This time last year, I wrote an article called, ‘Australian stocks will crush housing over the next decade’, which got a lot of feedback from subscribers.

I thought it would be a good idea to do something rarely done in the financial media: to hold myself accountable for a forecast. And that doing an annual update and what had changed would be helpful for readers.

Here is that update.

Before I get to it, let’s recap the reasons I gave last December for suggesting that the ASX shares would beat housing returns over the next 10 years. The reasons were simple enough. I surmised that housing was hideously overvalued, about 40% overvalued on my estimates. It made housing in Australia one of the most expensive assets in the world. Even more expensive than the ‘Magnificent Seven’ stocks at the time, which themselves were considered tremendously expensive yet had infinitely better growth prospects than residential property here.

Because of this overvaluation, I suggested that there was a high probability that future returns from housing would be mediocre, in the range of 2-5% over the next decade. That was using relatively optimistic assumptions too.

Conversely, Australian shares last December appeared reasonable value. They were trading largely in line with their long-term averages. Assuming average earnings growth with the then dividend yield of 4.4%, returns on shares would be in the range of 6.5-10% over the next 10 years, in my view.

The scorecard one year later

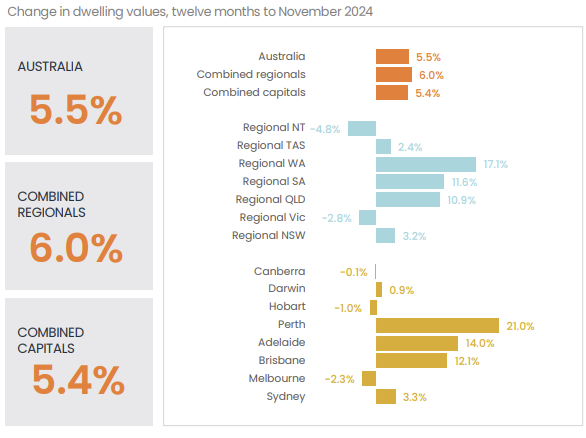

One year into the 10-year forecast, here is the scorecard: from December 1, 2023 to November 30, 2024, the ASX 200 was up 19% in price terms, and 23% including dividends. That compares to a 5.4% gain for Australian housing in the capital cities over the same period.

ASX 200 index

Source: Morningstar

Source: CoreLogic

So far, Australian shares have crushed housing. Yet, it’s early days and there’s much to play out.

The fascinating part of the past year was that the gain in shares was driven entirely from an increase in valuation. Earnings for stocks were relatively flat over the period. However, the price attached to those earnings increased, with the price-to-earnings ratio (PER) rising from 17x to 22x.

The extraordinary run of the banks was a big reason behind the jump in the market’s PER. For instance, Commonwealth Bank (ASX:CBA) was up 52% over the period, excluding dividends. Amazingly, earnings for CBA went backwards during that time! Trading at 28x PER, CBA is now the most expensive bank in the developed world, and it’s daylight behind them.

Source: Morningstar

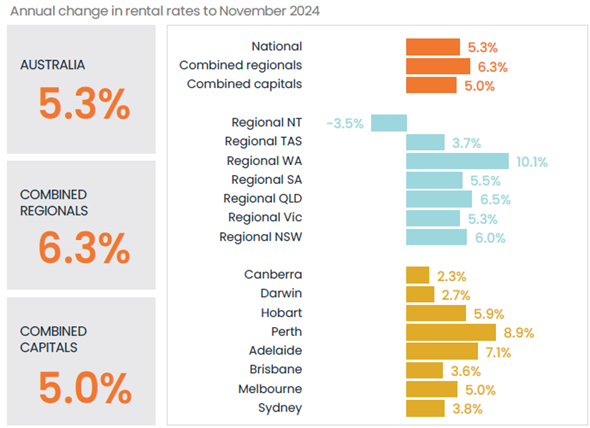

Where the fundamentals for shares were pedestrian, those for housing held up reasonably well. Rents increased 5% across the capital cities. Meanwhile, valuations softened marginally.

