understand and that offer sustainable cash flow. If it looks dodgy, hard to understand or has to be based on odd valuation measures, lots of debt or an endless stream of new investors to stack up then it’s best to stay away.

9. Seek advice. Given the psychological traps we are all susceptible to and the fact that investing is not easy, a good approach is to seek advice.

Dr Shane Oliver is Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist at AMP. This article has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs.