There has been a constant stream of articles recently highlighting potentially weak lending practices. Sectors highlighted include US high yield bonds and leveraged loans, European and Japanese sovereign debt, European and Chinese banks, emerging market bonds, margin loans, subprime auto loans, student loans and Chinese shadow banking. In isolation these can seem like small problems, but is there a wider issue at play that could drive investment returns in the coming years? This article discusses the findings from three recent seminal papers (all linked below) which highlight the growing global misuse of debt. It also considers the consequences for future investment returns and economic growth.

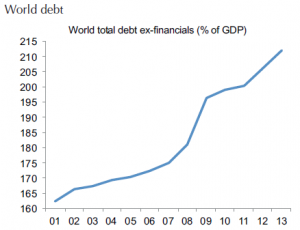

As shown in the graph below, the thesis that the world has been going through a period of debt reduction following the financial crisis is completely false. The low levels of GDP growth aren’t explained by debt levels falling, rather, low levels of growth have occurred despite a substantial increase in debt outstanding. This expansion in debt levels is consistent across developed and emerging economies.

The Geneva Report breaks down total debt to GDP ratios into households, businesses, financials and governments. Japan, Greece, Italy, Portugal and Ireland have very high levels of government debt. Belgium, Sweden and Spain standout for their high levels of business debt. The Netherlands, Australia and Ireland have high levels of household debt. If a bout of global debt reduction was to occur, this data points to very different sectorial impacts for each country.

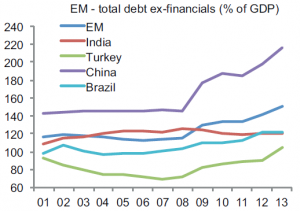

In emerging markets, Hungary, India and Brazil are carrying the highest levels of government debt. China, Hungary and Thailand have the largest exposures from the private (businesses and households) sector. The most interesting story in the last five years is about China.

The Report also shows which countries are the most indebted to other countries (external debt). Portugal, Greece, Ireland, Spain and Australia ranked highest on this measure amongst developed countries. Hungary, Poland, Turkey and Czech Republic are highest in emerging markets. In crises in South America and Asia in the last 40 years, a key trigger has been overseas investors losing confidence and withdrawing their capital. If the external debt hasn’t been productively invested with ongoing profits available to service the debt, countries run the risk of seeing large amounts of capital withdrawn from their economies. This withdrawal of capital almost certainly results in a period of recession.

The Geneva Report raises many questions. If there hadn’t been growth in debt levels since 2008 how much worse would the financial crisis have been? If China hadn’t gone on an enormous debt binge, would its GDP growth rates have collapsed? If there is another financial crisis, which governments would have no ability to issue more debt to fund spending in an attempt to offset a pullback in private sector spending? Is it possible that investors could suffer indigestion after gorging on debt for so many years? There are no easy answers, but these questions all point to the possibility that a future which includes global debt reductions might look more like the great depression than the great recession.

The Great Mortgaging: housing finance, crises, and business cycles (San Francisco Fed)

