Economic growth is the central assumption underlying our political and economic systems. It is the mechanism relied upon for improving living standards, reducing poverty to now solving the problems of over indebted individuals, businesses and nations. All brands of politics and economics assume sustainable, strong economic growth, combined with the belief that governments and central bankers control the economy to bring this about. Like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Gatsby:

“[they believe in] the orgiastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter – tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther.”

Growth fuelled by debt

But strong growth is not normal, being a relatively recent phenomenon in human history. Moreover, recent economic activity and the wealth created relied on borrowed money and speculation. It was based upon the profligate use of mis-priced natural resources such as oil, water and soil. It relied on allowing unsustainable degradation of the environment. In 1954 German economist E.F. Schumacher identified the trajectory:

“Mankind has existed for many thousands of years and has always lived off income. Only in the last hundred years has man forcibly broken into nature’s larder and is now emptying it out at breathtaking speed which increases from year to year.”

Central to the problem is the level of indebtedness. Debt accelerates consumption, as borrowed funds are used to purchase something today against the promise of paying back the money in the future. Spending that would have taken place normally over a period of years is squeezed into a relatively short period because of the availability of cheap borrowing. Business over invests misreading demand, assuming that the exaggerated growth will continue indefinitely, increasing real asset prices and building significant over-capacity. Around 85% of the debt incurred over the last 30-35 years funded the purchase of existing assets or consumption rather than being used for creating new businesses or productive purposes which build wealth.

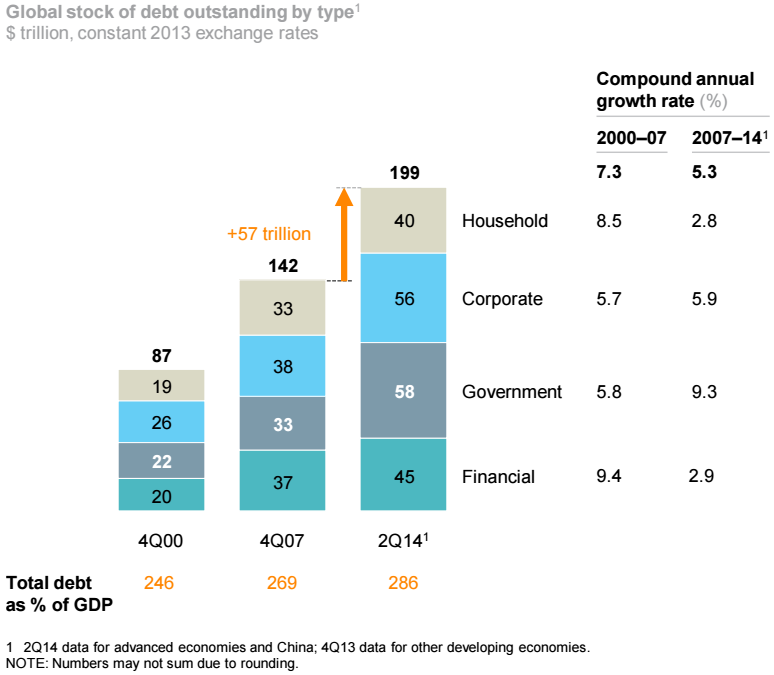

The problem of debt remains unaddressed. As a recent analysis by McKinsey Global Institute shows (see Table below), deleveraging has not even commenced.

Source: Richard Dobbs, Susan Lund, Jonathan Woetzel and Mina Mutafchieva (2015) Debt and (not much) deleveraging, McKinsey Global Institute.

Elegant financial engineering and ‘hopium’ economics cannot mask the problem of excessive leverage forever. The debt will have to be repaid out of future income or proceeds of asset sales, diminishing growth or savaging investment values. If as is likely this debt cannot be repaid, then it will be written off, resulting in an unprecedented loss of wealth for savers.

Pushing problems to the future

Compounding the problems of debt, resources and environment are challenges of slowing rates of meaningful innovation, lower improvements in productivity, demographics, inequality and exclusion.

The trade-offs are complex. Lower growth reduces environmental damage and conserves resources. But it lowers living standards and increases debt repayment problems. Faster growth lifts living standards. If the expansion is mainly debt driven, it adds to already high borrowing levels and increases environmental and resource pressures.

Lower commodity prices help boost consumption and growth. But it encourages greater use of non-renewable resources and accelerates environmental damage. Inflation reduces debt levels but penalises savers and adversely affects the vulnerable in poorer nations. Reducing free movement of goods and capital or currency devaluation assists an individual country, but the resulting economic wars between nations impoverishes everyone.

The approach to dealing with the challenges is flawed. In a Faustian bargain, policy makers sold the future originally for present prosperity and are now re-selling it for a precarious and short lived stability. There is a striking similarity between the problems of the financial system, irreversible climate change and shortages of vital resources like oil, food and water. In each area, society borrowed from and pushed problems into the future. Short-term profits were pursued at the expense of risks which were not evident immediately and that would emerge later.

Kicking the can down the road only shifts the responsibility onto others, especially future generations. By postponing the inevitable, the adjustment becomes larger and more painful. A slow, controlled correction of the financial, economic, resource and environmental excesses now may be serious but manageable. If changes are not made, then the forced correction will be dramatic and violent, with unknown consequences.

Less room to move

The world is remarkably sanguine about a new major crisis. During the last half-century each successive crisis has increased in severity, requiring progressively larger measures to ameliorate its effects. Over time, the policies have distorted the economy. The effectiveness of instruments has diminished. With public finances weakened and interest rates at historic lows, there is now little room for manoeuvre. Resource constraints and environmental problems are increasingly pressing. A new crisis will be like a virulent infection attacking a body whose immune system is already compromised.

Economic problems feed social and political discontent, opening the way for extremism. In the Great Depression the fear and disaffection of ordinary people who had lost their jobs and savings gave rise to fascism. Writing of the period, historian A.J.P. Taylor noted:

“[the] middle class, everywhere the pillar of stability and respectability ... was now utterly destroyed ... they became resentful ... violent and irresponsible ... ready to follow the first demagogic saviour ...”

In 130 AD, Claudius Ptolemaeus, known as Ptolemy, a mathematician, astronomer, geographer and astrologer, developed an astronomical system. The system fitted the accepted view of philosophers and the church that the earth was at the centre of the universe and all stellar bodies moved with perfect uniform circular motion. When Galileo observed the actual movements of heavenly objects and tested Ptolemy’s theories against the evidence, the system collapsed. Economic and political processes increasingly resemble the Ptolemaic system where the possibility of lower growth, reduced wealth, reduced living standards, and constrained economic sovereignty do not feature in the policy debate.

The world generally and financial investors are remarkably unprepared for the events that are unfolding. Humanity faces this, its greatest crisis, with, in the words of Biologist E.O. Wilson, “Palaeolithic emotions”, “medieval institutions” and delusions about its “god-like technology”. Like Fitzgerald’s tragic hero Gatsby, the battle cry is: “Can’t repeat the past? Why of course you can!”

Satyajit Das is a former banker and now a world-renowned author and consultant. His latest book is A Banquet of Consequences. © 2015 Satyajit Das, All Rights reserved.