Source: CoreLogic

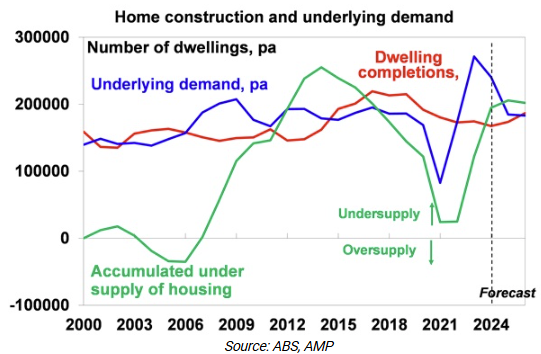

Supply of housing has remained tight. There’s an accumulated shortfall of around 200,000 dwellings. The reasons for the supply shortfall are many. From a lack of development approvals combined with the rise of NIMBYs (not in my backyard) to capacity constraints to, construction firms struggling to stay afloat amid cost pressures.

Meantime, demand has held up remarkably well even with higher rates. Surging immigration numbers have helped with this.

Remarkable to me is the continued upswing in investors into housing. Loans to investors were up 30% in the year to September this year. And investors made up 37% of new housing loans. While that type of number is considered normal in Australia, it’s anything but that when compared globally.

What do valuations look like now?

Where does that leave valuations now? For housing, not much has changed. It remains extraordinarily overvalued on key valuation metrics. In my previous article, I suggested that one way of looking at housing valuation was to compare it to risk-free bond yields. The risk-free bond yield (the 10-year yield) in December last year was 4.11%. That compared to the rental yield on housing of 3.5% (that’s a generous interpretation as this is a gross yield before taxes and expenses).

I proposed back then that all assets are essentially priced off this risk-free rate, and that for taking the risk of owning an asset, an investor would demand a premium to that risk-free rate. The extent of the premium was open to debate, though I put that a reasonable premium for housing should be around 1.5%.

Applying that premium suggested housing’s fair value was around a yield of 5.61% compared to the then rental yield of 3.5%. That put housing at close to a 40% overvaluation versus the value ascribed to it back then.

Since last year, not a lot has changed. The 10-year bond yield has increased slightly to 4.25%. Meanwhile, the housing rental yield has remained at 3.5%. Therefore, on this metric, housing remains about 40% overvalued.

Other metrics support the overvaluation thesis. A 3.5% gross rental yield equates to a PER for housing of 29x (100 divided by 3.5). That doesn’t tell the full story though because that gross yield neglects taxes and costs. Add in a 30% tax, and that PER rises to 41x. Add in costs, and the PER almost certainly reaches +50x.

50x PER is almost 2,5x that of the ASX’s 22x. It’s also well above the 30.2x average forward PER of the Magnificent Six stocks, which are themselves considered expensive (including Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft, Nvidia, Meta, Apple, but excluding Tesla which trades at 113x PER).

