Aside from fuelling global inflation, rising commodities prices are particularly good for commodities exporters like Australia. Last week’s Federal Budget was little more than a vote-buying cash splash, funded by unexpected windfall mining royalties and taxes.

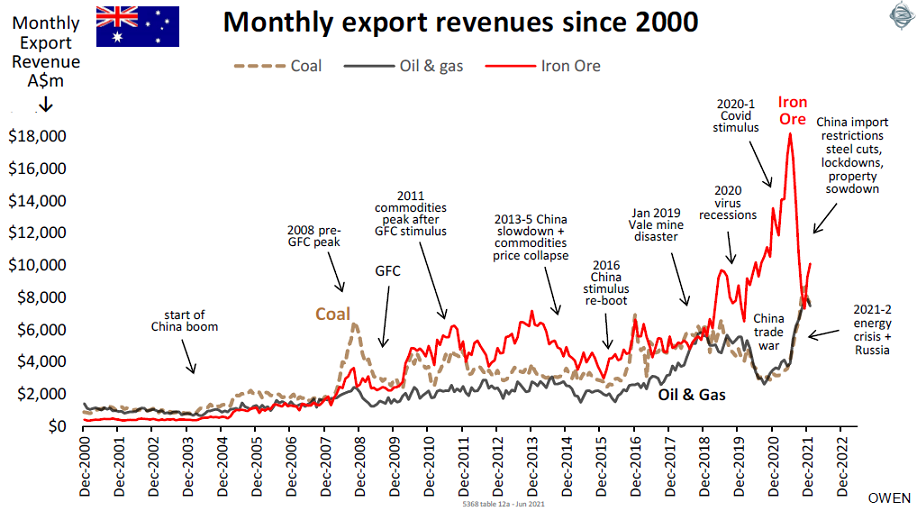

The rise in commodities prices over the past two years has been a combination of increasing global demand as the world recovers from Covid lockdown recessions, and also favourable supply restrictions, especially in the case of our two largest export earners – iron ore and coal, and now gas with the Russia-Ukraine war. China has been extending its restrictions on its imports from Australia since the trade war began in 2018 and especially over the past year, but these have mostly been picked up by other buyers across Asia.

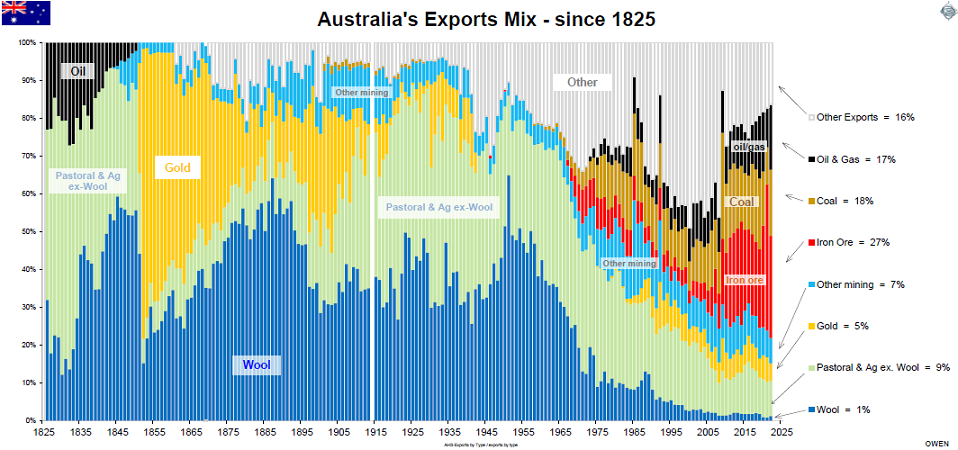

Post-settlement Australia has always relied on raw commodities exports to raise the foreign exchange needed to import everything we need for our daily lives. Unlike most ‘banana republics’, Australia has been blessed with a host of different types of commodities – from the land, the earth beneath the land, and the sea. Here is our updated chart of Australia’s export mix over the past two centuries. It is a remarkable story of dramatic shifts in our export mix over time – starting with oil (from whales and seals!), to crops, wool, then gold and base metals in the 19th century, back to pastoral, wool and crops for most of the 20th century, then the rise of East Asia built with our coal, iron ore and base metals after WW2, and back to oil and gas. This illustrates not only our vast diversity of resources, but also the ability to adapt and prosper from changing global economic and political conditions.

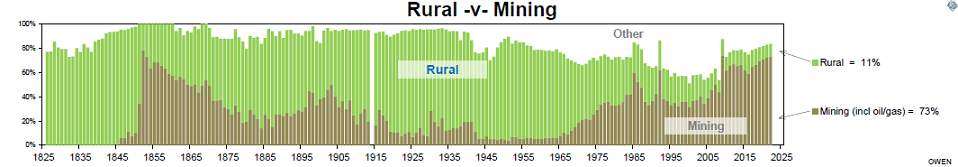

The second chart shows the changing mix between rural and mining exports. Rural has dominated for most of the whole period, with the notable exception being the 1850s gold rush. The turning point was 1960. At the time, wool made up 50% of total export revenues, but the lifting of the iron export embargo in 1960 diversified the export base and dramatically reduced Australia’s vulnerability to the vagaries of the weather. Mining finally overtook rural in the mid-1980s and has dominated ever since. Australia may have got rich riding the sheep’s back, but it is a far more diversified and robust export mix now.

Australia’s commodities export revenues

The next chart shows monthly export revenues from the three ‘big ones’ (iron ore, coal and oil/gas) since 2000. Iron ore prices and revenues had an extraordinary spike after the Vale mine closures at the start of 2019. The Covid restrictions catapulted Australia to overtake Brazil as the world’s largest iron ore exporter, and also overtake South Africa as the world’s largest exporter of coal. While China’s restrictions have hit coal and agricultural exports, and now iron ore, it has not all been bad news. Despite rising Canberra-Beijing tensions, China has now overtaken Japan as our largest LNG buyer.

How long will the commodities boom last?

In the case of most commodities, the current price spikes are probably temporary. Most of the spikes are due mainly to supply constraints with a range of causes, from Covid lockdowns, unrelated disasters (like mine tailings dam collapses), trade war restrictions, a host of unrelated weather events, and now the Russia-Ukraine war. In time these supply constraints will ease.

The global shift to renewables has also led to elevated prices of old fossil fuels for probably longer than anticipated.

The bigger picture is that price rises always trigger increased investment in new sources of supply and in alternatives. New developments always take time, stretching from a few months to many years in some cases. The history of commodities prices is riddled with price rises (for whatever reason) followed by surplus supply causing price collapses when new supply and/or alternatives catch up to, and then overtake demand. The price collapse leads to bankruptcy of some producers (which reduces supply), and a hiatus in new development. Meanwhile rising demand (from rising populations and rising living standards) slowly but surely catches up to, and over-takes supply, causing prices to rise once again. This kicks off the whole cycle in an endless cycle of booms and busts fuelled by these supply time lags.

The key to success with investing in commodities markets (and producers) is understanding these commodities prices cycles and getting the timing right.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.