Australian banks have certainly taken criticism over the last couple of years, much of it deserved and some of it produced for the pleasure of the media. Banks have been in a never-ending cycle of public-attested mistakes. While culture and greed are often cited, I doubt this is really the case.

One area worth exploring is whether banks have the right management and governance experience for the modern business environment. This is not a question of a director’s ‘smarts’ but rather if traditional experiences are still as relevant.

Most recent bank losses have little to do with lending losses. They have been operational failures.

CBA copped a $700 million dollar fine for its “software error” causing breaches with AUSTRAC’s anti-money laundering (AML) rules.

Westpac lost its CEO and Chairman due to AML failures on small international transactions in what AUSTRAC said was due to a lack of "appropriate IT systems and automated solutions”.

In many respects, a cold analysis of banking governance suggests the above examples were accidents waiting to occur.

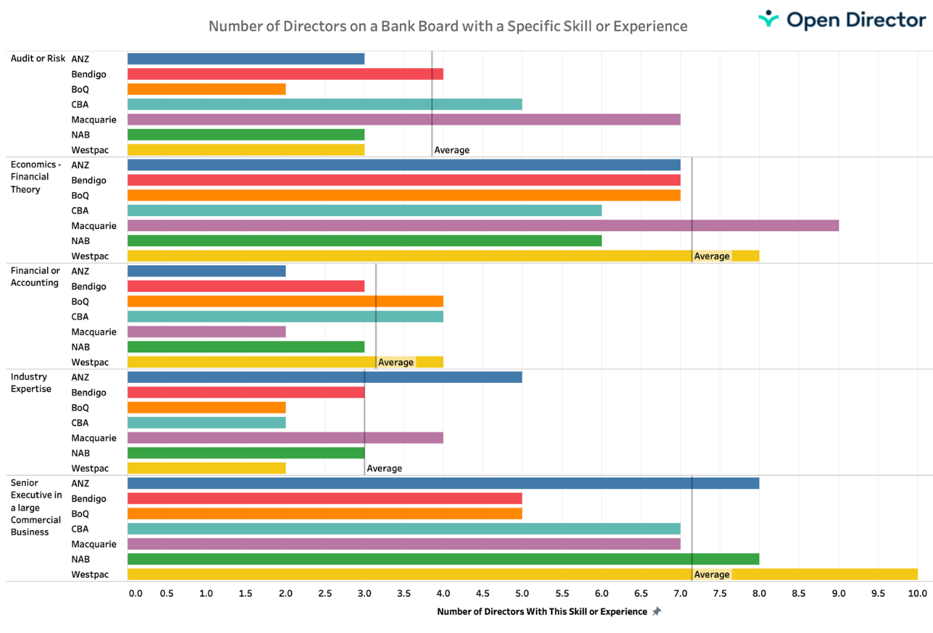

First, the good news. When running a heatmap over the skills of bank directors, they rate well in the core skills of ‘Risk and Audit’, ‘Economic and Financial Theory’, ‘Accounting’, ‘Industry Expertise’ and holding responsibilities in ‘Large Commercial Business’.

But times are changing at an ever-increasing pace. The required skills from a director ten years ago are not those required today. Banks now resemble huge digital machines run at high speed sitting on top of large capital bases. Staff numbers are continually cut and those remaining have more diverse and larger responsibilities.

But times are changing at an ever-increasing pace. The required skills from a director ten years ago are not those required today. Banks now resemble huge digital machines run at high speed sitting on top of large capital bases. Staff numbers are continually cut and those remaining have more diverse and larger responsibilities.

Unfortunately, many bank directors lack some really important business experience. They don’t understand technology, they don’t have operations skills and they are light on human resource experience. These skills are thought to exist because they may have held senior roles like a CEO of a large company.

The reality is you need hands-on experience and scar tissue from being deeply involved in technology and operations to know where the subtle but real risks exist.

Technology is moving under our feet as it evolves and living with these new risks and ambiguity can only be learnt on the front line. Being a ‘good people manager’ will only give a partial credit for these complex skills.

When we look at these new skill requirements our directors are coming up short.

This second table clearly shows that banks could materially improve the diversity of skills on a board. Historically, many would argue that these skills are of second order. Directors need to know how to run big companies with large staff numbers.

This second table clearly shows that banks could materially improve the diversity of skills on a board. Historically, many would argue that these skills are of second order. Directors need to know how to run big companies with large staff numbers.

But that is no longer the case. Knowing how to run technology is perhaps even more important in avoiding a scandal that makes the front page of the Australian Financial Review than in driving commercial success.

Donald Hellyer is Director of OpenDirector and CEO of the development company BigFuture.