Earlier this month, famed US hedge fund investor David Einhorn gave one of the more fascinating interviews I’ve heard in recent years. For those that don’t know him, Einhorn has run Greenlight Capital since 1996 and is well-known for having shorted Lehmann Brothers prior to the 2008 bust.

In the interview with Bloomberg, Einhorn declares that passive investing has fundamentally broken markets. And that the changes wrought from passive investing have meant he’s had to change his method of value investing to stay in business.

His claim that passive investing is distorting markets isn’t new. Active managers have long complained about the issue. Yet Einhorn makes some important observations about how he thinks indexing is changing the structure of markets:

“There’s all the machine money and algorithmic money … which doesn’t have an opinion about value. It has an opinion about price. Like what is the price going to be in 15 minutes? And I want to be ahead of that or zero-day options. What is the price of the s and p or whatever stock you’re doing for today, what’s it going to be in the next half hour, two hours, three hours? Those are opinions about price. Those are not opinions about value. Passive investors have no opinion about value. They’re going to assume everybody else’s done the work, right?

And then you have all of what’s left of active management and so much of it, the value industry has gotten completely annihilated. So, if you have a situation where money is moved from active to passive, when that happens, the value managers get redeemed, the value stocks go down more, it causes more redemptions of the value managers, it causes those stocks to go down more.

… And, all of a sudden, the people who are performing are the people who own the overvalued things, that are getting the flows from the indexes, that are getting you take the money out of the value, put it in the index, they’re selling cheap stuff and they’re buying, you know whatever the highest multiple, most overvalued things … in disproportionate weight. So, then the active managers who participate in that area of the market get flows and they buy even more of that stuff. So. what happens is instead of stocks reverting toward value, they actually diverge from value. And that’s a change in the market and it’s a structure that means that almost the best way to get your stock to go up is to start by being overvalued.”

How Einhorn has adapted to the changes in markets is intriguing. Einhorn had a fantastic track record in the almost 20 years to 2015. Then, he had two awful years and three mediocre ones. Some of you may recall that news publications started to question his ability during this time, if not writing him off altogether.

How Einhorn came through this period is instructive. He analysed his period of underperformance and realised that he had continually bought cheap stocks and when these stocks handily beat earnings estimates, they weren’t being re-rated by the market. Because they were outside of indices and not included in ETFs, there were few buyers for these stocks.

This happened often enough that it made him change his investment style:

“… what we have to do now is be even more disciplined on price. So, we’re not buying things at 10 times or 11 times earnings. We’re buying things at four times earnings, five times earnings, and we’re buying them where they have huge buybacks, and we can’t count on other long only investors to buy our things after us. We’re going to have to get paid by the company. So we need 15-20% cash flow type of type of numbers. And if that cash is then being returned to us, we’re going to do pretty well over time … you’re literally counting on the companies to make that happen for you.”

Since Einhorn has made these changes, he’s gone back to handily beating the market benchmarks.

Passive a goliath in US, not so much in Australia

Einhorn’s comments raise several important questions about today’s markets.

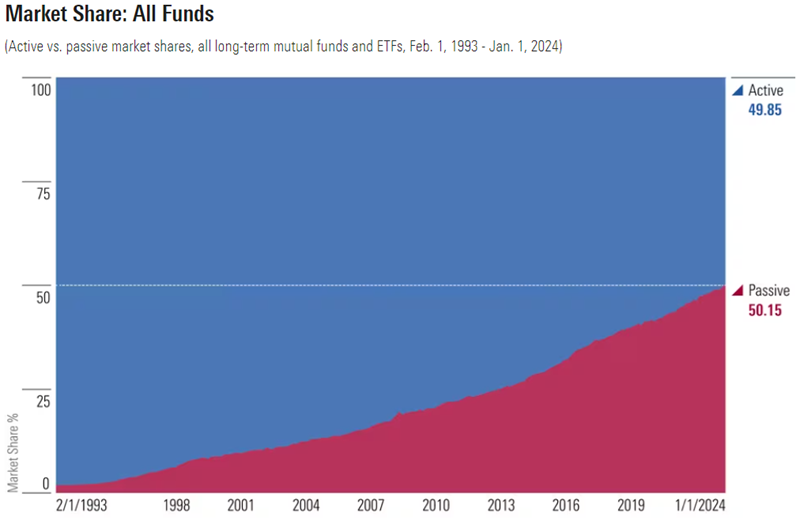

There’s little doubt that passive investing is growing quickly and taking market share from active funds. Last month, for the first time, passively managed funds in the US controlled more assets than did their actively managed competitors.