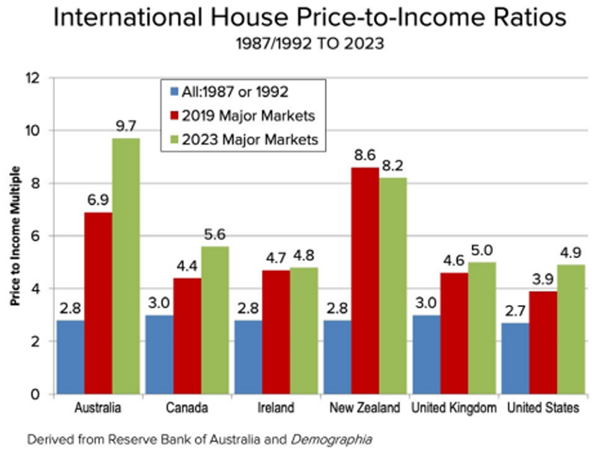

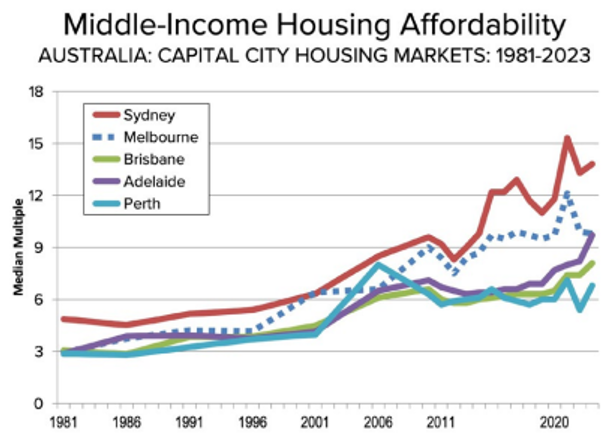

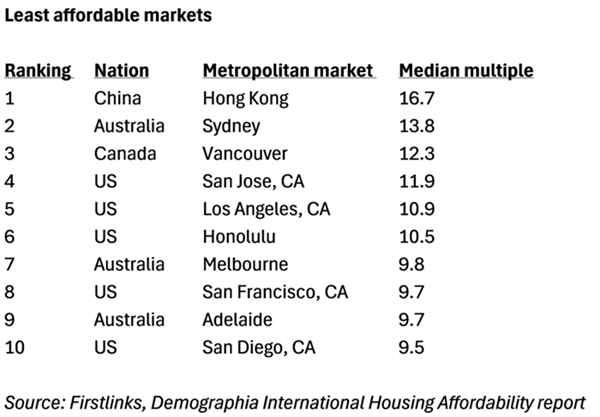

House prices also look stretched according to price-to-income ratios. In June, international consultants, Demographia, released its widely respected annual survey of residential property across eight countries. Its report suggested that Australia’s five major capital cities, excluding Canberra, Hobart, and Darwin, were either severely unaffordable, or impossibly unaffordable.

Demographia said that Australia’s median price-to-income multiple of 9.7x was more than 2x that of the US, and almost 2x that of the UK.

The report found three capital cities in Australia ranked among the top ten least affordable markets in the world. Even little old Adelaide, where I’m from, ranked ninth and was considered less affordable than New York!

Whichever way you cut it, housing in Australia remains expensive.

As for shares, they look less attractive than they did a year ago. At 22x, they’re about 30% above the long-term average PER. And earnings growth looks subdued in the near term, with minimal growth out of the banks, and the large miners being hit by lower iron ore prices.

Future returns

I maintain my forecast of housing returns of 2-5% over the 10 years from December 1, 2023. That forecast was based off a starting net yield of 2.45%, in addition to 2.5% average rental earnings growth (compared to the 2% historical average). Assuming no change in valuations, that would give you an annual nominal return for housing of 4.95% (2.5% plus 2.45%).

Any cut to current steep valuations would result in a reduction to the nominal return.

One criticism I received last year was my assumption for rental growth. 2022-2023 saw extraordinary rises in rents and some expected that to continue. I didn’t, and that’s played out, with rental growth easing. Growth should slow further in the medium term as supply constraints loosen (they invariably will at some point).

For shares, I had forecast annual returns of 6.5-10%. That remains on track, even after the spectacular gains of the past year. Valuations have pushed the market higher, even though earnings have lagged. The market dividend yield has also come down, from 4.4% last year to 3.4% now. That makes the market less attractively valued and vulnerable to a pullback in the short term.

Long term however, the dividend yield plus conservative earnings growth of +3% should ensure decent returns from here.

Note I’ve changed the benchmark for share returns to the ASX 200 from the All Ordinaries Index used in the previous article. The former is easier to track over time and the differences between the two indices are minimal given the overlap in heavyweight stocks.

Note also that Firstlinks is normally sceptical of forecasts but this seemed a ‘no-brainer’ at the time even though few agreed.

James Gruber is an Editor at Firstlinks.