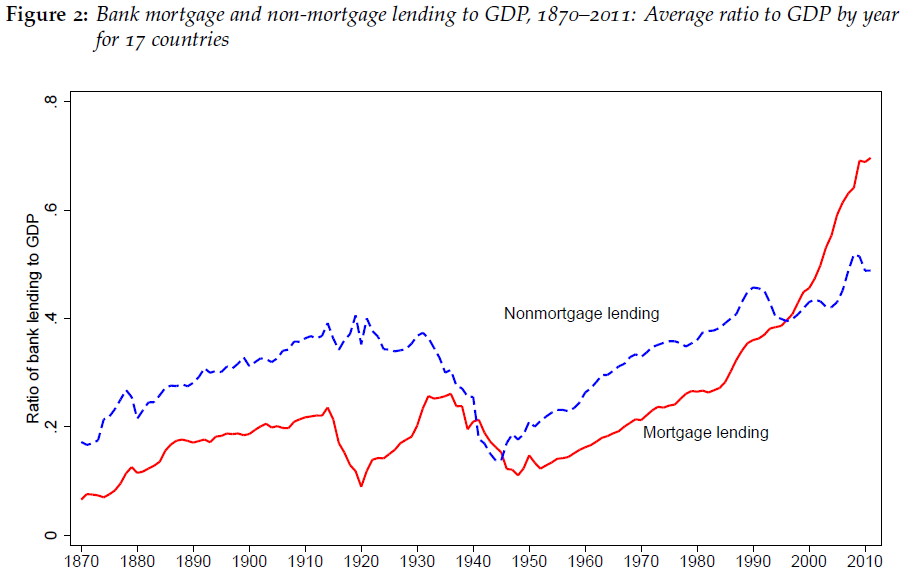

Traditional economic theory has households as net savers, businesses as net borrowers and banks as intermediaries between the two groups. The result is that households earn a return on their excess savings and businesses borrow and invest which increases economic output and employment. This paper puts aside the traditional view of how credit operates showing that (1) banks are becoming an ever larger part of the economy (financialisation) and (2) their lending is increasingly skewed towards property based (mortgage) lending. The chart below illustrates both these conclusions.

Growth in credit by banks over the 50 year period from 1960 to 2010 was disproportionately to households for mortgage activities. Spain, Denmark, Australia and Great Britain are standouts. Spain, Denmark and Great Britain saw a material downward movement in their house prices following the onset of the financial crisis, but not in Australia.

Lastly, the authors found that recessions with a financial crisis were deeper and longer lasting than those without. They split the data into mortgage and non-mortgage financial crises and found that recessions with a mortgage (property) bust were much deeper than recessions with a non-mortgage credit bust.

It would be easy to write-off the European Bank Stress Test as more of a tickle test than a stress test but there are still some worthwhile outcomes. Firstly, the exercise provided a largely standardised application of regulatory rules, which helps analysts substantially as there is a fairer way to compare banks within the Eurozone.

Secondly, some of the skeletons have been brought out of the closet with the results highlighting banks that have been gaming the rules and pretending that certain losses haven’t really occurred. The main report shows two grey shaded columns on pages 41 to 45 that give a reasonable guide to who is cooking the books. These grey columns have negative common equity tier one (CET1) ratios for two banks in Cyprus, three in Greece, two in Ireland, two in Italy and one in Portugal after applying the regulator’s scenario and correcting some of the disguised losses.

The list of shortcomings is long but the major items are:

- The scenarios for unemployment increasing and GDP decreasing are far milder than what has been seen in some of the European countries since the onset of the financial crisis.

- Banks that are currently under restructuring plans were given substantial credit for what they said they are going to do before they’ve actually done it.

- Transitional arrangements on goodwill, deferred tax assets, defined benefit pension plan shortfalls and provision shortfalls were allowed, which disguise how bad things really are.

The two previous rounds of stress testing gave a pass mark to Irish banks and Dexia, who subsequently required bailouts within 12 months after the results were published. This round has done a better job of identifying the weakest links in the European banking system, particularly those banks which haven’t cleared the problems from the last financial crisis. However, it provides little confidence that European banks are well placed to deal with another financial crisis.

Conclusions from these three papers

The papers together highlight the increasing global dependence on the growth in debt levels to fuel economic growth. Finance has been an ever-greater part of developed and emerging market economies such that ordinary people are increasingly impacted (both income and wealth effects) by the ups and downs in credit availability through the cycle. Credit is increasingly being used for property, consumer and speculative investment activities rather than growth-generating activities such as productive business investment and necessary infrastructure development.

Low central bank interest rates have predominantly led to speculative lending and investment rather than delivering the desired lift in growth rates or inflation rates. Those who have in the past laughed at the suggestion that Europe or the US could become the next Japan have now stopped laughing with low interest rates increasingly being seen as part of the long term landscape. China is also showing signs of buckling under its rapidly-increasing debt load.

For investors, it’s a good time to reflect on the ability of every asset in their portfolio to withstand a major global economic shock. By and large, asset prices are high and there are many buyers for almost any security with good yield or even the prospect of a decent yield in the future. For credit investments, it’s time to decrease credit risk and credit duration, and to increase structural protections. Most investors are currently doing the opposite of these things, as they see the drop in yield to potentially sub-inflation levels as unacceptable even if it is only temporary. For the contrarians among us, therein lies the opportunity to be positioned with cash available, waiting for some of the high risk investments to inevitably unravel in the medium term.

Jonathan Rochford is Portfolio Manager at Narrow Road Capital. This article has been prepared for educational purposes and is not meant as a substitute for professional and tailored financial advice. Narrow Road Capital advises on and invests in a wide range of securities.