Source: Morningstar

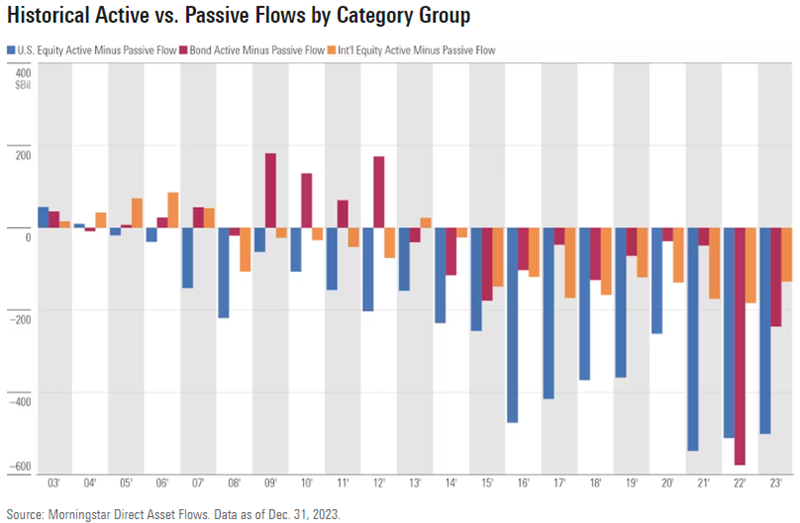

That’s after passive US equity funds took in US$244 billion in 2023, while active funds had outflows of US$257 billion, continuing a long-running trend.

The relentless growth in passive funds has resulted in the largest ETF and index providers growing into behemoths. Blackrock now has A$14.5 trillion under management, while Vanguard has A$11 trillion.

The growth in passive funds in the US has been mirrored in Australia. Last year, the ETF industry here grew 33% year-on-year to $177.4 billion in funds under management, according to BetaShares.

Yet unlike in the US, ETFs are relatively small fry still compared to active funds. The latter, which include industry funds, retail funds and other fund managers, have funds under management at close to $4.5 trillion, about 25x the size of the ETF market.

And ETF insiders suggest passive ownership of the ASX 200 is close to 10%, a far cry from the larger share it has in the US.

Yet, further growth in passive funds seems likely, with investors attracted to the simple and low-cost access that ETFs provide to markets, as well as their performance versus active funds.

The other big market trend

Along with the rise of passive funds, there’s also been an increasing institutionalisation of markets. In the US, professional money managers accounted for 10% of share ownership after the Second World War. That’s risen to close to 67% today. It means that in the 1940s and 1950s, active fund managers had far fewer direct competitors - their main competitors were individuals.

Professional fund managers are hired and fired according to how they perform compared to benchmarks. As passive funds pile into the stocks included in benchmarks, it’s likely that active managers are being forced into buying into the same stocks to keep up with these benchmarks. If they’re buying into the same stocks as passive funds, and charging higher fees to clients, it isn’t a surprise that active funds have consistently underperformed passive ones over the past 10 years.

It’s why Einhorn is complaining that passive funds are breaking markets. He’s saying individual investors are fleeing into passive funds, and these funds are buying stocks included in indices, which are principally the larger companies. And they are doing that automatically, without regard to price. Also, active funds, to keep up with benchmarks and passive funds, are buying into the same stocks.

According to Einhorn, stocks that are outside of benchmarks are being ignored by individual and professional investors. Even if these stocks are undervalued and their fundamentals are improving, there are few if any buyers for these companies in the current market.

Are Einhorn’s concerns valid?

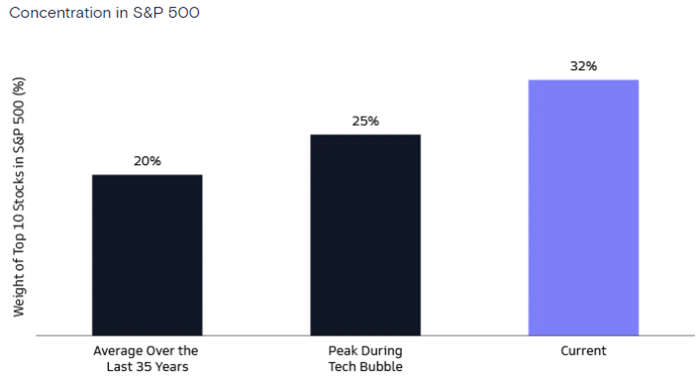

There is some anecdotal and academic evidence to support Einhorn’s claims. For instance, it does seem larger cap stocks are getting more investor love than at any time in recent history. Late last year, Goldman Sachs did a study that found the S&P 500 is more concentrated than it’s ever been. The average weight of top 10 stocks in the S&P 500 index has been 20% over the past 35 years. During the dot-com bubble, the combined weight of top 10 stocks peaked at 25%. Today, the figure stands at 32%.

Source: Goldman Sachs

That’s led to significant outperformance from large cap stocks versus small caps. Last year, US large caps returned 26.2% compared to US small caps’ 16.8%. Since 2011, large caps there have returned 382%, or 13% annualized, versus small caps’ 208%, or 9% per annum.

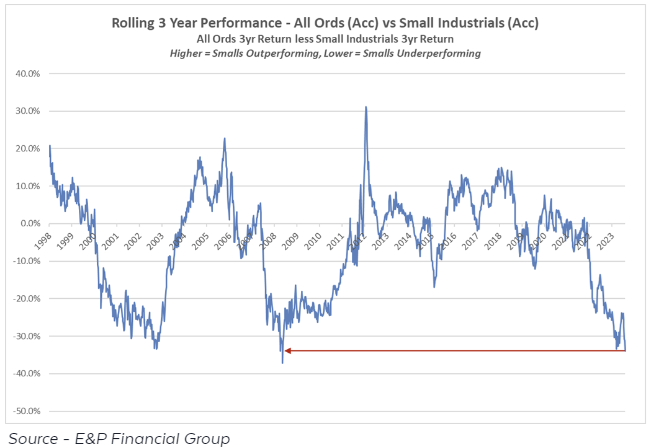

The story of large cap outperformance has also been evident in Australia.

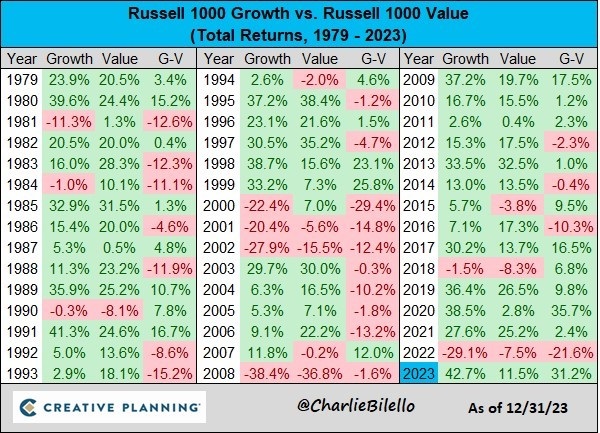

The largest stocks have tended to be ‘growth’ stocks, and growth has destroyed value over the past 15 years.

There’s also academic evidence that backs some of Einhorn’s assertions. In a 2022 paper, ‘How Competitive is the Stock Market’, UCLA’s Valentin Haddad and colleagues found that the rise of passive investing was distorting price signals and pushing up the volatility of the US market. The paper examined institutional investors and concluded that the rise of passive investors’ share of the US market over the past two decades “has led to substantially more inelastic aggregate demand curves for individual stocks, by 15%”. Passive investors have a demand elasticity of zero, because they automatically buy stocks without regard to whether it’s cheap or not. If a stock is cheap, demand from passive investors won’t increase. In theory, that should mean other investors step in to make up the demand shortfall in stocks, but the paper suggested that hadn’t happened.

Counterarguments to Einhorn

The anecdotal evidence mentioned above is just that: anecdotal. The academic evidence is also relatively new and untested.

There are several potential counterarguments to Einhorn’s assertions that passive investing is distorting markets and prices:

- The influence of passive funds on market prices may be less than claimed. Passive funds typically have low turnover, of 10-20% each year. That compares to active funds of +50%. Trading sets prices, and therefore the influence of passive investing on pricing may be overstated.

- If stock markets and price discovery are becoming less rational, that should help active investors rather than hinder them. If markets are fully rational and price stocks perfectly, there would be no role for active investors.

- Indexing may aid price discovery rather than hinder it. For example, it increases the supply of lendable shares and thus enables short selling.

In short, there may be some truth to Einhorn’s complaints though they are likely exaggerated.

The danger of passive investing for markets

Nonetheless, Einhorn is right to point out the changes that passive investing is bringing to markets. If passive investors are crowding into the large cap stocks that dominate indices, and active investors are mimicking them to keep up with performance benchmarks, it’s logical that the reverse can happen too. That is, in a market downturn, there may be a rush for the exits as both passive and active investors get out of large cap stocks. This may become even more of an issue as passive funds continue to take market share from active managers.

There hasn’t been a real test of this sort for passive investing. That said, markets did remain relatively orderly in 2022 when they were hit hard. A larger market downturn would be a real test for passive investing and the changes it’s made to markets. Whether it leads to a shakeout in passive funds is also an open question.

Investors can learn from Einhorn

You must credit Einhorn for changing his investment style to adapt to the changes that he sees in markets. Here was a guy that was known as one of the best hedge fund investors in the world, going through an extended rough patch. He could have easily doubled down on the strategy that had brought him results and fame over the previous years. Instead, he questioned that strategy and decided to change tack.

It would have been a big risk to change investment style at that time. He was under a lot of pressure from his clients and the media. If it went wrong, he would have looked foolish, and it might have been game over for his fund. Instead, it helped him turn things around.

Investors can learn a lot from Einhorn’s objective assessment of his underperformance, the reasons behind it, and changing his investment process and style to address the issues.

James Gruber is an assistant editor at Firstlinks and Morningstar.com.au